If Trump keeps his promise to devolve education, all eyes move to the states.

By Jenn Hatfield

When President Donald Trump was sworn into office on January 20, the clock started ticking on the 282 promises he made on the campaign trail.

While his every move has garnered significant media attention, Trump has also pledged to make what happens in Washington matter less. In his inaugural address, he declared, “We are transferring power from Washington, D.C. and giving it back to you, the American People.”

So it’s only fitting to give a bit more attention to what governors are saying – especially on K-12 education, where Trump and Secretary of Education have both promised to respect state autonomy and make good on the states-rights spirit of the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA).

So it’s only fitting to give a bit more attention to what governors are saying – especially on K-12 education, where Trump and Secretary of Education have both promised to respect state autonomy and make good on the states-rights spirit of the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA).

As a first step in doing that, I read transcripts of 39 governors’ 2017 “State of the State” addresses. Some commonalities are unsurprising. For example, 25 governors mentioned higher education, with their promises ranging from tuition-free public college to a Borrower’s Bill of Rights for student loans. Twenty mentioned vocational education, 19 mentioned educational inequity, 18 mentioned educational technology or innovation, and 16 mentioned early education.

Graduation rates also weighed heavily on governors’ minds, with a dozen touting or lamenting their states’ progress in their speeches. Graduation rates have been criticized for being easy to inflate, and while it’s true that they are not a perfect signal of college or workforce readiness, they are also often a minimum qualification for admission or employability.

In evaluating governors’ remarks on graduation rates, it’s worth keeping this distinction in mind and considering whether their strategies for improvement will go hand-in-hand with improving preparedness for life after high school.

