Economists generally agree that revenues from this simpler tax structure would grow faster than our current tax system.

By Kelly McCutchen

It may surprise many people that liberals and conservatives can agree on many aspects of tax policy. The Special Council for Tax Reform and Fairness for Georgians highlighted these areas of agreement in its final report to the General Assembly in 2011:

“Economists generally agree that economic growth and development is best served by a tax system that:

- Creates as few distortions in economic decision-making as possible

- Has broad tax bases and low tax rates

- Has few exemptions and special provisions

- Promotes equity through transfers, subsidies and tax credits rather than by having tax rates increase with income

- Taxes consumption rather than income in order to encourage saving and investment

- Keeps tax rates low since taxes reduce the quantity or level of activity of the thing that is taxed.”[1]

What would it look like if Georgia were to simplify its tax code as much as possible while following these sound economic principles?

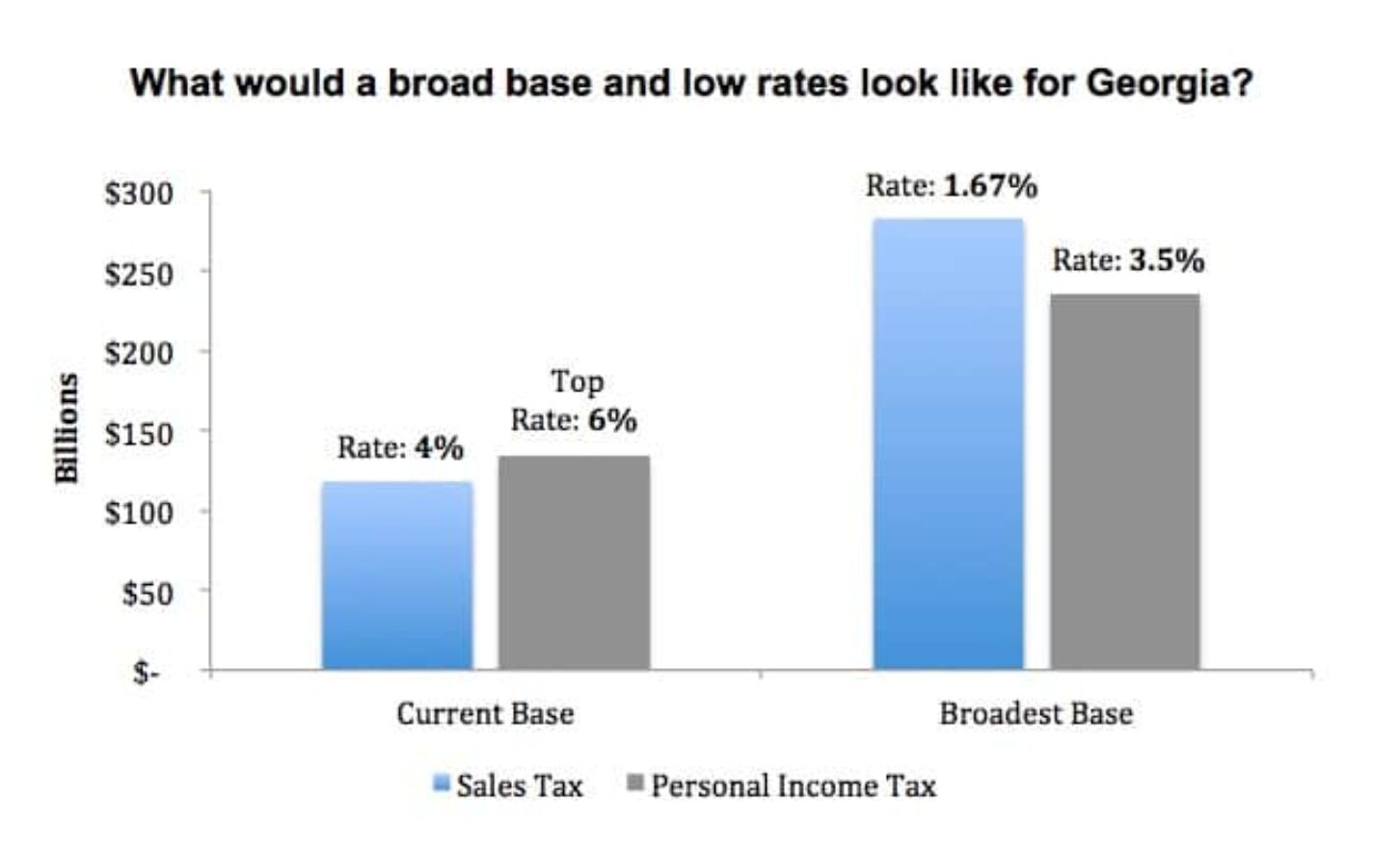

Calculating your personal income tax could be as simple as copying your adjusted gross income from your federal tax return and multiplying by the state tax rate. There would be no deductions or exemptions to calculate, no itemized deductions to keep up with and no marriage penalty. Instead of six different tax brackets and a top rate of 6 percent, a simplified income tax would bring in the same amount of revenue with one rate of about 3.5 percent.

For the sales tax, it would mean taxing the retail sale of all goods and services equally, similar to proposals like the Fair Tax. This would more than double the sales tax base, according to Georgia State University’s Fiscal Research Center. The state sales tax rate could be cut by more than half, from 4 percent to 1.67 percent, and still bring in the same revenue.

Keeping it simple, raising the sales tax rate to 2 percent would allow for an income tax rate of 3 percent.

Even if liberals and conservatives agree to broaden the base and lower rates, two points for debate remain: 1) the amount of tax revenue generated and 2) fairness.

Georgia’s Constitution requires a balanced budget; spending cannot exceed tax revenue. Liberals generally favor more government and conservatives favor a more limited role for government, so liberals tend to see higher tax revenues funding a higher level of government spending, and vice versa for conservatives.

Economists, meanwhile, generally agree that revenues from this simpler tax structure would grow faster than our current tax system.

