The renowned and influential come in all sizes. Some have an aura larger than life. Some reveal themselves smaller in character or decency than becomes a person of great public stature.

Then there are the ones around whom everything just seems to fit right. That, for me, was Jim Wooten.

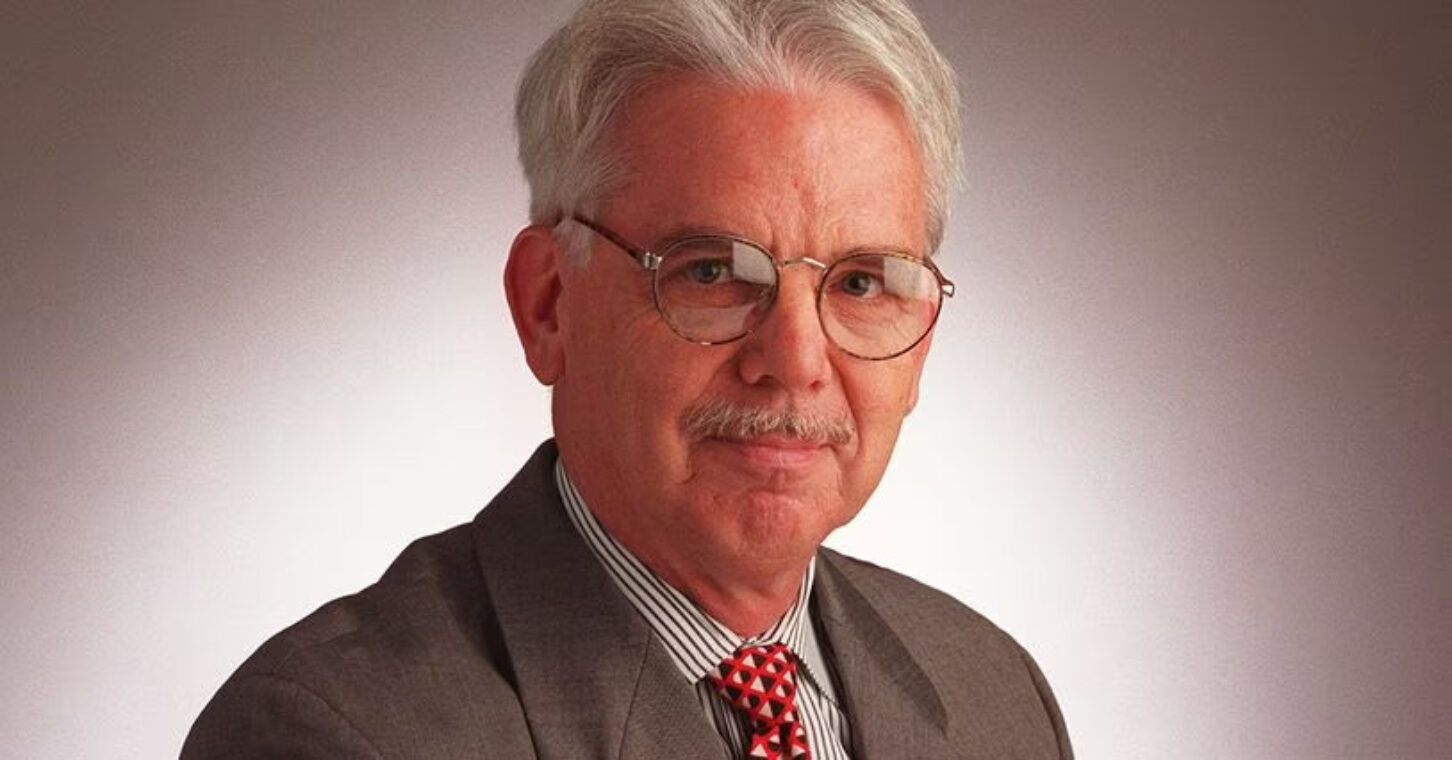

Jim died October 29, at the age of 78, after a long decline owing to Lewy body dementia. How wrong, that such a ruthless neurological disease would afflict a man with such a first-rate mind.

And what a mind his was. Jim’s columns and editorials for The Atlanta Journal, and later the combined Atlanta Journal-Constitution, were path lights for a conservative movement in Georgia that had to be formed out of the red clay before stumbling its way to prominence. Friends describe him as “a beacon of light” and an encouragement as they set about building new institutions (like the one I work for).

Although I grew up reading his work, I only got to know him at the end of his career. The AJC hired me in 2009 to succeed him. Succeed, not replace; there was no replacing Jim Wooten.

At the time, he was more than twice my 30 years. Looking back, he was patient – Lord, he had to be, when I think back on all that I thought I knew – but also intentional about giving me a crash course in all I was about to encounter. He pointed out pitfalls and schemers, introduced me to confidants and big shots.

He came as advertised: courtly and gracious. He was a snappy dresser, and equally at home in the greasy spoons along downtown’s Broad Street and the dark-paneled rooms of the Commerce Club (the old one).

Jim was not only smart but wise, even sagacious. He understood the world coolly: as it was, rather than how one might wish it to be. He’d grown up poor, raised by his mother in Macon’s public housing after his parents divorced. But he didn’t consider himself a victim or disavow his roots. He bought land in his native Telfair County (including the old mansion of Gov. Eugene Talmadge, which Jim and his wife, Ann, restored) and spent much of his retirement there.

All of which is to say, he understood life is often good but rarely neat and easy. The essence of conservatism, real conservatism, is found in such an understanding. I believe that’s where Jim’s sense of it all was rooted. He knew other Georgians, maybe most at that time, also knew hardships. His writing spoke to, and for, them.

But don’t get the wrong idea. To borrow from Mike Huckabee: Jim was a conservative, but he wasn’t mad at everybody over it. He was quick to tell a joke or laugh at one, those twinkling eyes behind his glasses doing much of the work.

And oh, was he a happy warrior. He leavened heavy topics with two indispensable ingredients: the humility born of his experiences, and a gentle, winsome humor.

Jim’s writing was beguilingly subtle. His columns ran as often as thrice weekly, mostly in the years before print’s own decline, yielding a familiarity and trust between columnist and reader that is sadly diminished nowadays. He treated his missives like one side of a long-running conversation, and he treated his readers with respect – even the disagreeable ones.

“Sometimes,” he advised me, “the best answer you can give a reader is, ‘You may be right.’”

He was a watchdog against corruption, a warning post against spendthrift politicians, an evangelist for common sense. Slowly but surely, his voice reshaped the contours of Georgia politics.

But here lay the subtlety. As deeply, consequentially conservative as he was, Jim wasn’t necessarily branded as such; he once told me that it was only after a column praising first-term George W. Bush that many readers cottoned on to his political persuasion. In his time one could be a writer and a conservative, without being pigeonholed as A Conservative Writer.

In that and so many other ways, Jim was emblematic of his era – an era that, like him, has passed on. Everything doesn’t seem to fit quite right without them.