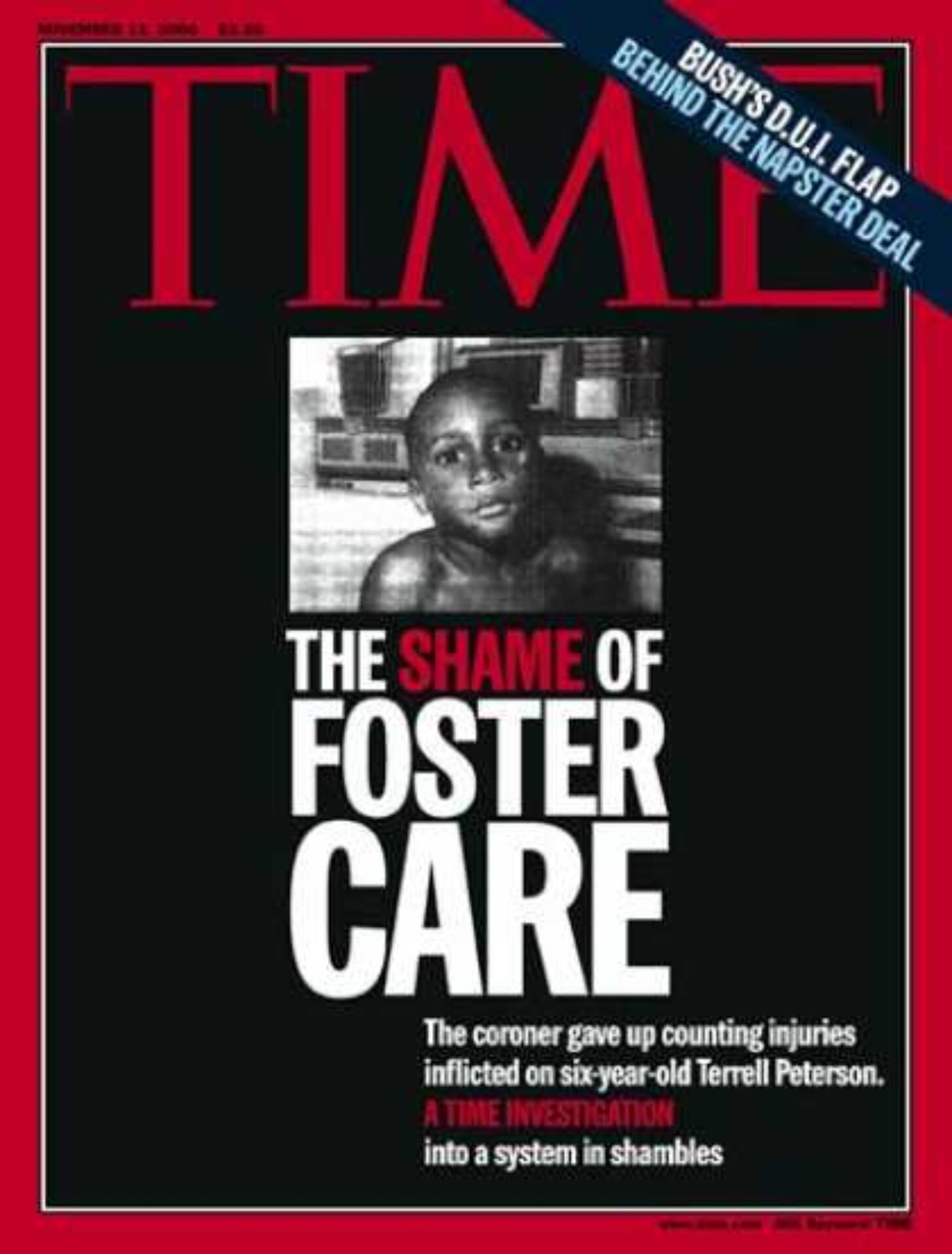

Look at the little boy whose picture is on TIME magazine. Sixteen years ago five-year-old Terrell Peterson was murdered by his grandmother and aunt. Rather than love and care for the boy they killed him. Now look at the photo of the happy little girl. Last fall ten-year-old Emani Moss’s emaciated and burned body was found in a Gwinnett County dumpster after she was allegedly murdered by her father and stepmother. Rather than love and care for Emani prosecutors say they killed her.

