Principles:

- Public safety is a core responsibility of government. A well-functioning criminal justice system enforces order and respect for every person’s right to property and life, and ensures that liberty does not lead to license.

- As with any government program, the criminal justice system must be transparent and include performance measures that hold it accountable for its results in protecting the public, lowering crime rates, reducing re-offending, collecting victim restitution and conserving taxpayers’ money.

- An ideal criminal justice system works to reform amenable offenders who will return to society through harnessing the power of families, charities, faith-based groups, and communities.

- Criminal prosecution should be reserved for conduct that is either blameworthy or threatens public safety, not wielded to grow government and undermine economic freedom.

- The corrections system should emphasize public safety, personal responsibility, work, restitution, community service, and treatment – both in probation and parole, which supervise most offenders, and in prisons.

- Policies for both offenders and the corrections system must align incentives with goals of public safety, victim restitution and satisfaction, and cost-effectiveness, moving from a system that expands when it fails to one that rewards results.[1]

Recommendations:

- Restore judicial discretion in certain cases so that judges can tailor sentences to fit the unique circumstances of each crime.

- Eliminate the use of probation for some offenses.

- Reclassify some traffic offenses to civil infractions.

- Seek meaningful reform of civil asset forfeiture law.

Facts:

The findings from the 2011 and 2012 Georgia Council on Criminal Justice Reform reports highlight Georgia’s challenges before reform and the 2016 report highlights the progress made.

2011 Report of the Georgia Council on Criminal Justice Reform:

- One in every 13 adults under criminal justice supervision, the highest rate in the country.

- One in every 70 adults under incarceration, the fourth highest percentage in the country.

- 234,000 adults incarcerated, on parole or on probation in 2010.

- Fewer than 30,000 incarcerated adults in 1990; 44,000 in 2000;56,000 in 2010.

- Projections of 60,000 incarcerated adults within five years if no reforms were undertaken.

- $500 million in 1990 annual state prison spending; $1.1 billion in 2010 comparable spending.

- State prisons at 107 percent capacity, with thousands more state prisoners in county jails.

- Recidivism rates (within three years of release) above 30 percent.

- $264 million would be required to build new prisons within five years without reforms

2012 Report of the Georgia Council on Criminal Justice Reform:

- National and state juvenile crime has steadily declined but costs and recidivism are unacceptable.

- Georgia budgeted $300 million for the state Department of Juvenile Justice in Fiscal 2013.

- $90,000 is the cost to incarcerate one juvenile for one year vs. $18,000 for an adult inmate.

- 65 percent of youths released from a juvenile state prison committed a new offense within three years.

- 24 percent of incarcerated youths in 2011 were sentenced for status offenses or misdemeanors. (Status offenders are youths who commit actions that would not be crimes if they were adults, for instance, school truancy.)

- Many areas of the state have limited or no community-based program services for youths.

- Risk and needs assessment tools were not being used effectively to inform decision-making.

- A complex patchwork of juvenile courts in 159 counties made uniform data collection impossible.

