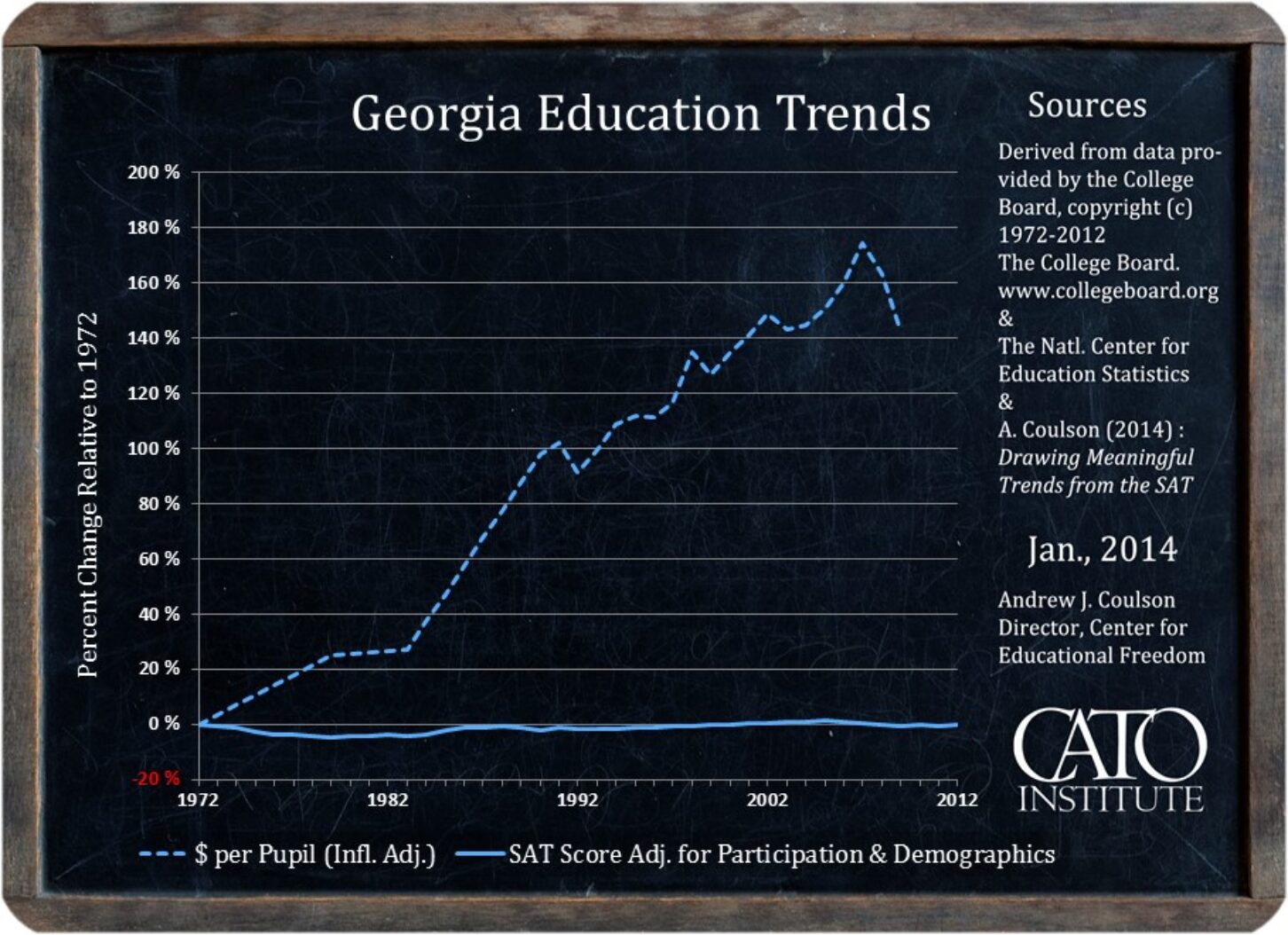

New data demonstrates that there is no link between state education spending and student outcomes, says Andrew Coulson, director of the Cato Institute’s Center for Educational Freedom.

Comparing academic performance with state spending is an incredibly valuable way to measure the efficacy of education policies. Looking at academic performance on a national scale, the results are not good. Seventeen year olds’ performance has been stagnant since 1970 across all subjects, despite K-12 education costs tripling.

Unfortunately, similar data at the state level has been very difficult to come by. Spending data exists for the last 50 years, but it is scattered across various publications. Academic data, on the other hand, is even more difficult to find, as it is either unavailable prior to 1990 or involves an unrepresentative sample.

To produce the type of data needed to evaluate education policies effectively, Coulson took state SAT score averages and adjusted them by participation rate and student demographics (factors known to affect outcomes). He then compared the results with recent state-level National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) scores, producing SAT score trends from 1972 to present day.

What did he find?

- For all 50 states, the correlation between spending and academic performance was 0.075. Correlations are measured on a scale that reaches from 0 to 1 — anything below 0.3 or 0.4 is considered a very weak correlation, and the closer the figure is to 1, the higher the correlation.

- A correlation of 0.075 suggests that there is absolutely no link between education spending and student performance at the end of high school. While spending has exploded, performance has stagnated or simply declined.

- And the states that did see substantial spending declines over certain periods saw no declines in SAT scores.

In short — academic performance and test scores across the 50 states appear to have no connection whatsoever with the amount of state education funding.

In nearly every other field in the United States, productivity has risen between 1970 and present day, especially as a result of new technologies. It is time to ask what in our approach to education is preventing it from demonstrating a similar level of success and growth.

Source: Andrew J. Coulson, “State Education Trends,” Cato Institute, March 18, 2014.

New data demonstrates that there is no link between state education spending and student outcomes, says Andrew Coulson, director of the Cato Institute’s Center for Educational Freedom.

Comparing academic performance with state spending is an incredibly valuable way to measure the efficacy of education policies. Looking at academic performance on a national scale, the results are not good. Seventeen year olds’ performance has been stagnant since 1970 across all subjects, despite K-12 education costs tripling.

Unfortunately, similar data at the state level has been very difficult to come by. Spending data exists for the last 50 years, but it is scattered across various publications. Academic data, on the other hand, is even more difficult to find, as it is either unavailable prior to 1990 or involves an unrepresentative sample.

To produce the type of data needed to evaluate education policies effectively, Coulson took state SAT score averages and adjusted them by participation rate and student demographics (factors known to affect outcomes). He then compared the results with recent state-level National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) scores, producing SAT score trends from 1972 to present day.

What did he find?

- For all 50 states, the correlation between spending and academic performance was 0.075. Correlations are measured on a scale that reaches from 0 to 1 — anything below 0.3 or 0.4 is considered a very weak correlation, and the closer the figure is to 1, the higher the correlation.

- A correlation of 0.075 suggests that there is absolutely no link between education spending and student performance at the end of high school. While spending has exploded, performance has stagnated or simply declined.

- And the states that did see substantial spending declines over certain periods saw no declines in SAT scores.

In short — academic performance and test scores across the 50 states appear to have no connection whatsoever with the amount of state education funding.

In nearly every other field in the United States, productivity has risen between 1970 and present day, especially as a result of new technologies. It is time to ask what in our approach to education is preventing it from demonstrating a similar level of success and growth.

Source: Andrew J. Coulson, “State Education Trends,” Cato Institute, March 18, 2014.