Continuing to resort to 19th-century technology is unwise when a 21st-century generation prefers flexibility and innovative, personalized transit options.

By Benita Dodd

Rail transit as a mass transportation mode is one of the least effective, most expensive options for metro Atlanta, whose reputation as the poster child for sprawl has been earned. The region’s low density makes the mode supremely inefficient and the innovations in transportation make it archaic. Yet rail proponents barely bat an eye at these realities as they continue the campaign to expand MARTA rail.

The Georgia Public Policy Foundation, as it observes the rail discussion, has long held that one of the least objectionable rail corridors would be the Clifton corridor. The corridor is one of the metro area’s most congested commutes, with major employers such as Emory University and Hospital, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Children’s Healthcare at Egleston and the VA Hospital.

That Atlanta has held off rail expansion since 2000 is to its advantage. Unlike Houston, Dallas and other metro areas, instead of relegating commuters to rail, the city can incorporate innovations that are transforming transportation’s future: autonomous vehicles and ride-sharing.

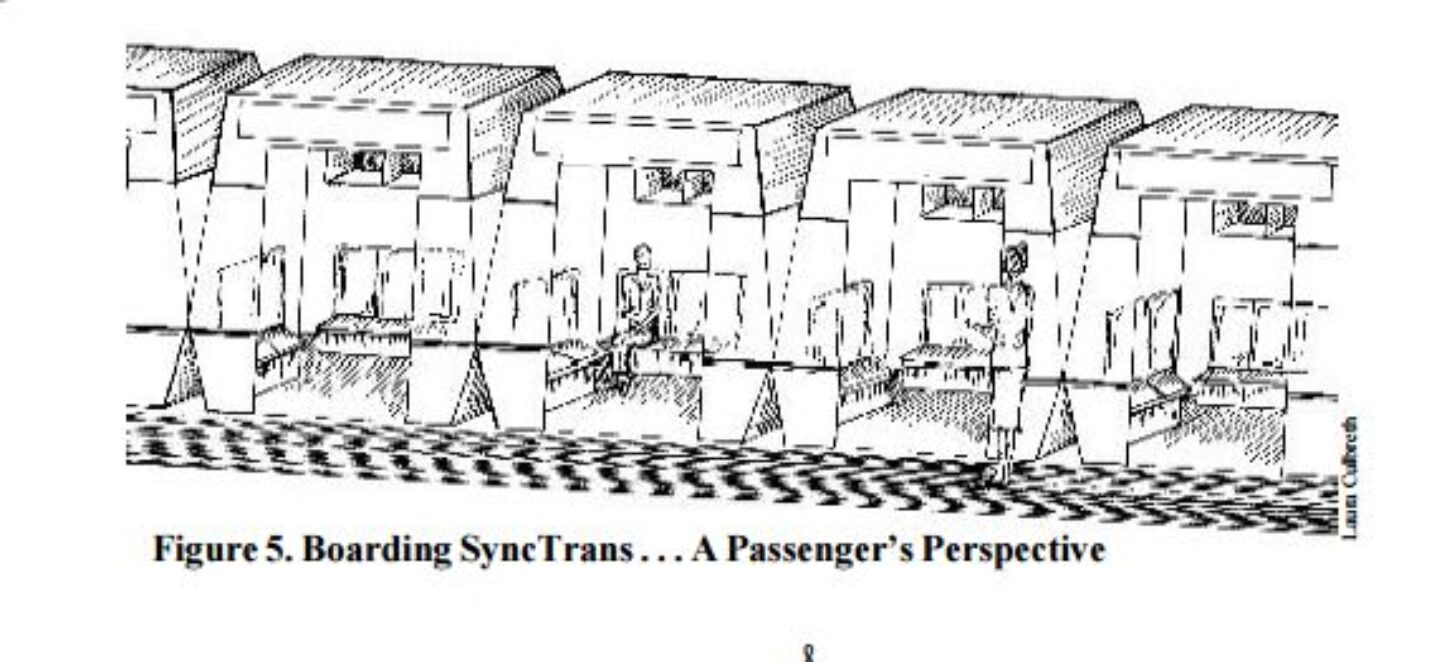

Fifteen years ago, the Foundation published a paper proposing SyncTrans, a system with “small family-sized cars that travel non-stop on an elevated guideway between stations. The quiet, electric-powered system and its cars require no drivers and can operate 24 hours a day, seven days a week. The elevated guideways are cost effective and can be erected quickly. Since the system is fully automated, labor costs are minimal.”