What about “fairness?” Fairness can have different meanings, but the debate is usually over income. Concerns about the effect of regressive taxes on the poor, the rich not paying their “fair share” and other such arguments fall into this category.

Attempts to resolve fairness concerns are one reason our tax code is so complex. Many of these well-intended policies are inefficient in accomplishing their goals and have been exploited by special interests. A refundable tax credit targeted at the truly poor is preferable to a mishmash of exemptions, deductions or “prebates” for everyone, whether they need them or not.

Congress is currently discussing changes to the Earned Income Tax Credit that could make this approach an effective way to aid the poor and encourage work rather than discourage it. Some states already supplement this credit. It is also a wiser option than raising the minimum wage.

If all this seems too easy, it is. Tax rates will be higher once tax credits for the poor are calculated. Special interests will come out of the woodwork to fight for their deduction or exemption. Politicians, regardless of party or ideology, will resist because a simple tax code reduces influence – and political contributions. There will be winners and losers, and the losers will scream loudly.

Tax reform gets a lot of talk but little action because it is politically so difficult. Incremental reforms are more realistic, among them recently discussed ideas such as limiting itemized deductions and expanding the sales tax base to cover more consumer services, for example.

The timing is good. Proposed transportation tax reforms, as well as other reforms passed by the General Assembly in recent years, have narrowed the sales tax base. These exemptions were all good policy, but in some cases have strained local government finances. Broadening the tax base is a better solution than raising tax rates.

Simplifying our tax code based on sound economic principles would result in more economic growth, more jobs and less time and effort filing taxes. Politically, it’s an incredibly difficult mountain to climb, but the view at the summit is worth the effort.

Sources:

Internal Revenue Service, Tax Statistics, 2012, http://www.irs.gov/uac/SOI-Tax-Stats-Historic-Table-2, Federal AGI for Georgia taxpayers was $235 billion in fiscal year 2012.

“Analysis of Alternative Consumption Tax Structures for Georgia Prepared for the Senate Fair Tax Study Committee,” Georgia State University Fiscal Research Center, September 2013, http://cslf.gsu.edu/files/2014/06/analysis_of_alternative_consumption_tax_structures_for_georgia.pdf Georgia’s sales tax base in fiscal year 2012 was $117.962 billion, a broad tax base would be $282.534 billion, state sales tax revenues used in the calculations were $4.718 billion.