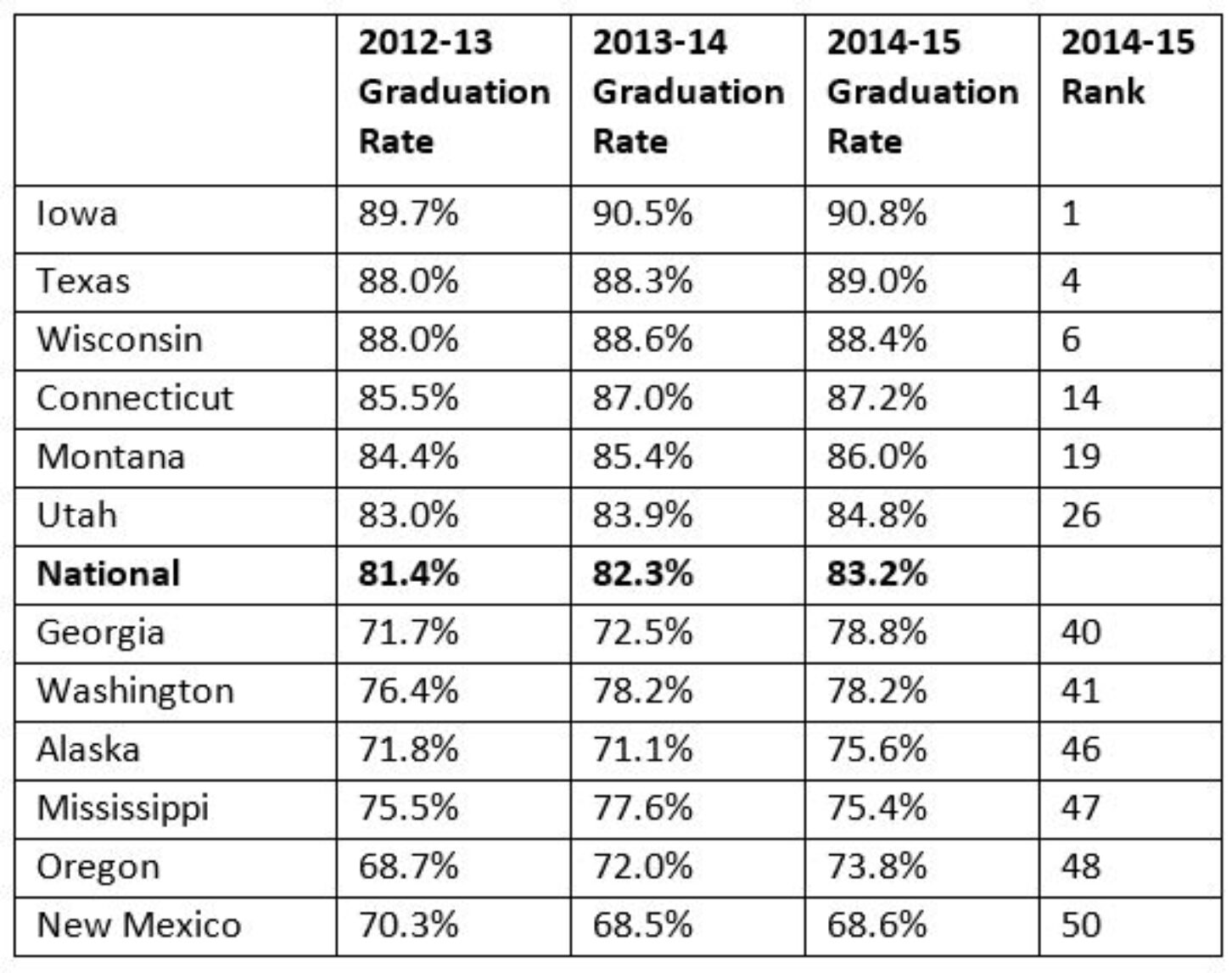

The table lists the graduation rates for the past three years in which national data was available, for the states whose governors mentioned graduation rates in their 2017 speeches. The states are ranked from 1 to 51, where a ranking of 1 signifies the top graduation rate of any state (and Washington, D.C.) in 2014-15.

Over this three-year span, the national graduation rate increased by 1.8 percentage points, and the vast majority of states increased their rates as well. All but 10 states, and all but two states in the table above, increased their graduation rates from 2012-13 to 2014-15.

Notably, the governors who mentioned graduation rates in their speeches largely represented states at either end of the performance spectrum. Half of the governors were from states whose 2014-15 graduation rates ranked in the bottom 20 percent nationwide, while another quarter were from states ranked in the top 20 percent.

Georgia’s Gov. Nathan Deal also laid out a plan, aimed at reducing the number of chronically failing schools in the state:

[Georgia] will place an emphasis on elementary schools. If we can reverse this alarming trend early on, if we can eliminate this negative that directly or indirectly impacts all of us, then our reading comprehension scores, math skills, graduation rates and the quality of our workforce will all improve considerably. To that end, my office is working closely with Lt. Gov. Cagle, Speaker Ralston, House Chairman Brooks Coleman, Rep. Kevin Tanner, Senate Chairman Lindsey Tippins, Sen. Freddie Powell Sims and others to craft legislation that will be presented to you this session.

On January 20, Trump opened his presidency by announcing, “We, the citizens of America, are now joined in a great national effort.” He promised, “We will face challenges. We will confront hardships. But we will get the job done. … Everyone is listening to you now.”

Trump was referring to rebuilding the American dream for citizens who have lost hope. But looking at the words from our nation’s governors, his words could’ve just as easily applied to graduation rates.

States are facing challenges, making progress, creating new promises – and, with any luck, they too will get the job done in preparing students for the future. With ESSA and other devolutions of federal power over education, everyone is watching them now.

This commentary is excerpted from an article by Jenn Hatfield, a research associate in Education Policy Studies at the American Enterprise Institute, and is reprinted by the Georgia Public Policy Foundation with permission. Access the complete article here. The Foundation is an independent think tank that proposes market-oriented approaches to public policy to improve the lives of Georgians. Nothing written here is to be construed as necessarily reflecting the view of the Georgia Public Policy Foundation or as an attempt to aid or hinder the passage of any bill before the U.S. Congress or the Georgia Legislature.

© Georgia Public Policy Foundation (February 10, 2017). Permission to reprint in whole or in part is hereby granted, provided the author and her affiliations are cited.