2016 Report of the Georgia Council on Criminal Justice Reform:

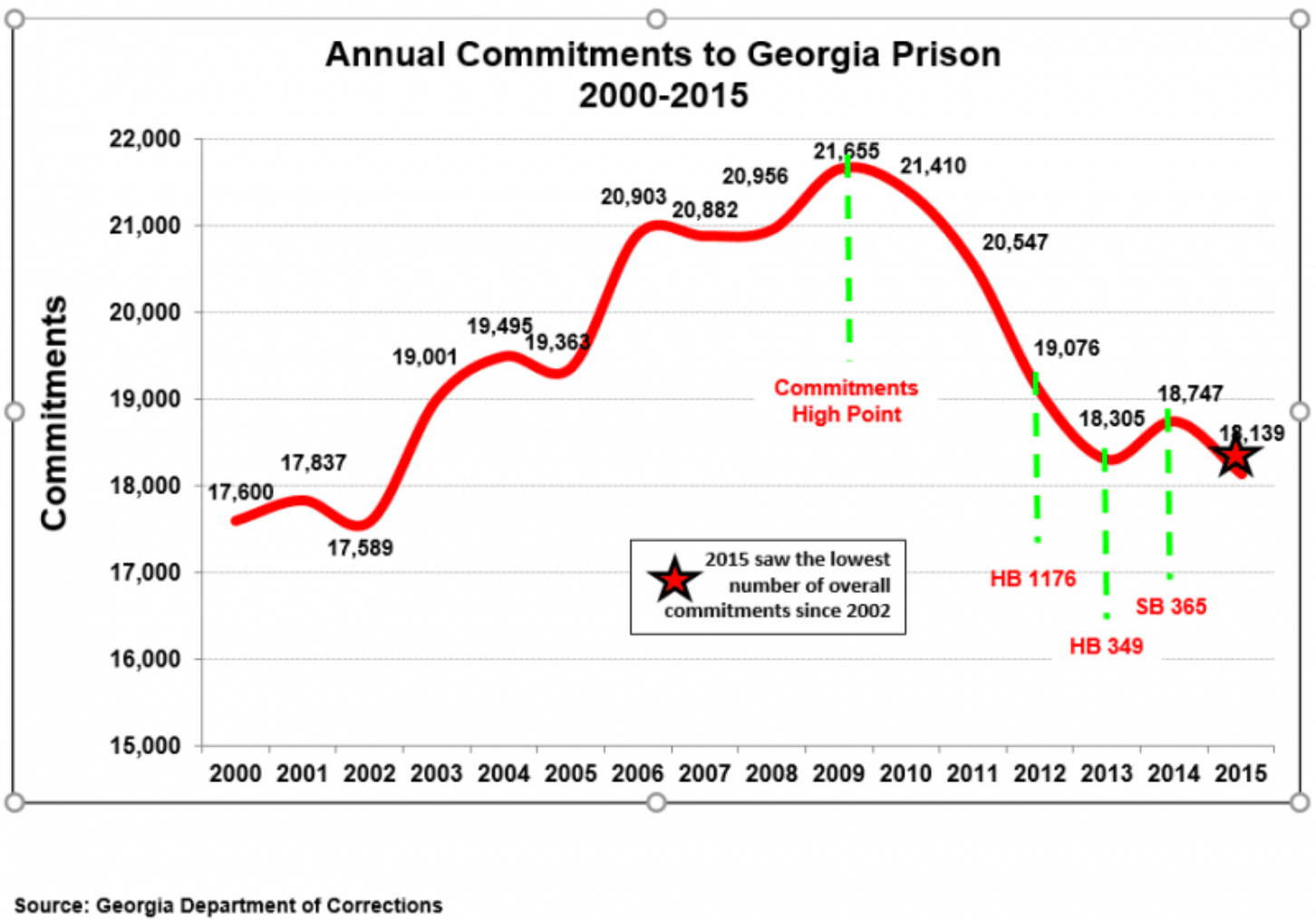

- Prison population decreased 6 percent, from 54,895 in July 2012 to 51,822 at the end of 2015.

- Prison admissions declined 16.3 percent.

- The number of African-American admissions in 2015 was the lowest since 1988.

- Fewer Georgians are in prison for non-violent offenses (In 2011 nearly 50 percent of the state’s prison population was considered non-violent vs. only 33 percent in 2015).

- There are more than 130 accountability courts that have served 3,500 Georgians statewide.

- The recidivism rate has declined from 30 percent in 2009 to 26.4 percent in 2015.

- Significant reductions in jail backlogs saving nearly $20 million for reinvestment in other initiatives.

Overview

Georgia has been recognized nationally for the sweeping adult and juvenile justice reforms it has passed since the special council’s recommendations. The reforms are projected to save about $350 million over five years, of which $20 million had already been realized by the end of 2013.

