Earlier this week, Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger led the first meeting of his office’s new GA WORKS Licensing Commission. The optimistic observer may see this as Georgia’s next step toward removing barriers to work.

The Commission, which includes legislators, chamber of commerce members and experts from the private sector, looks to review Georgia’s occupational licensing practices and implement a framework to accommodate the state’s changing economy. It plans to meet multiple times this year in preparation for the 2024 legislative session.

The meeting was largely introductory. Members expressed their support for or skepticism of reducing licensing regulations in decisively generalized terms. In other words, the mere existence of this commission is not evidence of Georgia’s determination to reduce licensing requirements.

This is not to say state lawmakers have ignored the issue. Far from it. Georgia is frequently referred to as “the best state for business,” and multiple commission members stressed that licensing reform is an important factor in maintaining that claim.

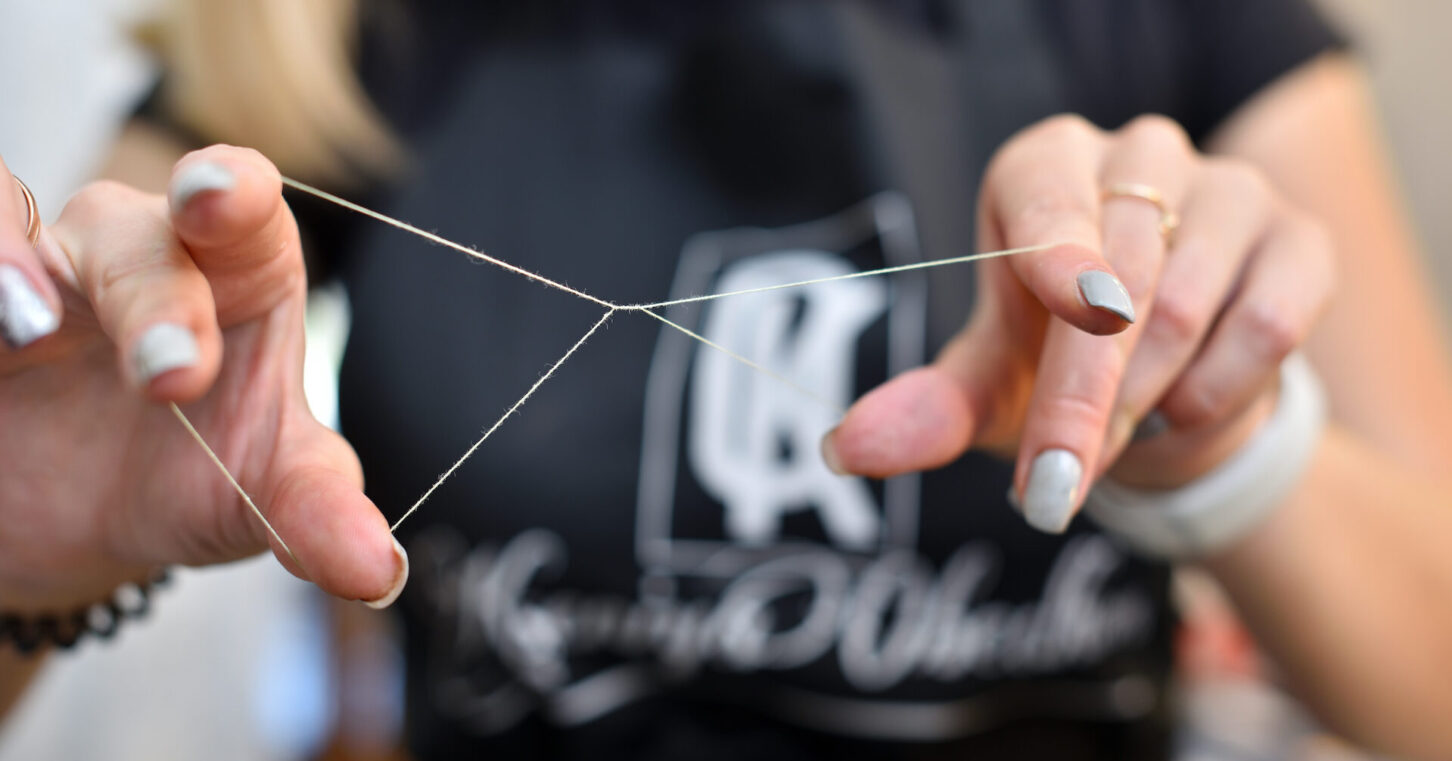

Occupational licensing was addressed in a few ways to varying degrees of impact in this year’s legislative session. House Bill 212, the Niche-Beauty Services Opportunity Act for example, would have allowed Georgians to provide services including blow dry styling, eyebrow threading and makeup artistry without a license from the State Board of Cosmetology and Barbers.

That bill’s sponsor, Rep. David Jenkins, R-Grantville, noted that it would have removed unnecessary barriers to entrepreneurship. This goal was echoed by Bert Brantley, a commission member and the President and CEO of the Savannah Chamber of Commerce. Brantley noted that harsh licensing requirements often discourage entrepreneurial entry from certain fields.

Other common issues with licensing were addressed in the session as well. House Bill 155 proposed that Georgia boards recognize out-of-state licenses held by newcomers; similar practices have been adopted in several other states. Senate Bill 157 proposed removing vague language from licensing criteria to make it easier for Georgians with criminal records to obtain an occupational license.

Of those three bills, only HB 155 was enacted. SB 157 was withdrawn after passing the Senate, and HB 212 was tabled after reaching the House floor.

Despite these less-than-inspiring results, the commission’s initial meeting touched on a few recurring themes about licensing.

For example, although SB 157 didn’t pass this year, limitations on Georgians with criminal records were highlighted as critical challenges posed by occupational licensing. The commission noted that employment is one of the biggest preventers of recidivism.

