A number of reforms that would improve the estimates of the costs and benefits of transportation projects.

By Robert Krol

Each year, state and local governments decide on which transportation infrastructure projects to build. Often, priority goes to projects directed at reducing highway congestion or air pollution.

The economic backbone of the decision process is supposed to be an objective cost-benefit analysis. However, calculating the costs and benefits of any major project is technically difficult.

- Cost estimates require a determination of labor and material quantities and prices.

- Benefit estimates require forecasting economic growth, demographic trends, and travel patterns in the region.

Clouding the analysis is the fact that this decision process takes place in a political environment. Politicians love the publicity they get at the opening of a high-occupancy vehicle lane or the expansion of a mass transit system. To voters, it may look as if their elected officials are doing something about a region’s transportation problems. More often than not, however, the projects do little to mitigate transportation-related problems.

When it comes to estimating the costs and benefits of proposed projects, this environment creates incentives to cook the books. Because elected officials benefit from these projects, the incentive is to place pressure on analysts to underestimate costs and overestimate benefits so that the projects can move ahead.

Academic researchers have examined the track record of cost-benefit estimates of past transportation infrastructure projects. Bent Flyvbjerg, Mette Skamris Holm, and Søren Buhl, all affiliated with Aalborg University in Denmark, looked at the cost estimates for 258 transportation projects valued at $90 billion built in countries around the world during the 20th century.

Academic researchers have examined the track record of cost-benefit estimates of past transportation infrastructure projects. Bent Flyvbjerg, Mette Skamris Holm, and Søren Buhl, all affiliated with Aalborg University in Denmark, looked at the cost estimates for 258 transportation projects valued at $90 billion built in countries around the world during the 20th century.

They found large cost overruns to be common, with an average overrun of almost 28 percent. Rail projects experienced the largest average cost overrun, at nearly 45 percent.

There is no evidence that transportation planners learned from their mistakes, as the size of the errors did not decline over time. This persistence suggests the errors are systematic, rather than random errors generated by unexpected shocks to the economy following the forecast.