After decades of growth, in 2010 Georgia’s prison population began to decline and has declined every year since. The chart above[2] shows Georgia’s state prison population declining as the state’s overall crime rate continues its long-term decline. Violent and property crime rates are both at their lowest level in more than 40 years.

The major reforms passed in 2012 and 2013 are just beginning to have an effect, but most of the reduction in the state prison population to date can be traced to previous reforms started in 2009, including:

- Opening additional Day Reporting Centers and Residential Substance Abuse Treatment Centers to give the judiciary a viable number of community alternatives to expensive prison beds.

- Focusing resources on geographic “hot spots:” ZIP codes where large numbers of prison commitments originate.

- Creating specially trained probation officers (Probation Officer Sentencing Specialists) to work closely with the judiciary to inform them of available alternatives to prison beds.

- Creating Community Impact Programs: collaborative programs located in several hot spots where the State Board of Pardons and Paroles, local law enforcement and community- based service providers provide a one-stop-shop of services for offenders to help reduce their return to prison.

- Expanding Specialty Courts. Data show that offenders who are in accountability courts are less likely to violate their probation and ultimately return to prison.

- Implementation of swift, certain and proportionate sanctioning for probation violators. The Probation Options Management program allowed departmental hearing officers to handle low-level technical and misdemeanor violations of probation. Hearing officers were allowed to send the offenders to community or secure alternatives but not to prison. This reduced the number of cases before the judiciary and ultimately the number of cases that could have ended up in prison.

The Reform Process:

- 2009: Pew Charitable Trusts Public Safety Performance Project reports one in 31 Americans is under criminal justice system supervision. In Georgia the ratio is one in 13, highest in the nation.

Highlights Prior to Reforms

One in every 13 Georgia adults are under criminal justice supervision, the highest rate in the country.

One in every 70 Georgia adults are incarcerated, the fourth highest percentage in the country.

Prison spending has increased from $500 million in 1990 to $1.1 billion in 2010.

Recidivism rates (within three years of release) are above 30 percent for adults and 65 percent for youths released from juvenile state prisons.

It costs $90,000 per year to incarcerate one juvenile and $18,000 for an adult inmate.

Recently passed reforms are projected to save Georgia taxpayers about $350 million over five years, of which $20 million had already been realized by the end of 2013.

- 2011: Georgia Legislature created the Special Council on Criminal Justice Reform, which was tasked to study and make recommendations to modernize the adult criminal justice system.

- November 2011: The Special Council reports its findings.

- 2012: the Legislature unanimously passes HB 1176, a modernization of adult criminal justice. The key features are hard time for hard crimes, alternative programs for lesser crimes, better funding for local programs and an estimated $264 million saved by not building new prisons.

- 2012: Governor Nathan Deal extends the Special Council by executive order and charges it with making recommendations to modernize the juvenile justice system.

- 2013: The Legislature passes HB 242. Based on many of the Special Council’s juvenile justice reform recommendation, it includes a sweeping rewrite of the state’s juvenile code.

- 2013: The Legislature passes HB 349, adding to adult criminal justice system changes of 2012. It creates a Georgia Council on Criminal Justice Reform, the oversight entity for all adult and juvenile justice system reforms and implementation through at least June 30, 2018. The new Council focuses on what happens to former offenders after incarceration.

- 2015: The Legislature is expected to consider Council recommendations on adult re-entry into the community following incarceration and on the rate of recidivism. Governor Nathan Deal also asked the Council for recommendations on civil asset forfeiture law reform.

Phase One: Georgia’s Adult Justice Challenge:

The Special Council concluded incarceration should concentrate on violent offenders who pose a public safety threat; non-serious offenders should be diverted to community-based treatment. It also found there was insufficient funding to significantly support alternative programs. The report recommended expansion of accountability courts with better access to drug and mental health services, and more assistance for veterans.

