Puerto Rico was devastated by Hurricane Maria, but he physical, economic and social destruction caused by Maria followed economic and demographic problems that began long before the hurricane hit.

By Harold Brown

A year ago this month, the U.S. territory of Puerto Rico was devastated by Hurricane Maria. Apportioning blame and credit for the island’s recovery is almost beside the point. That has been complicated not only by the physical, economic and social destruction caused by Maria but by economic and demographic problems beginning long before the hurricane hit.

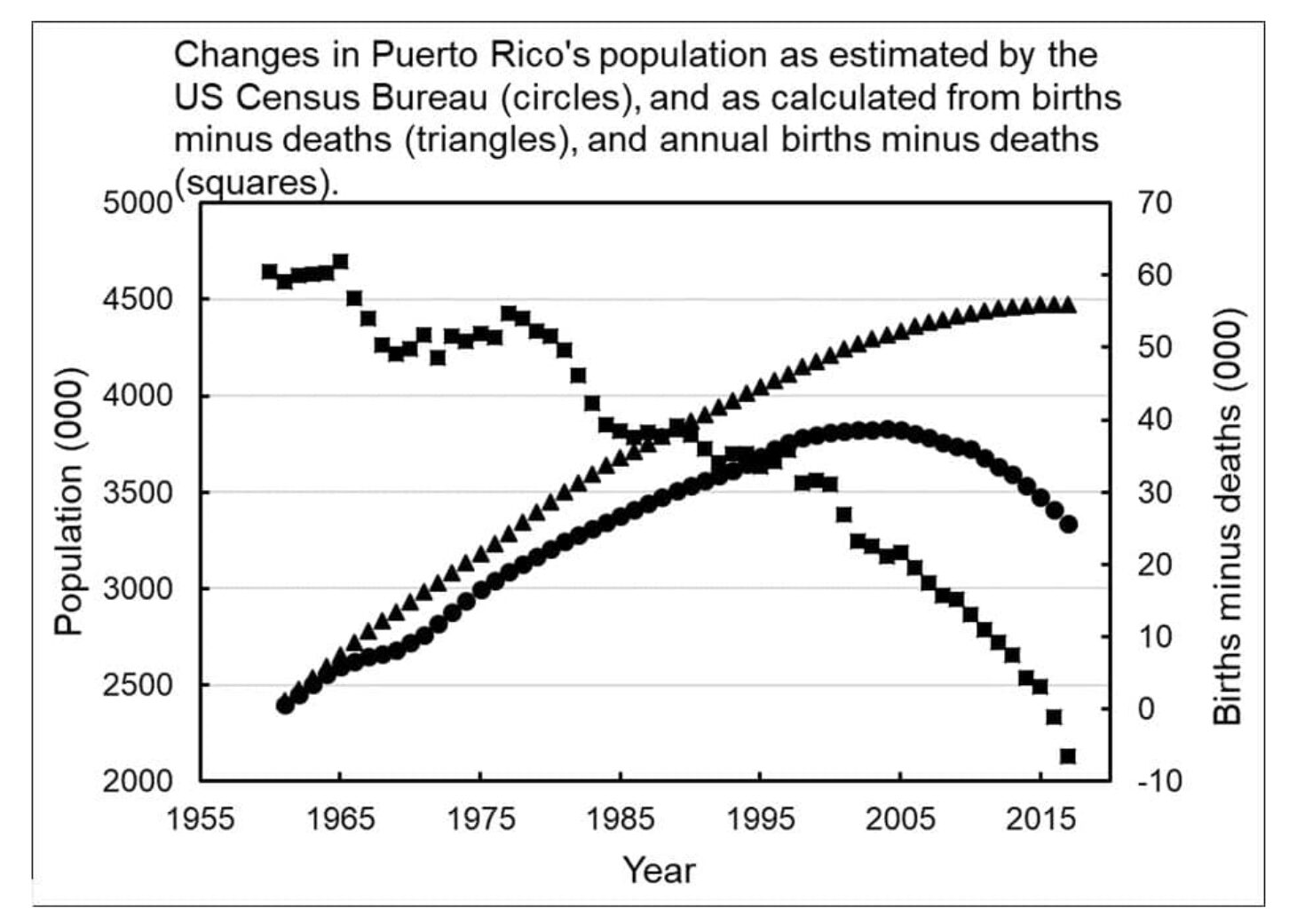

Puerto Rico is one of the few places in the world where population is in a steep decline (see chart). For 2017, the CIA World Factbook lists it second from the bottom out of 234 countries for population growth. According to the Census, the population increased until 2004, then declined, reaching the lowest population in three decades last year.