This, along with a desire to fill needs in the healthcare industry, accommodate dislocated workers, assist foreign-trained workers and generally keep up with workforce demand, demonstrates how licensing crosses into other policy issues.

Occupational licensing reform is by no means a new phenomenon, nor is it exclusive to Georgia’s legislature. The national and ubiquitous nature of the conversation has many advocates on the same page. It’s a popular sentiment that making a lemonade stand or selling used watches (as commission member Sen. Larry Walker, R-Perry, noted) should not require permission from the government.

Many similarly express support for more macro-focused licensing reforms, such as recognizing that much of the legislation and many of the statutes that dictate licensing are outdated, unnecessary and counterproductive. These practices make Georgia’s impressive growth more difficult to maintain. A growing workforce is a changing workforce, which is bound to clash with the rigidity of antiquated regulations.

The commission’s stated goals included both streamlining the licensing process and removing unnecessary or redundant licenses, although the effort is not free of skepticism.

Rep. Brian Prince, D-Augusta, cautioned the commission against overcorrecting licensing practice at the cost of public safety. However, lawmakers increasingly see the economic opportunity – if not necessity – in curbing occupational licensing.

Despite its status as “the best state for business,” Georgia does not rank highly in terms of how its licensing laws affect economic freedom. A study by the Institute for Justice published late last year showed that while Georgia requires relatively few licenses, the barriers to obtaining those licenses are relatively high. Ultimately, Georgia’s regulations ranked as the 12th-most burdensome in the country.

The effort being made in the state government to provide more freedom to Georgia workers is at least visible. The Secretary of State’s office will roll out an online license application system throughout this fall, winter and spring to help streamline the process. It has also reduced the number of licenses that take a year or longer and increased the amount of licenses that are processed in 30 days or fewer.

These measures along with the formation of the licensing commission demonstrate the state government’s interest. Whether effort will lead to impact remains to be seen. The 2023 legislative session yielded paltry results on the licensing front, but one can hope that further efforts will lead to a better landscape: one in which Georgia’s workers have more freedom and its economy’s potential can be more fully realized.