The 2012 Legislature largely enacted serious offender incarceration and less serious offender alternative treatment recommendations. A robust package of ideas was included that sought to bring justice system agencies more into alignment to avoid duplication, for instance, having more than one agency simultaneously handle an individual offender after incarceration.

The Legislature addressed mandatory minimum sentences in 2013, allowing discretion in a limited number of very specific cases when the judge, prosecution and defense counsel agree a lesser sentence is appropriate. A new model was created for drug trafficking prosecutions with incarceration and fines based on the weight of the illegal drug being trafficked.

Phase Two: Georgia’s Juvenile Justice Challenge:

The juvenile recommendations, not surprisingly, were similar to ideas advanced one year earlier for adults: Focus youth detention on higher-risk serious offenders and reduce recidivism by strengthening evidence-based community supervision and programs. The Council concluded the number of detained youths could be reduced from more than 1,900 to less than 1,300 within five years (the 2018 calendar year), and the state could save $85 million over the same period. New voluntary grant programs were proposed to help support the development of community resources.

The Council proposed a new two-tier Designated Felony Act to differentiate between serious felonies, such as murder or assault with a weapon, and less serious felonies such as smash-and-grab burglary. Importantly, the Council said status offenders and some misdemeanor offenders should no longer be assigned to residential commitment.

In 2013, Provost Academy Georgia was selected to offer digital learning options to juveniles under state supervision.

Phase Three: Georgia’s Re-Entry Challenge:

The 2013 work of the Georgia Council on Criminal Justice Reform focused on barriers to re-entry, which include:

- Inadequate housing, employment, job training, general education and available medical care.

- Insufficient community-based programs and insufficient funds to support those programs.

- Insufficient protections for employers to limit their liability when they hire former offenders.

- Transportation: If you cannot get to work or treatment, you cannot succeed outside the walls.

- Poverty: Transition becomes harder for released offenders who have no financial resources.

- Family abandonment: Families sometimes do not welcome back released offenders.

- No continuation of treatment for persons who had substance abuse issues prior to incarceration.

- Silent discrimination when potential employers realize an applicant is a former offender.

- Publicly available personal criminal history records are sometimes incomplete or inaccurate.

- Lack of liability protection for employers who hire former inmates.

Legislation passed in the 2016 session accomplished the following:

- Allows parole eligibility for those serving long sentences for drug possession.

- Improves misdemeanor probation by requiring a hearing before a person can be arrested because they could not afford to pay their fine.

- Strengthens the First Offender Act and provides comprehensive record sealing.

- Requires professional licensing boards to consider the seriousness of convictions and prohibits the consideration of irrelevant criminal convictions in the licensing process.

- Eliminates the ban on food stamps for people with felony drug convictions.

- Retroactively reinstates driver’s licenses suspended due to a drug conviction at no cost to the individual.

- Expands accountability court programs to include families in juvenile court and those charged with DUI.

- Restricts secure detention of youth who are 13 and younger except for most serious offenses.

- Requires progressive discipline by local school boards before a criminal complaint is filed against a child.

- Increases funding for young people in prison to receive high school education from a charter school.

Recommendations:

Restore judicial discretion in certain cases so that judges can tailor sentences to fit the unique circumstances of each crime.

Mandatory minimum sentences were designed to try to eliminate disparities in sentencing and reduce crime rates. The outcome of these laws, however, has been to merely shift discretion from the judges to prosecutors and criminologists who have studied these laws are skeptical that they produce significant reductions in crime rates. Georgia has already passed laws restoring judicial discretion in some drug cases. In keeping with the recent reforms and to ensure the system works efficiently by holding offenders accountable and keeping citizens safe, there is a further need to explore reforms that will: 1) ensure taxpayer funds are being spent efficiently and effectively; 2) restore discretion to judges at sentencing; 3) refine statutory sentencing ranges to ensure proportionate punishment; 4) revise sentencing enhancements based on criminal history, and 5) expand parole eligibility for certain offenders.