[1] Special Council for Tax Reform and Fairness for Georgians final report, page 10, http://www.terry.uga.edu/media/documents/selig/georgia-tax-reform.pdf

By Kelly McCutchen

It may surprise many people that liberals and conservatives can agree on many aspects of tax policy. The Special Council for Tax Reform and Fairness for Georgians highlighted these areas of agreement in its final report to the General Assembly in 2011:

“Economists generally agree that economic growth and development is best served by a tax system that:

- Creates as few distortions in economic decision-making as possible

- Has broad tax bases and low tax rates

- Has few exemptions and special provisions

- Promotes equity through transfers, subsidies and tax credits rather than by having tax rates increase with income

- Taxes consumption rather than income in order to encourage saving and investment

- Keeps tax rates low since taxes reduce the quantity or level of activity of the thing that is taxed.”[1]

What would it look like if Georgia were to simplify its tax code as much as possible while following these sound economic principles?

Calculating your personal income tax could be as simple as copying your adjusted gross income from your federal tax return and multiplying by the state tax rate. There would be no deductions or exemptions to calculate, no itemized deductions to keep up with and no marriage penalty. Instead of six different tax brackets and a top rate of 6 percent, a simplified income tax would bring in the same amount of revenue with one rate of about 3.5 percent.

For the sales tax, it would mean taxing the retail sale of all goods and services equally, similar to proposals like the Fair Tax. This would more than double the sales tax base, according to Georgia State University’s Fiscal Research Center. The state sales tax rate could be cut by more than half, from 4 percent to 1.67 percent, and still bring in the same revenue.

Keeping it simple, raising the sales tax rate to 2 percent would allow for an income tax rate of 3 percent.

Even if liberals and conservatives agree to broaden the base and lower rates, two points for debate remain: 1) the amount of tax revenue generated and 2) fairness.

Georgia’s Constitution requires a balanced budget; spending cannot exceed tax revenue. Liberals generally favor more government and conservatives favor a more limited role for government, so liberals tend to see higher tax revenues funding a higher level of government spending, and vice versa for conservatives.

Economists, meanwhile, generally agree that revenues from this simpler tax structure would grow faster than our current tax system.

What about “fairness?” Fairness can have different meanings, but the debate is usually over income. Concerns about the effect of regressive taxes on the poor, the rich not paying their “fair share” and other such arguments fall into this category.

Attempts to resolve fairness concerns are one reason our tax code is so complex. Many of these well-intended policies are inefficient in accomplishing their goals and have been exploited by special interests. A refundable tax credit targeted at the truly poor is preferable to a mishmash of exemptions, deductions or “prebates” for everyone, whether they need them or not.

Congress is currently discussing changes to the Earned Income Tax Credit that could make this approach an effective way to aid the poor and encourage work rather than discourage it. Some states already supplement this credit. It is also a wiser option than raising the minimum wage.

If all this seems too easy, it is. Tax rates will be higher once tax credits for the poor are calculated. Special interests will come out of the woodwork to fight for their deduction or exemption. Politicians, regardless of party or ideology, will resist because a simple tax code reduces influence – and political contributions. There will be winners and losers, and the losers will scream loudly.

Tax reform gets a lot of talk but little action because it is politically so difficult. Incremental reforms are more realistic, among them recently discussed ideas such as limiting itemized deductions and expanding the sales tax base to cover more consumer services, for example.

The timing is good. Proposed transportation tax reforms, as well as other reforms passed by the General Assembly in recent years, have narrowed the sales tax base. These exemptions were all good policy, but in some cases have strained local government finances. Broadening the tax base is a better solution than raising tax rates.

Simplifying our tax code based on sound economic principles would result in more economic growth, more jobs and less time and effort filing taxes. Politically, it’s an incredibly difficult mountain to climb, but the view at the summit is worth the effort.

Sources:

Internal Revenue Service, Tax Statistics, 2012, http://www.irs.gov/uac/SOI-Tax-Stats-Historic-Table-2, Federal AGI for Georgia taxpayers was $235 billion in fiscal year 2012.

“Analysis of Alternative Consumption Tax Structures for Georgia Prepared for the Senate Fair Tax Study Committee,” Georgia State University Fiscal Research Center, September 2013, http://cslf.gsu.edu/files/2014/06/analysis_of_alternative_consumption_tax_structures_for_georgia.pdf Georgia’s sales tax base in fiscal year 2012 was $117.962 billion, a broad tax base would be $282.534 billion, state sales tax revenues used in the calculations were $4.718 billion.

[1] Special Council for Tax Reform and Fairness for Georgians final report, page 10, http://www.terry.uga.edu/media/documents/selig/georgia-tax-reform.pdf

Kelly McCutchen is president of the Georgia Public Policy Foundation.