I was chatting recently with a former federal appointee who described what it’s like to work in the war of attrition known as the United States bureaucracy.

When her team took over, she explained, they found a situation that was disappointing on many levels: fiscally, operationally, morally. They first rewrote the department’s procedures to address these shortcomings. Then they tried to do as much good (as they defined it) in the time they had – knowing full well that successors of another political persuasion would then set about undoing as much of their work as possible.

It doesn’t matter which administration she served; both sides do this. It’s another sign of the decay of our institutions – and, if we don’t do something about it, of our shrinking aptitude for self-governance.

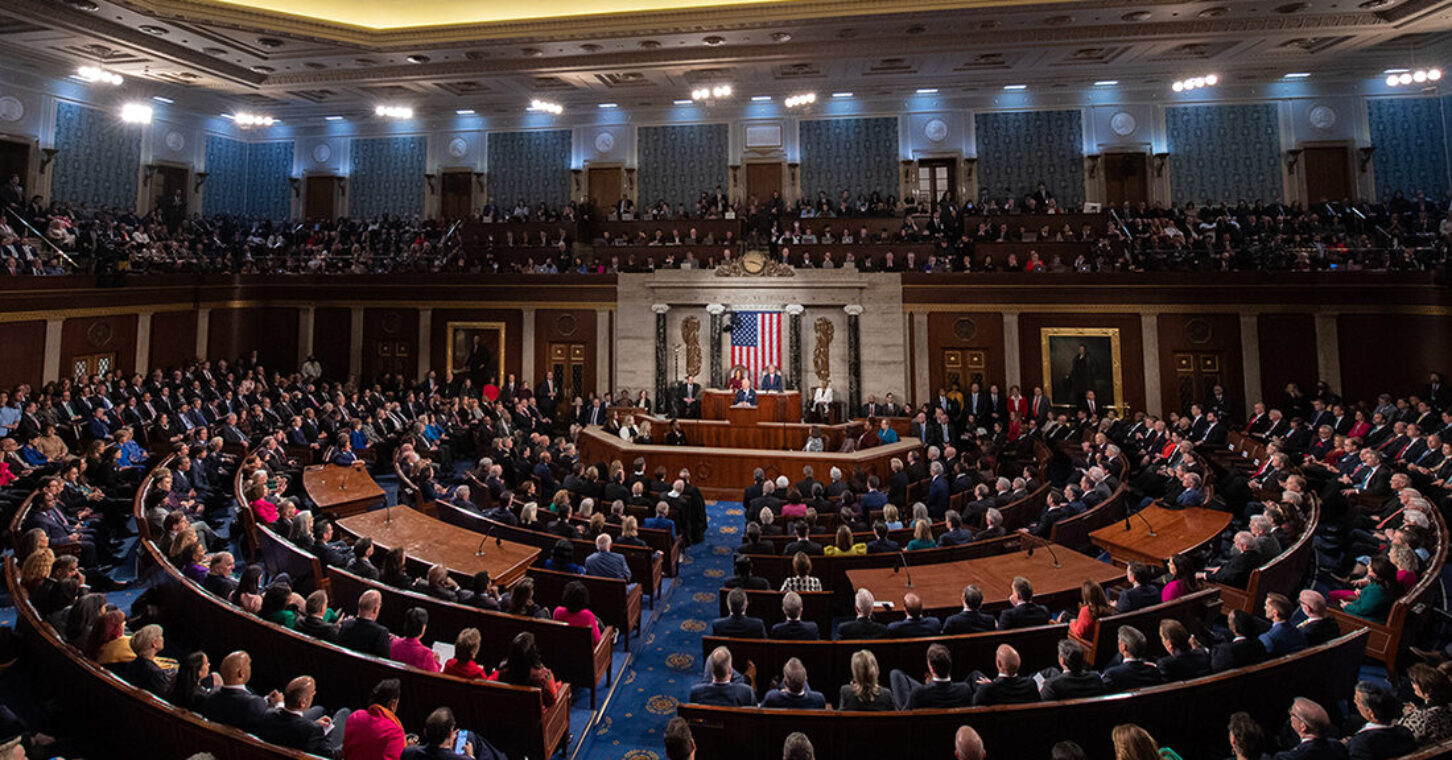

As I write this, another shutdown of the federal government seems certain. Even if it has been resolved by the time you read this, these impasses are hardly a fleeting problem.

A shutdown this year would be at least the 11th interruption of Washington’s operations for lack of funding since 1980. Joe Biden would join Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton, Barack Obama and Donald Trump in presiding over shutdowns, which have ranged from four hours to five weeks.

Shutdowns have happened with Democrats in charge of the White House and both chambers of Congress, with Republicans in control of all three, and under most permutations of divided government. They have become normal, if not routine.

Both the bureaucratic tug-of-war and these funding fights represent the same root problem: a federal government so powerful and far-reaching that partisans would rather break it occasionally than let it operate like a normal organization.

There are of course other factors. For example, the same partisanship and tribalism that lead to these polarized views of government also feed fantasies on both sides that one group is on the brink of winning a definitive victory over the other.

Considering the “pox on both houses” attitude that most voters take toward this fight, those visions of a permanent victory are beyond delusional. But these delusions motivate such behavior.

The solution in all cases is the same: Make the federal government work better by having it do less.

“Less” is not the same as “nothing,” and “better” doesn’t mean “weaker.” The Founders tried a weak, almost wholly decentralized government with the Articles of Confederation; it worked so poorly that they scrapped it within a decade.

They replaced it with the U.S. Constitution, a document that quite simply changed human history. But the longer we go, the farther we seem to get from its design.

Not surprisingly, that distance greatly weakens the central government it created.

We might describe the central government of the U.S. Constitution as all-powerful in a small number of crucial spheres, and deferential in the rest. Those crucial spheres are ones which require uniformity: things like defense and diplomacy, commerce and currency, which can’t function effectively if done differently in different states.

But most issues don’t belong in that small number. Public education, health insurance, municipal transportation networks – these are things that needn’t be agreed upon from sea to shining sea. To pretend otherwise is to force Americans with locally developed sensibilities to swallow (and pay for) notions that wouldn’t otherwise hold sway over themselves and their neighbors.

Among 335 million Americans, there is bound to be a variety of locally developed sensibilities – and an inevitability of those various sensibilities clashing. Restoring the central government to its limited set of purposes, and leaving other functions to other actors, can strengthen the federal government and defuse a number of tensions.

We celebrate that document with Constitution Day every September 17. The end of the federal budget year happens to be September 30. By getting back to the spirit of the former, we might avoid so much drama on the latter.