Eliminate the use of probation for some offenses.

Probation may not be the proper tool applied to certain individuals convicted of particular crimes. Currently one in 12 Georgians is under some form of correctional control, with more than 470,000 people on probation. The state’s rate of probation is the highest in the nation, four times the national average and more than double the rate of any other state. Many on probation do not pose a risk to public safety and the stress of such supervision only increases the likelihood of recidivism. There are insufficient resources to help probationers in need of support learn new job skills, or access rehabilitative programs such as family counseling, continuing education or subsidized housing.

Reclassify some traffic offenses to civil infractions.

All traffic offenses in Georgia are currently considered misdemeanor offenses, which means a person can be sent to jail for running a red light or for driving a few miles over the posted speed limit. The costs of incarcerating people for minor traffic offenses are inconsistent with the goal of being more fiscally responsible and reserving jail and prison beds for higher-risk individuals. Also, the impact on low-income Georgians is significant: The inability to pay fines and fees can result in incarceration, loss of a job and/or housing and other significant challenges.

Seek meaningful reform of civil asset forfeiture law.

Law enforcement officers in Georgia can seize a person’s property or money without ever charging the person with the commission of a crime. The Institute for Justice found that in 2011, 58 Georgia law enforcement agencies seized more than $2.7 million from individuals who were never charged with a crime. Moreover, the seizing agency is allowed to keep a significant share of the proceeds, which causes a distracting profit motive that is subject to abuse. In 2015, the Georgia General Assembly passed legislation that improves civil asset forfeiture, but there is still a long way to go.

[1] Right on Crime statement of principles, http://www.rightoncrime.com/the-conservative-case-for-reform/statement-of-principles/

[2] U.S. Department of Justice

|

|

Reduction in prison population after reforms.

|

|

|

|

Reduction in state inmates held in local jails.

|

|

|

Principles:

- Public safety is a core responsibility of government. A well-functioning criminal justice system enforces order and respect for every person’s right to property and life, and ensures that liberty does not lead to license.

- As with any government program, the criminal justice system must be transparent and include performance measures that hold it accountable for its results in protecting the public, lowering crime rates, reducing re-offending, collecting victim restitution and conserving taxpayers’ money.

- An ideal criminal justice system works to reform amenable offenders who will return to society through harnessing the power of families, charities, faith-based groups, and communities.

- Criminal prosecution should be reserved for conduct that is either blameworthy or threatens public safety, not wielded to grow government and undermine economic freedom.

- The corrections system should emphasize public safety, personal responsibility, work, restitution, community service, and treatment – both in probation and parole, which supervise most offenders, and in prisons.

- Policies for both offenders and the corrections system must align incentives with goals of public safety, victim restitution and satisfaction, and cost-effectiveness, moving from a system that expands when it fails to one that rewards results.[1]

Recommendations:

- Restore judicial discretion in certain cases so that judges can tailor sentences to fit the unique circumstances of each crime.

- Eliminate the use of probation for some offenses.

- Reclassify some traffic offenses to civil infractions.

- Seek meaningful reform of civil asset forfeiture law.

Facts:

The findings from the 2011 and 2012 Georgia Council on Criminal Justice Reform reports highlight Georgia’s challenges before reform and the 2016 report highlights the progress made.

2011 Report of the Georgia Council on Criminal Justice Reform:

- One in every 13 adults under criminal justice supervision, the highest rate in the country.

- One in every 70 adults under incarceration, the fourth highest percentage in the country.

- 234,000 adults incarcerated, on parole or on probation in 2010.

- Fewer than 30,000 incarcerated adults in 1990; 44,000 in 2000;56,000 in 2010.

- Projections of 60,000 incarcerated adults within five years if no reforms were undertaken.

