By Kelly McCutchen

There is no question Georgia’s rural hospitals are struggling. The great majority of these hospitals are losing money every year and several have been forced to close. Their struggles were one of the primary reasons cited for Medicaid expansion. But before throwing money at the problem, it’s important to understand one of the fundamental causes: a massive unfunded mandate from the federal government.

In 1986, Congress passed, and President Ronald Reagan signed, the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA) requiring hospital emergency departments to treat and stabilize all patients regardless of their ability to pay. Unfortunately, Congress didn’t appropriate funding to cover the cost.

Imagine a law that required McDonald’s to give away food or Holiday Inn to provide a free room to anyone who shows up at their door who says they can’t afford to pay. While helping the poor is laudable, you can imagine the problems this would cause.

The Georgia Hospital Association estimates Georgia hospitals provide $1.02 billion of health care services to indigent Georgia citizens in 2014. Who is paying for those services? We all are, either through higher taxes or higher medical costs.

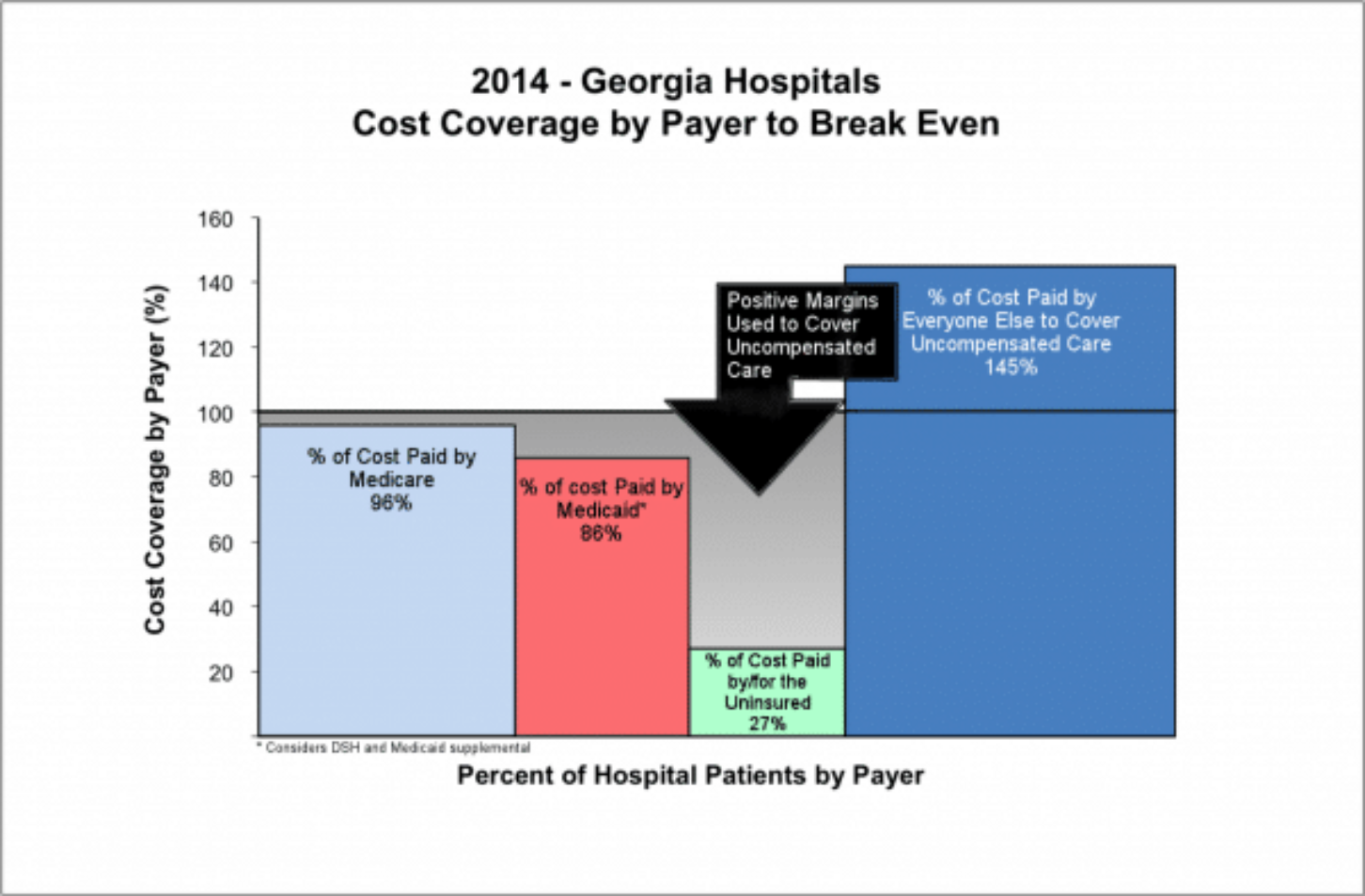

The accompanying chart from the Georgia Hospital Association shows how Georgia hospitals lose money on the majority of their patients due to below-cost government price controls on Medicare and Medicaid and even greater losses on uninsured patients. The result: Patients with private insurance pay over 40 percent more than necessary to make up for the losses.

Clearly, if the federal government funded its mandate this would provide immediate relief to Georgia taxpayers and citizens: If hospital uncompensated care is fully paid for there is no need to overcharge private payers. With hospital costs making up about a quarter of all health care expenses, a reduction of 40 percent in hospital costs could reduce overall health care costs by 10 percent. That equates to more than $300 million a year in savings just for state government employees and teachers, and larger amounts for Georgia employers and families.

How do we accomplish this commonsense feat in today’s difficult political environment?

Under current law, the federal government has committed to increase funding by $3 billion to $4 billion if Georgia expands its Medicaid program. The problem with this approach is clear by looking again at the chart: Medicaid reimburses hospitals for only 86 percent of their costs. Can’t we come up with a better plan than spending several billion dollars and still leaving our hospitals losing money? Granted, for hospitals, it’s better than the status quo, but not a long-term solution.