By Jenn Hatfield

When President Donald Trump was sworn into office on January 20, the clock started ticking on the 282 promises he made on the campaign trail.

While his every move has garnered significant media attention, Trump has also pledged to make what happens in Washington matter less. In his inaugural address, he declared, “We are transferring power from Washington, D.C. and giving it back to you, the American People.”

So it’s only fitting to give a bit more attention to what governors are saying – especially on K-12 education, where Trump and Secretary of Education have both promised to respect state autonomy and make good on the states-rights spirit of the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA).

So it’s only fitting to give a bit more attention to what governors are saying – especially on K-12 education, where Trump and Secretary of Education have both promised to respect state autonomy and make good on the states-rights spirit of the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA).

As a first step in doing that, I read transcripts of 39 governors’ 2017 “State of the State” addresses. Some commonalities are unsurprising. For example, 25 governors mentioned higher education, with their promises ranging from tuition-free public college to a Borrower’s Bill of Rights for student loans. Twenty mentioned vocational education, 19 mentioned educational inequity, 18 mentioned educational technology or innovation, and 16 mentioned early education.

Graduation rates also weighed heavily on governors’ minds, with a dozen touting or lamenting their states’ progress in their speeches. Graduation rates have been criticized for being easy to inflate, and while it’s true that they are not a perfect signal of college or workforce readiness, they are also often a minimum qualification for admission or employability.

In evaluating governors’ remarks on graduation rates, it’s worth keeping this distinction in mind and considering whether their strategies for improvement will go hand-in-hand with improving preparedness for life after high school.

The table lists the graduation rates for the past three years in which national data was available, for the states whose governors mentioned graduation rates in their 2017 speeches. The states are ranked from 1 to 51, where a ranking of 1 signifies the top graduation rate of any state (and Washington, D.C.) in 2014-15.

Over this three-year span, the national graduation rate increased by 1.8 percentage points, and the vast majority of states increased their rates as well. All but 10 states, and all but two states in the table above, increased their graduation rates from 2012-13 to 2014-15.

Notably, the governors who mentioned graduation rates in their speeches largely represented states at either end of the performance spectrum. Half of the governors were from states whose 2014-15 graduation rates ranked in the bottom 20 percent nationwide, while another quarter were from states ranked in the top 20 percent.

Georgia’s Gov. Nathan Deal also laid out a plan, aimed at reducing the number of chronically failing schools in the state:

[Georgia] will place an emphasis on elementary schools. If we can reverse this alarming trend early on, if we can eliminate this negative that directly or indirectly impacts all of us, then our reading comprehension scores, math skills, graduation rates and the quality of our workforce will all improve considerably. To that end, my office is working closely with Lt. Gov. Cagle, Speaker Ralston, House Chairman Brooks Coleman, Rep. Kevin Tanner, Senate Chairman Lindsey Tippins, Sen. Freddie Powell Sims and others to craft legislation that will be presented to you this session.

On January 20, Trump opened his presidency by announcing, “We, the citizens of America, are now joined in a great national effort.” He promised, “We will face challenges. We will confront hardships. But we will get the job done. … Everyone is listening to you now.”

Trump was referring to rebuilding the American dream for citizens who have lost hope. But looking at the words from our nation’s governors, his words could’ve just as easily applied to graduation rates.

States are facing challenges, making progress, creating new promises – and, with any luck, they too will get the job done in preparing students for the future. With ESSA and other devolutions of federal power over education, everyone is watching them now.

This commentary is excerpted from an article by Jenn Hatfield, a research associate in Education Policy Studies at the American Enterprise Institute, and is reprinted by the Georgia Public Policy Foundation with permission. Access the complete article here. The Foundation is an independent think tank that proposes market-oriented approaches to public policy to improve the lives of Georgians. Nothing written here is to be construed as necessarily reflecting the view of the Georgia Public Policy Foundation or as an attempt to aid or hinder the passage of any bill before the U.S. Congress or the Georgia Legislature.

© Georgia Public Policy Foundation (February 10, 2017). Permission to reprint in whole or in part is hereby granted, provided the author and her affiliations are cited.