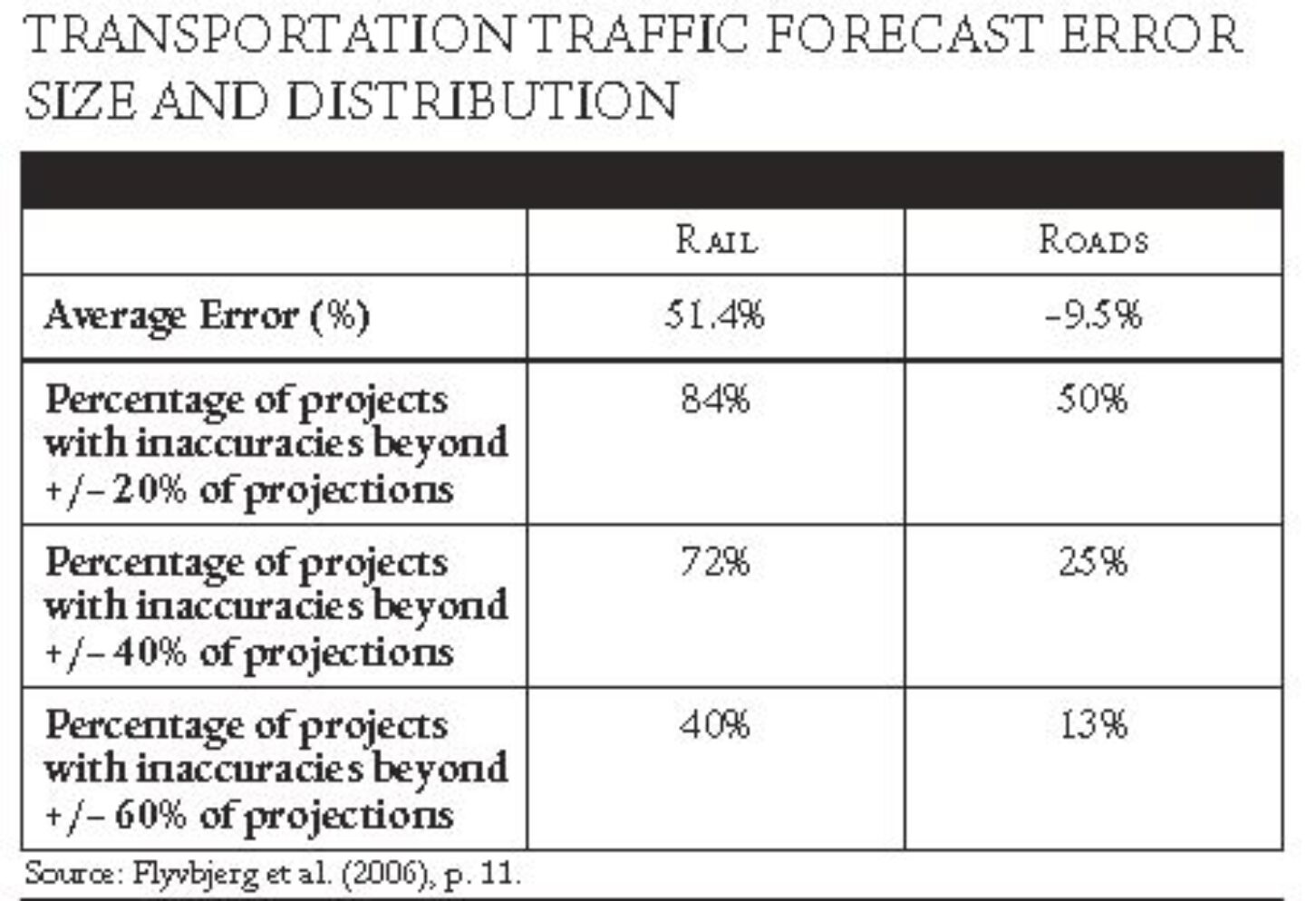

In another paper, the same researchers looked at the accuracy of passenger and traffic flow forecasts for 210 rail and road infrastructure projects using data from 14 countries. Those projects were worth $58 billion and constructed between 1969 and 1998.

Comparing actual vehicle or passenger flows in the projects’ first year of operation to forecasted flows, the authors find transportation planners overestimated passenger flow for railroads and underestimated vehicle flow for roads.

For rail projects, passenger flows were overestimated by more than 50 percent. Nearly 85 percent of rail projects overestimated passenger flows by more than 20 percent, 40 percent of the errors exceeded 60 percent.

For rail projects, passenger flows were overestimated by more than 50 percent. Nearly 85 percent of rail projects overestimated passenger flows by more than 20 percent, 40 percent of the errors exceeded 60 percent.

Because policymakers favor mass transit, we’d expect the political pressure to be reversed when it comes to estimating the benefits of additional roads. The findings suggest this may be the case, as the researchers found that road traffic flows (the forecast of benefits) were underestimated by about 10 percent.

Such errors do not only plague public projects; overestimating benefits also occurs in privately financed toll roads, tunnels, and bridges. Transportation finance researcher Robert Bain examined the record for 100 private projects built worldwide between 2002 and 2005. He found the average forecast overestimated traffic flows by 23 percent.

We would think that private investors, risking their own funds, would produce a more unbiased forecast. While the errors are somewhat smaller, the results suggest that private promoters also provide overly optimistic projections of traffic demand, perhaps as a way to improve access to capital.

Government analysts and consultants conducting the cost-benefit analyses are under pressure to bias the projections in a way that favors the goals of the officials who employ the analysts.

If widening a bridge will garner enough additional votes to win the next election, a politician may apply pressure to ensure that cost and benefit estimates place the project in the best light. A consultant’s future project opportunities or the salary of a staff analyst likely depends on how willing he or she is to play along.

While reputation serves as a constraint on how far an analyst would massage a forecast, the evidence from actual projects suggests political forces dominate the decision process. While it is not possible to completely eliminate the political pressure to cook the books, there are a number of reforms that would improve the estimates of the costs and benefits of transportation projects.

First, specialists who are not directly involved in the project should review the analysis. This kind of review process has improved forecasts made by the Congressional Budget Office.

Second, Flyvbjerg suggests comparing the cost and benefit estimates of proposed projects to those of completed projects with similar characteristics. If there are enough comparable projects, past outcomes can put a lid on overzealous estimates of benefits and underestimates of cost. Transparency is important. Making the results of these comparisons public would allow taxpayers to judge the viability of a given project.

Third, cost and benefit estimates should be made using a range of economic assumptions. For example, what would happen to rail ridership if the economy grew 1 percent slower? How robust are the estimates?

Finally, the salary of the analyst or consultant could be tied to the accuracy of an estimate. This would counteract political pressures to bias transportation project forecasts.

Taxpayers and investors need to be careful when it comes to projections of the costs and benefits of transportation infrastructure projects. They are likely to be biased to favor projects politicians want. This bias should give pause to any supporter of high-speed rail or any public megaproject in the United States or abroad.

A finding that the biases are large but, once built, the projects still produce a (small) net benefit does not mean there is no reason for concern. There are opportunity costs associated with low-return projects. Alternative non-transportation projects or tax cuts would have made taxpayers better off.

Flyvbjerg and his coauthors conclude that politicians sell the projections as scientific, but they turn out to be “strategic misrepresentations” that end up being financial disasters that often provide negative net returns.

Robert Krol is professor of economics at California State University, Northridge. This commentary appeared in the Winter 2015-2016 issue of Regulation, the Cato Review of Business and Government, and is reprinted by the Georgia Public Policy Foundation with permission.

By Robert Krol

Each year, state and local governments decide on which transportation infrastructure projects to build. Often, priority goes to projects directed at reducing highway congestion or air pollution.

The economic backbone of the decision process is supposed to be an objective cost-benefit analysis. However, calculating the costs and benefits of any major project is technically difficult.

- Cost estimates require a determination of labor and material quantities and prices.

- Benefit estimates require forecasting economic growth, demographic trends, and travel patterns in the region.