What do Republican plans look like? Each of the three major Republican plans that have been introduced – Burr-Hatch-Upton, Price and Sessions-Cassidy – plus Speaker Ryan’s Better Way plan, include provisions for individuals to receive a refundable tax credit (think of it as a voucher) for health care. The amounts vary by age and geography, but the average amount is around $2,500. Another provision allows for unused tax credits (from individuals who are eligible for the tax credits but don’t sign up for insurance) to be dedicated to support safety net providers. We propose combining these concepts to eliminate the unfunded federal mandate and provide care for low-income, uninsured Georgians.

How much funding would this amount to for Georgia? A recent study by Deloitte estimated 565,000 uninsured Georgians with incomes below the federal poverty line. Under any likely Republican plan, there would be approximately $1.4 billion (565,000 x $2,500) in federal dollars available to pay for the health care expenses of these indigent patients. Worst case, that’s more than enough to fully reimburse hospitals for their uncompensated indigent care. Best case, there is enough money for more comprehensive coverage that each community could customize to meet their own specific situation. Savings would be reinvested in the community to further improve services.

Consider these two approaches, both of which could be fully funded under this proposal for Georgia:

Altoona, Pennsylvania: According to the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, this direct primary care model “began as a $99 per month program that offered patients full preventive and sickness visits, full lab and diagnostics, and full hospitalization with a vast assortment of common medications provided free or at low cost. Three years later, the rates have not increased on a population that is 100 percent sick – the worst ‘adverse selection’ group an insurance company can imagine. Contrary to popular opinion from the status quo predictors, the health of the group is improving and the admission rates to the hospital and ER are lower than similar physician groups in the area and are far less than traditional group plan admission rates that, in theory, offer more Cadillac benefits.”