- $500 million in 1990 annual state prison spending; $1.1 billion in 2010 comparable spending.

- State prisons at 107 percent capacity, with thousands more state prisoners in county jails.

- Recidivism rates (within three years of release) above 30 percent.

- $264 million would be required to build new prisons within five years without reforms

2012 Report of the Georgia Council on Criminal Justice Reform:

- National and state juvenile crime has steadily declined but costs and recidivism are unacceptable.

- Georgia budgeted $300 million for the state Department of Juvenile Justice in Fiscal 2013.

- $90,000 is the cost to incarcerate one juvenile for one year vs. $18,000 for an adult inmate.

- 65 percent of youths released from a juvenile state prison committed a new offense within three years.

- 24 percent of incarcerated youths in 2011 were sentenced for status offenses or misdemeanors. (Status offenders are youths who commit actions that would not be crimes if they were adults, for instance, school truancy.)

- Many areas of the state have limited or no community-based program services for youths.

- Risk and needs assessment tools were not being used effectively to inform decision-making.

- A complex patchwork of juvenile courts in 159 counties made uniform data collection impossible.

2016 Report of the Georgia Council on Criminal Justice Reform:

- Prison population decreased 6 percent, from 54,895 in July 2012 to 51,822 at the end of 2015.

- Prison admissions declined 16.3 percent.

- The number of African-American admissions in 2015 was the lowest since 1988.

- Fewer Georgians are in prison for non-violent offenses (In 2011 nearly 50 percent of the state’s prison population was considered non-violent vs. only 33 percent in 2015).

- There are more than 130 accountability courts that have served 3,500 Georgians statewide.

- The recidivism rate has declined from 30 percent in 2009 to 26.4 percent in 2015.

- Significant reductions in jail backlogs saving nearly $20 million for reinvestment in other initiatives.

Overview

Georgia has been recognized nationally for the sweeping adult and juvenile justice reforms it has passed since the special council’s recommendations. The reforms are projected to save about $350 million over five years, of which $20 million had already been realized by the end of 2013.

After decades of growth, in 2010 Georgia’s prison population began to decline and has declined every year since. The chart above[2] shows Georgia’s state prison population declining as the state’s overall crime rate continues its long-term decline. Violent and property crime rates are both at their lowest level in more than 40 years.

The major reforms passed in 2012 and 2013 are just beginning to have an effect, but most of the reduction in the state prison population to date can be traced to previous reforms started in 2009, including:

- Opening additional Day Reporting Centers and Residential Substance Abuse Treatment Centers to give the judiciary a viable number of community alternatives to expensive prison beds.

- Focusing resources on geographic “hot spots:” ZIP codes where large numbers of prison commitments originate.

- Creating specially trained probation officers (Probation Officer Sentencing Specialists) to work closely with the judiciary to inform them of available alternatives to prison beds.

- Creating Community Impact Programs: collaborative programs located in several hot spots where the State Board of Pardons and Paroles, local law enforcement and community- based service providers provide a one-stop-shop of services for offenders to help reduce their return to prison.

- Expanding Specialty Courts. Data show that offenders who are in accountability courts are less likely to violate their probation and ultimately return to prison.

- Implementation of swift, certain and proportionate sanctioning for probation violators. The Probation Options Management program allowed departmental hearing officers to handle low-level technical and misdemeanor violations of probation. Hearing officers were allowed to send the offenders to community or secure alternatives but not to prison. This reduced the number of cases before the judiciary and ultimately the number of cases that could have ended up in prison.

The Reform Process:

- 2009: Pew Charitable Trusts Public Safety Performance Project reports one in 31 Americans is under criminal justice system supervision. In Georgia the ratio is one in 13, highest in the nation.

Highlights Prior to Reforms

One in every 13 Georgia adults are under criminal justice supervision, the highest rate in the country.

One in every 70 Georgia adults are incarcerated, the fourth highest percentage in the country.