The population has grown older, too. The number of children ages 5 and younger dropped 49 percent during 2000-2017, while seniors ages 65 and older rose 54 percent. Those 85 and older increased by 74 percent.

Since 1960, the number of deaths have nearly doubled, as expected with an increasing (up to 2004) and aging population. But even as the population increased, total births decreased from about 75,000 per year in the 1960s, to 50,000 in 2004, to about 25,000 in 2017. Total fertility rate (children per woman) dropped from 4.6 to 1.2.

Fertility and mortality rates are not the only reason for the population decline. Migration to the United States is just as large a factor. Population growth calculated by adding births and subtracting deaths each year highlights the effect of emigration on the population. (See chart for the difference in population curves). Migration to the mainland since 1960 has subtracted just over 1 million from what would have been a population of about 4.5 million. (Compare 2017 points on population curves in chart.)

From 2010 to 2016, Puerto Rico had a net loss of 360,143 persons to migration, but gained only about 45,000 through births minus deaths. In the last year of this short period, there were 1,081 fewer births than deaths.

Puerto Ricans are U.S. citizens. The devastation wrought by Maria assuredly motivated even more to leave. According to USA Today, more than 140,000 Puerto Ricans left the island in less than two months after Maria hit.

Maria did not begin the migration to the mainland; it increased the recent trend. (A Library of Congress publication states that over 1 million Puerto Ricans had already moved by the mid-1960s.) The Pew Research Center reports annual net migration averaged 11,000 in the 1990s, 48,000 from 2010 to 2013 and about 65,000 in 2015 and 2016.

Sixty-seven percent more Puerto Ricans now live in the states (5.6 million in 2017) than on the island (3.3 million).

The reasons are economic and demographic; Pew reports that migrants cited job-related reasons above all others. The Puerto Rico Planning Board reported employment declined 279,000 from 2007 to 2015. The board found that while the trade balance improved nearly 30 percent from 2007 to 2015, imports were still $10 billion more than sales in 2015.At the same time, the value of public and private construction decreased by 45 percent.

The reasons are economic and demographic; Pew reports that migrants cited job-related reasons above all others. The Puerto Rico Planning Board reported employment declined 279,000 from 2007 to 2015. The board found that while the trade balance improved nearly 30 percent from 2007 to 2015, imports were still $10 billion more than sales in 2015.At the same time, the value of public and private construction decreased by 45 percent.

Puerto Rico’s GDP reached a record of nearly $109 billion in 2006, but by 2013 it had dropped to $93 billion. The falling GDP is compounded by rising debt. In the month before Maria struck the, a writer for Forbes concluded the island was in “the most severe economic crisis in its modern history,” and that its debt would climb to 107 percent of its GDP in 2018.

In May 2017, Puerto Rico declared in a New York court what The New York Times called “a form of bankruptcy,” an extraordinary procedure never before used by an American state or territory for protection from creditors.

The island’s standard of living remains far below the mainland’s and has not improved since the recession. Median household income, which has grown about 10 percent since 2009, remains about one-third of that in the states. Forty-five percent of Puerto Ricans live below the poverty line, a percentage that has not changed in over a decade. Between 2005 and 2016, households receiving public food assistance (food stamps) rose from 29 percent to 39 percent.

The reasons for the stagnation of the island’s economy and its declining population are probably more complex than they appear. What is certain, however, is that Maria’s devastation is another severe obstacle, and the flood of emigration is likely to delay and weaken Puerto Rico’s recovery.

University of Georgia Professor Emeritus Harold Brown is a Senior Fellow with the Georgia Public Policy Foundation and author of “The Greening of Georgia: The Improvement of the Environment in the Twentieth Century.” The Georgia Public Policy Foundation is an independent, nonprofit think tank that proposes market-oriented approaches to public policy to improve the lives of Georgians. Nothing written here is to be construed as necessarily reflecting the views of the Georgia Public Policy Foundation or as an attempt to aid or hinder the passage of any bill before the U.S. Congress or the Georgia Legislature.

© Georgia Public Policy Foundation (September 21, 2018). Permission to reprint in whole or in part is hereby granted, provided the author and his affiliations are cited.

By Harold Brown

A year ago this month, the U.S. territory of Puerto Rico was devastated by Hurricane Maria. Apportioning blame and credit for the island’s recovery is almost beside the point. That has been complicated not only by the physical, economic and social destruction caused by Maria but by economic and demographic problems beginning long before the hurricane hit.