Grady Health System, Atlanta, Georgia: In 2015, Grady and community health providers proposed transforming how they deliver care to the uninsured by enrolling 50,000 currently uninsured Fulton and DeKalb County residents in a model that would rely on strong patient engagement and care coordination with value-based care delivery with payments based on quality results and reduced cost per patient. The proposal is patterned after successful efforts at safety net hospitals in Minneapolis and Cleveland that reduced the costs of care while improving outcomes. By transforming how healthcare is delivered and reimbursed, Grady estimated a potential cost reduction of 12-17 percent achieved through reduction in utilization of the highest cost areas, a 23-35 percent net reduction in emergency room use and an estimated 9-13 percent reduction in inpatient services. This care model would emphasize preventive and wellness services to address the social determinants that prevent utilization of the health system in the right place at the right time. Memorial Health System in Savannah estimated similar results when applying this model to their community.

Democrats and Republicans will have their differences in health care policy, but we should all be able to agree that forcing hospitals to treat patients without payment has proved to be a terribly misguided policy. That’s why we’ve encouraged the State of Georgia to negotiate a federal waiver that fully funds the cost of caring for our indigent patients.

This is essentially an insurance policy against delay in Washington, an interim demonstration project that would end once replacement legislation is finalized. Who knows how long it will take to find enough votes to replace the Affordable Care Act? This would provide immediate help to struggling Georgians and struggling health care providers. It improves access to care for the poor and lowers the cost of care for consumers while empowering flexible, local solutions. By addressing one of health care’s fundamental problems, it should also make it easier for our leaders in Washington to find common ground.

Kelly McCutchen is President of the Georgia Public Policy Foundation, an independent think tank that proposes market-oriented approaches to public policy to improve the lives of Georgians. Nothing written here is to be construed as necessarily reflecting the view of the Georgia Public Policy Foundation or as an attempt to aid or hinder the passage of any bill before the U.S. Congress or the Georgia Legislature.

© Georgia Public Policy Foundation (January 20, 2017). Permission to reprint in whole or in part is hereby granted, provided the author and his affiliations are cited.

By Kelly McCutchen

There is no question Georgia’s rural hospitals are struggling. The great majority of these hospitals are losing money every year and several have been forced to close. Their struggles were one of the primary reasons cited for Medicaid expansion. But before throwing money at the problem, it’s important to understand one of the fundamental causes: a massive unfunded mandate from the federal government.

In 1986, Congress passed, and President Ronald Reagan signed, the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA) requiring hospital emergency departments to treat and stabilize all patients regardless of their ability to pay. Unfortunately, Congress didn’t appropriate funding to cover the cost.

Imagine a law that required McDonald’s to give away food or Holiday Inn to provide a free room to anyone who shows up at their door who says they can’t afford to pay. While helping the poor is laudable, you can imagine the problems this would cause.

The Georgia Hospital Association estimates Georgia hospitals provide $1.02 billion of health care services to indigent Georgia citizens in 2014. Who is paying for those services? We all are, either through higher taxes or higher medical costs.

The accompanying chart from the Georgia Hospital Association shows how Georgia hospitals lose money on the majority of their patients due to below-cost government price controls on Medicare and Medicaid and even greater losses on uninsured patients. The result: Patients with private insurance pay over 40 percent more than necessary to make up for the losses.

Clearly, if the federal government funded its mandate this would provide immediate relief to Georgia taxpayers and citizens: If hospital uncompensated care is fully paid for there is no need to overcharge private payers. With hospital costs making up about a quarter of all health care expenses, a reduction of 40 percent in hospital costs could reduce overall health care costs by 10 percent. That equates to more than $300 million a year in savings just for state government employees and teachers, and larger amounts for Georgia employers and families.

How do we accomplish this commonsense feat in today’s difficult political environment?

Under current law, the federal government has committed to increase funding by $3 billion to $4 billion if Georgia expands its Medicaid program. The problem with this approach is clear by looking again at the chart: Medicaid reimburses hospitals for only 86 percent of their costs. Can’t we come up with a better plan than spending several billion dollars and still leaving our hospitals losing money? Granted, for hospitals, it’s better than the status quo, but not a long-term solution.