Fifteen years ago, the concept was Disney-Worldish and Jetsonesque. But today, Google cars travel through urban streets and auto manufacturers are uniting behind autonomous vehicle technologies that reduce collisions and improve driving.

Georgia has trailed other states in embracing the research aspect of autonomous vehicles. But what if MARTA seized the lead with an autonomous vehicle corridor – a demonstration project – in the Clifton corridor?

Aside from Google, at least 25 companies, from Apple to Volvo, are working on the technologies. What if a fleet of lightweight, electric-powered, Google-type vehicles, each with a capacity for four people, could quickly and quietly travel along a dedicated corridor – perhaps grade-separated, but at least fenced off – and zip off the lane to a stop near passengers’ destinations before merging back onto the corridor?

If the needs are greater, the vehicles can be larger – like the “plane train,” the Atlanta airport’s rubber-tired transportation traveling between concourses; if the needs are less, point-to-point small cars will have lower operating costs.

Neighbors would be more receptive. Infrastructure costs and needs would be lower than for rail. The lightweight, driverless fleet could even be 3D-printed; autonomous vehicles travelling at a constant speed on a dedicated lane are unlikely to be in a collision. The contained environment and the vehicles’ adaptive cruise control will minimize liability.

The beauty of such a demonstration project is that, unlike fixed rail, the lane could be used by transit vehicles with drivers and eventually include other autonomous vehicles aside from this “SyncTrans” system.

As Randal O’Toole of the Cato Institute noted recently, federal transit data show that Atlanta transit ridership has declined every year since 2009 and was lower in 2014 than in any of the previous 30 years. Since the region’s population has grown by nearly 150 percent during those years, per capita transit ridership has dropped by more than 60 percent since 1985.

Continuing to resort to 19th-century technology is unwise when a 21st-century generation prefers flexibility and innovative, personalized options like Uber, Lyft, Zip cars and other ride-sharing enterprises. Writing about the folly of California’s high-speed rail plan in Forbes, Tim Worstall points out, “[I]f we’ve got self-driving cars, then the opportunity cost of being able to move out of a car onto a faster train pretty much disappears.”

Atlanta was not named last month when the federal Department of Transportation announced finalists for its “Smart Cities” grant: $40 million to become the first city to fully integrate innovative technologies – self-driving cars, connected vehicles and smart sensors – into the transportation network.

Still, $40 million is a drop in the ocean considering the exorbitant cost estimates for fixed rail in the Clifton Corridor. The SyncTrans concept might have been dismissed as pie-in-the-sky 15 years ago, but the technology is here today. It won’t take 15 years for it to be reality.

Benita M. Dodd is vice president of the Georgia Public Policy Foundation, an independent think tank that proposes market-oriented approaches to public policy to improve the lives of Georgians. Nothing written here is to be construed as necessarily reflecting the view of the Georgia Public Policy Foundation or as an attempt to aid or hinder the passage of any bill before the U.S. Congress or the Georgia Legislature.

© Georgia Public Policy Foundation (April 15, 2016). Permission to reprint in whole or in part is hereby granted, provided the author and her affiliations are cited.

By Benita Dodd

Rail transit as a mass transportation mode is one of the least effective, most expensive options for metro Atlanta, whose reputation as the poster child for sprawl has been earned. The region’s low density makes the mode supremely inefficient and the innovations in transportation make it archaic. Yet rail proponents barely bat an eye at these realities as they continue the campaign to expand MARTA rail.