Terrell and Emani experienced unspeakable horror before death. Their cases share another common factor. In both cases state child protective services officials had been warned, failed to take action and even started a cover-up after Terrell’s death. Good work has been done in state child protective services over the past fifteen years but Georgia cannot escape the image of what happened to Peterson in January 1998 and now Moss in October last year. Last fall a Paulding County boy was allegedly killed by his father, again, a case that also was under state jurisdiction.

Headlines about family-based child murders are nightmarish for protective services agencies and for politicians who are sworn to safeguard children. Georgia child welfare workers interact with tens of thousands of children and families each year. Hundreds of thousands, even millions of decisions are made about the best interests of children. Most decisions never become news.

But it takes just one Terrell Peterson, just one Emani Moss for public scrutiny to judge that an entire child protective services system is off-the-rail and in need of a possible major overhaul. At the very least, it makes sense to take a dispassionate look at protective services and foster care through the eyes of folks who operate inside the conversation but outside state agencies.

Such an initiative convened last week as twenty Child Welfare Reform Council appointees and dozens of advocates packed into a room at the Arthur Blank Family Office in Atlanta to start a review ordered by Governor Nathan Deal. Terrell Peterson’s murder by his grandmother and aunt caused Governor Roy Barnes to create a similar council fourteen years ago.

None of the new appointees are state agency officials. Members include child service and non-profit agency executives, juvenile court judges, state senators and representatives, a former foster care youth, a foster care parent, a detective, a university president and a faith-based community services provider.

Deal told council members the process ahead would “drain your brains.” He compared the child welfare reform initiative to three years of state criminal justice reform and Deal said their recommendations by year-end could lead to 2015 legislation. The council is chaired by child advocate Stephanie Blank who said crimes against children often go unheard and unnoticed, adding, “Many of the voices are not old enough to even speak their pain.”

The council will hold public meetings and will work in committees not yet announced. Outside experts will provide data and counsel. Whether to privatize state foster care services is one but likely not the most high profile agenda item. There will be an intense analysis about how to identify and protect vulnerable children like Terrell Peterson and Emani Moss.

“One big challenge we have in our state is we really don’t know how to deal with chronic families who have chronic abuse and neglect,” said Douglas County Juvenile Court Chief Judge Peggy Walker. “Those children are the ones that are at risk of death but we have a tendency to do the same thing the same way time one, time two and time three.” Walker is a council member.

Child welfare service has lots of moving parts. Here are just a few:

After declining and stabilizing for years, the number of new referrals has substantially increased every month since last September. One reason is Georgia launched a toll free number (855-GA-CHILD) that anyone can use to report suspected child neglect or abuse. “If you build it they will call,” said DFCS Division Director Sharon Hill. Active investigations grew from 4,758 last July to 11,516 in March 2014.

This year Deal announced the state would add 525 new child protective services caseworkers over the next three years, an acknowledgement that the sector is under-resourced. Consider this: the average caseload for children who receive services is 20,000 per quarter, 80,000 per year. Those are actual children in the system; the number of basic reports is much higher.

Two foster care privatization pilot projects will begin in northwest and central-east Georgia. The pilots were ordered by Deal after House and Senate negotiations about foster care privatization collapsed in the Legislature. The Governor’s Office is not certain whether communities have sufficient resources to sustain widespread privatization. “That’s still a question in our mind,” said Policy Director Erin Hames.

Georgia criminal justice reform focused on detention for serious offenders and community program placement for offenders who pose no public safety threat. Child welfare reform goals are similar, that is, how to make certain caseworkers do not miss warning signs that signal real danger for young people like Terrell Peterson and Emani Moss. “Sometimes you do have to throw out old assumptions and look at it with fresh eyes,” said council chair Stephanie Blank.

Additional Resources