Prison spending has increased from $500 million in 1990 to $1.1 billion in 2010.

Recidivism rates (within three years of release) are above 30 percent for adults and 65 percent for youths released from juvenile state prisons.

It costs $90,000 per year to incarcerate one juvenile and $18,000 for an adult inmate.

Recently passed reforms are projected to save Georgia taxpayers about $350 million over five years, of which $20 million had already been realized by the end of 2013.

- 2011: Georgia Legislature created the Special Council on Criminal Justice Reform, which was tasked to study and make recommendations to modernize the adult criminal justice system.

- November 2011: The Special Council reports its findings.

- 2012: the Legislature unanimously passes HB 1176, a modernization of adult criminal justice. The key features are hard time for hard crimes, alternative programs for lesser crimes, better funding for local programs and an estimated $264 million saved by not building new prisons.

- 2012: Governor Nathan Deal extends the Special Council by executive order and charges it with making recommendations to modernize the juvenile justice system.

- 2013: The Legislature passes HB 242. Based on many of the Special Council’s juvenile justice reform recommendation, it includes a sweeping rewrite of the state’s juvenile code.

- 2013: The Legislature passes HB 349, adding to adult criminal justice system changes of 2012. It creates a Georgia Council on Criminal Justice Reform, the oversight entity for all adult and juvenile justice system reforms and implementation through at least June 30, 2018. The new Council focuses on what happens to former offenders after incarceration.

- 2015: The Legislature is expected to consider Council recommendations on adult re-entry into the community following incarceration and on the rate of recidivism. Governor Nathan Deal also asked the Council for recommendations on civil asset forfeiture law reform.

Phase One: Georgia’s Adult Justice Challenge:

The Special Council concluded incarceration should concentrate on violent offenders who pose a public safety threat; non-serious offenders should be diverted to community-based treatment. It also found there was insufficient funding to significantly support alternative programs. The report recommended expansion of accountability courts with better access to drug and mental health services, and more assistance for veterans.

The 2012 Legislature largely enacted serious offender incarceration and less serious offender alternative treatment recommendations. A robust package of ideas was included that sought to bring justice system agencies more into alignment to avoid duplication, for instance, having more than one agency simultaneously handle an individual offender after incarceration.

The Legislature addressed mandatory minimum sentences in 2013, allowing discretion in a limited number of very specific cases when the judge, prosecution and defense counsel agree a lesser sentence is appropriate. A new model was created for drug trafficking prosecutions with incarceration and fines based on the weight of the illegal drug being trafficked.

Phase Two: Georgia’s Juvenile Justice Challenge:

The juvenile recommendations, not surprisingly, were similar to ideas advanced one year earlier for adults: Focus youth detention on higher-risk serious offenders and reduce recidivism by strengthening evidence-based community supervision and programs. The Council concluded the number of detained youths could be reduced from more than 1,900 to less than 1,300 within five years (the 2018 calendar year), and the state could save $85 million over the same period. New voluntary grant programs were proposed to help support the development of community resources.

The Council proposed a new two-tier Designated Felony Act to differentiate between serious felonies, such as murder or assault with a weapon, and less serious felonies such as smash-and-grab burglary. Importantly, the Council said status offenders and some misdemeanor offenders should no longer be assigned to residential commitment.

In 2013, Provost Academy Georgia was selected to offer digital learning options to juveniles under state supervision.

Phase Three: Georgia’s Re-Entry Challenge:

The 2013 work of the Georgia Council on Criminal Justice Reform focused on barriers to re-entry, which include:

- Inadequate housing, employment, job training, general education and available medical care.

- Insufficient community-based programs and insufficient funds to support those programs.

- Insufficient protections for employers to limit their liability when they hire former offenders.

- Transportation: If you cannot get to work or treatment, you cannot succeed outside the walls.

- Poverty: Transition becomes harder for released offenders who have no financial resources.