The Georgia Public Policy Foundation, as it observes the rail discussion, has long held that one of the least objectionable rail corridors would be the Clifton corridor. The corridor is one of the metro area’s most congested commutes, with major employers such as Emory University and Hospital, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Children’s Healthcare at Egleston and the VA Hospital.

That Atlanta has held off rail expansion since 2000 is to its advantage. Unlike Houston, Dallas and other metro areas, instead of relegating commuters to rail, the city can incorporate innovations that are transforming transportation’s future: autonomous vehicles and ride-sharing.

SyncTrans vehicles, as envisioned in the 2001 study published by the Georgia Public Policy Foundation. Today, autonomous vehicles would serve.

Fifteen years ago, the Foundation published a paper proposing SyncTrans, a system with “small family-sized cars that travel non-stop on an elevated guideway between stations. The quiet, electric-powered system and its cars require no drivers and can operate 24 hours a day, seven days a week. The elevated guideways are cost effective and can be erected quickly. Since the system is fully automated, labor costs are minimal.”

Fifteen years ago, the concept was Disney-Worldish and Jetsonesque. But today, Google cars travel through urban streets and auto manufacturers are uniting behind autonomous vehicle technologies that reduce collisions and improve driving.

Georgia has trailed other states in embracing the research aspect of autonomous vehicles. But what if MARTA seized the lead with an autonomous vehicle corridor – a demonstration project – in the Clifton corridor?

Aside from Google, at least 25 companies, from Apple to Volvo, are working on the technologies. What if a fleet of lightweight, electric-powered, Google-type vehicles, each with a capacity for four people, could quickly and quietly travel along a dedicated corridor – perhaps grade-separated, but at least fenced off – and zip off the lane to a stop near passengers’ destinations before merging back onto the corridor?

If the needs are greater, the vehicles can be larger – like the “plane train,” the Atlanta airport’s rubber-tired transportation traveling between concourses; if the needs are less, point-to-point small cars will have lower operating costs.

Neighbors would be more receptive. Infrastructure costs and needs would be lower than for rail. The lightweight, driverless fleet could even be 3D-printed; autonomous vehicles travelling at a constant speed on a dedicated lane are unlikely to be in a collision. The contained environment and the vehicles’ adaptive cruise control will minimize liability.

The beauty of such a demonstration project is that, unlike fixed rail, the lane could be used by transit vehicles with drivers and eventually include other autonomous vehicles aside from this “SyncTrans” system.

As Randal O’Toole of the Cato Institute noted recently, federal transit data show that Atlanta transit ridership has declined every year since 2009 and was lower in 2014 than in any of the previous 30 years. Since the region’s population has grown by nearly 150 percent during those years, per capita transit ridership has dropped by more than 60 percent since 1985.

Continuing to resort to 19th-century technology is unwise when a 21st-century generation prefers flexibility and innovative, personalized options like Uber, Lyft, Zip cars and other ride-sharing enterprises. Writing about the folly of California’s high-speed rail plan in Forbes, Tim Worstall points out, “[I]f we’ve got self-driving cars, then the opportunity cost of being able to move out of a car onto a faster train pretty much disappears.”

Atlanta was not named last month when the federal Department of Transportation announced finalists for its “Smart Cities” grant: $40 million to become the first city to fully integrate innovative technologies – self-driving cars, connected vehicles and smart sensors – into the transportation network.

Still, $40 million is a drop in the ocean considering the exorbitant cost estimates for fixed rail in the Clifton Corridor. The SyncTrans concept might have been dismissed as pie-in-the-sky 15 years ago, but the technology is here today. It won’t take 15 years for it to be reality.

Benita M. Dodd is vice president of the Georgia Public Policy Foundation, an independent think tank that proposes market-oriented approaches to public policy to improve the lives of Georgians. Nothing written here is to be construed as necessarily reflecting the view of the Georgia Public Policy Foundation or as an attempt to aid or hinder the passage of any bill before the U.S. Congress or the Georgia Legislature.

© Georgia Public Policy Foundation (April 15, 2016). Permission to reprint in whole or in part is hereby granted, provided the author and her affiliations are cited.