Puerto Rico is one of the few places in the world where population is in a steep decline (see chart). For 2017, the CIA World Factbook lists it second from the bottom out of 234 countries for population growth. According to the Census, the population increased until 2004, then declined, reaching the lowest population in three decades last year.

The population has grown older, too. The number of children ages 5 and younger dropped 49 percent during 2000-2017, while seniors ages 65 and older rose 54 percent. Those 85 and older increased by 74 percent.

Since 1960, the number of deaths have nearly doubled, as expected with an increasing (up to 2004) and aging population. But even as the population increased, total births decreased from about 75,000 per year in the 1960s, to 50,000 in 2004, to about 25,000 in 2017. Total fertility rate (children per woman) dropped from 4.6 to 1.2.

Fertility and mortality rates are not the only reason for the population decline. Migration to the United States is just as large a factor. Population growth calculated by adding births and subtracting deaths each year highlights the effect of emigration on the population. (See chart for the difference in population curves). Migration to the mainland since 1960 has subtracted just over 1 million from what would have been a population of about 4.5 million. (Compare 2017 points on population curves in chart.)

From 2010 to 2016, Puerto Rico had a net loss of 360,143 persons to migration, but gained only about 45,000 through births minus deaths. In the last year of this short period, there were 1,081 fewer births than deaths.

Puerto Ricans are U.S. citizens. The devastation wrought by Maria assuredly motivated even more to leave. According to USA Today, more than 140,000 Puerto Ricans left the island in less than two months after Maria hit.

Maria did not begin the migration to the mainland; it increased the recent trend. (A Library of Congress publication states that over 1 million Puerto Ricans had already moved by the mid-1960s.) The Pew Research Center reports annual net migration averaged 11,000 in the 1990s, 48,000 from 2010 to 2013 and about 65,000 in 2015 and 2016.

Sixty-seven percent more Puerto Ricans now live in the states (5.6 million in 2017) than on the island (3.3 million).

The reasons are economic and demographic; Pew reports that migrants cited job-related reasons above all others. The Puerto Rico Planning Board reported employment declined 279,000 from 2007 to 2015. The board found that while the trade balance improved nearly 30 percent from 2007 to 2015, imports were still $10 billion more than sales in 2015.At the same time, the value of public and private construction decreased by 45 percent.

The reasons are economic and demographic; Pew reports that migrants cited job-related reasons above all others. The Puerto Rico Planning Board reported employment declined 279,000 from 2007 to 2015. The board found that while the trade balance improved nearly 30 percent from 2007 to 2015, imports were still $10 billion more than sales in 2015.At the same time, the value of public and private construction decreased by 45 percent.

Puerto Rico’s GDP reached a record of nearly $109 billion in 2006, but by 2013 it had dropped to $93 billion. The falling GDP is compounded by rising debt. In the month before Maria struck the, a writer for Forbes concluded the island was in “the most severe economic crisis in its modern history,” and that its debt would climb to 107 percent of its GDP in 2018.

In May 2017, Puerto Rico declared in a New York court what The New York Times called “a form of bankruptcy,” an extraordinary procedure never before used by an American state or territory for protection from creditors.

The island’s standard of living remains far below the mainland’s and has not improved since the recession. Median household income, which has grown about 10 percent since 2009, remains about one-third of that in the states. Forty-five percent of Puerto Ricans live below the poverty line, a percentage that has not changed in over a decade. Between 2005 and 2016, households receiving public food assistance (food stamps) rose from 29 percent to 39 percent.

The reasons for the stagnation of the island’s economy and its declining population are probably more complex than they appear. What is certain, however, is that Maria’s devastation is another severe obstacle, and the flood of emigration is likely to delay and weaken Puerto Rico’s recovery.

University of Georgia Professor Emeritus Harold Brown is a Senior Fellow with the Georgia Public Policy Foundation and author of “The Greening of Georgia: The Improvement of the Environment in the Twentieth Century.” The Georgia Public Policy Foundation is an independent, nonprofit think tank that proposes market-oriented approaches to public policy to improve the lives of Georgians. Nothing written here is to be construed as necessarily reflecting the views of the Georgia Public Policy Foundation or as an attempt to aid or hinder the passage of any bill before the U.S. Congress or the Georgia Legislature.

© Georgia Public Policy Foundation (September 21, 2018). Permission to reprint in whole or in part is hereby granted, provided the author and his affiliations are cited.