- Family abandonment: Families sometimes do not welcome back released offenders.

- No continuation of treatment for persons who had substance abuse issues prior to incarceration.

- Silent discrimination when potential employers realize an applicant is a former offender.

- Publicly available personal criminal history records are sometimes incomplete or inaccurate.

- Lack of liability protection for employers who hire former inmates.

Legislation passed in the 2016 session accomplished the following:

- Allows parole eligibility for those serving long sentences for drug possession.

- Improves misdemeanor probation by requiring a hearing before a person can be arrested because they could not afford to pay their fine.

- Strengthens the First Offender Act and provides comprehensive record sealing.

- Requires professional licensing boards to consider the seriousness of convictions and prohibits the consideration of irrelevant criminal convictions in the licensing process.

- Eliminates the ban on food stamps for people with felony drug convictions.

- Retroactively reinstates driver’s licenses suspended due to a drug conviction at no cost to the individual.

- Expands accountability court programs to include families in juvenile court and those charged with DUI.

- Restricts secure detention of youth who are 13 and younger except for most serious offenses.

- Requires progressive discipline by local school boards before a criminal complaint is filed against a child.

- Increases funding for young people in prison to receive high school education from a charter school.

Recommendations:

Restore judicial discretion in certain cases so that judges can tailor sentences to fit the unique circumstances of each crime.

Mandatory minimum sentences were designed to try to eliminate disparities in sentencing and reduce crime rates. The outcome of these laws, however, has been to merely shift discretion from the judges to prosecutors and criminologists who have studied these laws are skeptical that they produce significant reductions in crime rates. Georgia has already passed laws restoring judicial discretion in some drug cases. In keeping with the recent reforms and to ensure the system works efficiently by holding offenders accountable and keeping citizens safe, there is a further need to explore reforms that will: 1) ensure taxpayer funds are being spent efficiently and effectively; 2) restore discretion to judges at sentencing; 3) refine statutory sentencing ranges to ensure proportionate punishment; 4) revise sentencing enhancements based on criminal history, and 5) expand parole eligibility for certain offenders.

Eliminate the use of probation for some offenses.

Probation may not be the proper tool applied to certain individuals convicted of particular crimes. Currently one in 12 Georgians is under some form of correctional control, with more than 470,000 people on probation. The state’s rate of probation is the highest in the nation, four times the national average and more than double the rate of any other state. Many on probation do not pose a risk to public safety and the stress of such supervision only increases the likelihood of recidivism. There are insufficient resources to help probationers in need of support learn new job skills, or access rehabilitative programs such as family counseling, continuing education or subsidized housing.

Reclassify some traffic offenses to civil infractions.

All traffic offenses in Georgia are currently considered misdemeanor offenses, which means a person can be sent to jail for running a red light or for driving a few miles over the posted speed limit. The costs of incarcerating people for minor traffic offenses are inconsistent with the goal of being more fiscally responsible and reserving jail and prison beds for higher-risk individuals. Also, the impact on low-income Georgians is significant: The inability to pay fines and fees can result in incarceration, loss of a job and/or housing and other significant challenges.

Seek meaningful reform of civil asset forfeiture law.

Law enforcement officers in Georgia can seize a person’s property or money without ever charging the person with the commission of a crime. The Institute for Justice found that in 2011, 58 Georgia law enforcement agencies seized more than $2.7 million from individuals who were never charged with a crime. Moreover, the seizing agency is allowed to keep a significant share of the proceeds, which causes a distracting profit motive that is subject to abuse. In 2015, the Georgia General Assembly passed legislation that improves civil asset forfeiture, but there is still a long way to go.

[1] Right on Crime statement of principles, http://www.rightoncrime.com/the-conservative-case-for-reform/statement-of-principles/

[2] U.S. Department of Justice

|

|

Reduction in prison population after reforms.

|

|

|

|

Reduction in state inmates held in local jails.

|

|

|