Clouding the analysis is the fact that this decision process takes place in a political environment. Politicians love the publicity they get at the opening of a high-occupancy vehicle lane or the expansion of a mass transit system. To voters, it may look as if their elected officials are doing something about a region’s transportation problems. More often than not, however, the projects do little to mitigate transportation-related problems.

When it comes to estimating the costs and benefits of proposed projects, this environment creates incentives to cook the books. Because elected officials benefit from these projects, the incentive is to place pressure on analysts to underestimate costs and overestimate benefits so that the projects can move ahead.

Academic researchers have examined the track record of cost-benefit estimates of past transportation infrastructure projects. Bent Flyvbjerg, Mette Skamris Holm, and Søren Buhl, all affiliated with Aalborg University in Denmark, looked at the cost estimates for 258 transportation projects valued at $90 billion built in countries around the world during the 20th century.

Academic researchers have examined the track record of cost-benefit estimates of past transportation infrastructure projects. Bent Flyvbjerg, Mette Skamris Holm, and Søren Buhl, all affiliated with Aalborg University in Denmark, looked at the cost estimates for 258 transportation projects valued at $90 billion built in countries around the world during the 20th century.

They found large cost overruns to be common, with an average overrun of almost 28 percent. Rail projects experienced the largest average cost overrun, at nearly 45 percent.

There is no evidence that transportation planners learned from their mistakes, as the size of the errors did not decline over time. This persistence suggests the errors are systematic, rather than random errors generated by unexpected shocks to the economy following the forecast.

In another paper, the same researchers looked at the accuracy of passenger and traffic flow forecasts for 210 rail and road infrastructure projects using data from 14 countries. Those projects were worth $58 billion and constructed between 1969 and 1998.

Comparing actual vehicle or passenger flows in the projects’ first year of operation to forecasted flows, the authors find transportation planners overestimated passenger flow for railroads and underestimated vehicle flow for roads.

For rail projects, passenger flows were overestimated by more than 50 percent. Nearly 85 percent of rail projects overestimated passenger flows by more than 20 percent, 40 percent of the errors exceeded 60 percent.

For rail projects, passenger flows were overestimated by more than 50 percent. Nearly 85 percent of rail projects overestimated passenger flows by more than 20 percent, 40 percent of the errors exceeded 60 percent.

Because policymakers favor mass transit, we’d expect the political pressure to be reversed when it comes to estimating the benefits of additional roads. The findings suggest this may be the case, as the researchers found that road traffic flows (the forecast of benefits) were underestimated by about 10 percent.

Such errors do not only plague public projects; overestimating benefits also occurs in privately financed toll roads, tunnels, and bridges. Transportation finance researcher Robert Bain examined the record for 100 private projects built worldwide between 2002 and 2005. He found the average forecast overestimated traffic flows by 23 percent.

We would think that private investors, risking their own funds, would produce a more unbiased forecast. While the errors are somewhat smaller, the results suggest that private promoters also provide overly optimistic projections of traffic demand, perhaps as a way to improve access to capital.

Government analysts and consultants conducting the cost-benefit analyses are under pressure to bias the projections in a way that favors the goals of the officials who employ the analysts.

If widening a bridge will garner enough additional votes to win the next election, a politician may apply pressure to ensure that cost and benefit estimates place the project in the best light. A consultant’s future project opportunities or the salary of a staff analyst likely depends on how willing he or she is to play along.

While reputation serves as a constraint on how far an analyst would massage a forecast, the evidence from actual projects suggests political forces dominate the decision process. While it is not possible to completely eliminate the political pressure to cook the books, there are a number of reforms that would improve the estimates of the costs and benefits of transportation projects.

First, specialists who are not directly involved in the project should review the analysis. This kind of review process has improved forecasts made by the Congressional Budget Office.

Second, Flyvbjerg suggests comparing the cost and benefit estimates of proposed projects to those of completed projects with similar characteristics. If there are enough comparable projects, past outcomes can put a lid on overzealous estimates of benefits and underestimates of cost. Transparency is important. Making the results of these comparisons public would allow taxpayers to judge the viability of a given project.

Third, cost and benefit estimates should be made using a range of economic assumptions. For example, what would happen to rail ridership if the economy grew 1 percent slower? How robust are the estimates?

Finally, the salary of the analyst or consultant could be tied to the accuracy of an estimate. This would counteract political pressures to bias transportation project forecasts.

Taxpayers and investors need to be careful when it comes to projections of the costs and benefits of transportation infrastructure projects. They are likely to be biased to favor projects politicians want. This bias should give pause to any supporter of high-speed rail or any public megaproject in the United States or abroad.

A finding that the biases are large but, once built, the projects still produce a (small) net benefit does not mean there is no reason for concern. There are opportunity costs associated with low-return projects. Alternative non-transportation projects or tax cuts would have made taxpayers better off.

Flyvbjerg and his coauthors conclude that politicians sell the projections as scientific, but they turn out to be “strategic misrepresentations” that end up being financial disasters that often provide negative net returns.

Robert Krol is professor of economics at California State University, Northridge. This commentary appeared in the Winter 2015-2016 issue of Regulation, the Cato Review of Business and Government, and is reprinted by the Georgia Public Policy Foundation with permission.