What do Republican plans look like? Each of the three major Republican plans that have been introduced – Burr-Hatch-Upton, Price and Sessions-Cassidy – plus Speaker Ryan’s Better Way plan, include provisions for individuals to receive a refundable tax credit (think of it as a voucher) for health care. The amounts vary by age and geography, but the average amount is around $2,500. Another provision allows for unused tax credits (from individuals who are eligible for the tax credits but don’t sign up for insurance) to be dedicated to support safety net providers. We propose combining these concepts to eliminate the unfunded federal mandate and provide care for low-income, uninsured Georgians.

How much funding would this amount to for Georgia? A recent study by Deloitte estimated 565,000 uninsured Georgians with incomes below the federal poverty line. Under any likely Republican plan, there would be approximately $1.4 billion (565,000 x $2,500) in federal dollars available to pay for the health care expenses of these indigent patients. Worst case, that’s more than enough to fully reimburse hospitals for their uncompensated indigent care. Best case, there is enough money for more comprehensive coverage that each community could customize to meet their own specific situation. Savings would be reinvested in the community to further improve services.

Consider these two approaches, both of which could be fully funded under this proposal for Georgia:

Altoona, Pennsylvania: According to the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, this direct primary care model “began as a $99 per month program that offered patients full preventive and sickness visits, full lab and diagnostics, and full hospitalization with a vast assortment of common medications provided free or at low cost. Three years later, the rates have not increased on a population that is 100 percent sick – the worst ‘adverse selection’ group an insurance company can imagine. Contrary to popular opinion from the status quo predictors, the health of the group is improving and the admission rates to the hospital and ER are lower than similar physician groups in the area and are far less than traditional group plan admission rates that, in theory, offer more Cadillac benefits.”

Grady Health System, Atlanta, Georgia: In 2015, Grady and community health providers proposed transforming how they deliver care to the uninsured by enrolling 50,000 currently uninsured Fulton and DeKalb County residents in a model that would rely on strong patient engagement and care coordination with value-based care delivery with payments based on quality results and reduced cost per patient. The proposal is patterned after successful efforts at safety net hospitals in Minneapolis and Cleveland that reduced the costs of care while improving outcomes. By transforming how healthcare is delivered and reimbursed, Grady estimated a potential cost reduction of 12-17 percent achieved through reduction in utilization of the highest cost areas, a 23-35 percent net reduction in emergency room use and an estimated 9-13 percent reduction in inpatient services. This care model would emphasize preventive and wellness services to address the social determinants that prevent utilization of the health system in the right place at the right time. Memorial Health System in Savannah estimated similar results when applying this model to their community.

Democrats and Republicans will have their differences in health care policy, but we should all be able to agree that forcing hospitals to treat patients without payment has proved to be a terribly misguided policy. That’s why we’ve encouraged the State of Georgia to negotiate a federal waiver that fully funds the cost of caring for our indigent patients.

This is essentially an insurance policy against delay in Washington, an interim demonstration project that would end once replacement legislation is finalized. Who knows how long it will take to find enough votes to replace the Affordable Care Act? This would provide immediate help to struggling Georgians and struggling health care providers. It improves access to care for the poor and lowers the cost of care for consumers while empowering flexible, local solutions. By addressing one of health care’s fundamental problems, it should also make it easier for our leaders in Washington to find common ground.

Kelly McCutchen is President of the Georgia Public Policy Foundation, an independent think tank that proposes market-oriented approaches to public policy to improve the lives of Georgians. Nothing written here is to be construed as necessarily reflecting the view of the Georgia Public Policy Foundation or as an attempt to aid or hinder the passage of any bill before the U.S. Congress or the Georgia Legislature.

© Georgia Public Policy Foundation (January 20, 2017). Permission to reprint in whole or in part is hereby granted, provided the author and his affiliations are cited.