By Kelly McCutchen

As Congress returns next week from its Independence Day recess, health care will be front and center. Amid the noise from special interest groups drowning out substantive debate, one proposal that could enormously benefit Georgia has gone unnoticed.

The current U.S. Senate proposal, like the House version, introduces Medicaid per-capita block grants in 2020. Per-capita block grants have at one time or another been supported by both Democrats and Republicans. Putting Medicaid spending on a budget delights fiscal conservatives and deficit hawks.

As opposed to a traditional block grant, funding would adjust up and down based on the number of enrollees in the program. This protects states from surging rolls during a recession while saving federal and state money when individuals leave the program.

Unfortunately for Georgia, the initial block grant funding levels are based on historical spending, an unfair approach given the large differences in funding among the states.

Take New York. That state spends more than three times as much on disabled and elderly Medicaid recipients than does Georgia. The House legislation as passed would perpetuate this inequity.

One solution the Georgia Public Policy Foundation has proposed is what statisticians call “reversion to the mean:” Over time, high-spending states would receive less and low spending states would get more, moving all states closer to the national average. This could be accomplished by adjusting the growth rates on the block grants to avoid abrupt changes in funding.

That is exactly what the Senate has done. The latest Senate bill (page 64) authorizes the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services to increase state block grants by up to 2 percent per year in states spending less than 25 percent of the national average. Reductions of up to 2 percent can be applied to states that spend 25 percent more than the national average.

For Georgia, this could bring large increases in funding for its elderly and disabled populations, where spending is about half the national average. Children already are funded above the national average – but not more than the 25 percent cutoff point. While funding for adults would decrease, the loss would be more than offset by increases in other areas.

| Medicaid Spending Per Enrollee (FY 2014) | ||||

| Elderly | Disabled | Adults | Children | |

| Georgia | $6,162 | $8,659 | $4,766 | $2,827 |

| U.S. average | $13,063 | $16,859 | $3,278 | $2,577 |

| GA % of U.S. average | 47% | 51% | 145% | 110% |

Source: Kaiser Family Foundation

Over time, this could benefit Georgia’s federal funding significantly.

Much of the current debate on Medicaid funding is related to the Senate’s proposal to reduce the Medicaid growth rate to the rate of inflation in 2025. Ahead of that, both chambers’ proposals would increase the grants by a combination of the medical inflation rate plus 1 percent for the disabled and elderly and the medical inflation rate for all others.

The Congressional Budget Office projects that the medical rate of inflation will be about 1.6 percent a year higher than the regular inflation rate. Even though the House and Senate are likely to compromise somewhere in the middle, authorizing the increase of up to 2 percent a year for low-spending states more than offsets the lower rate of inflation.

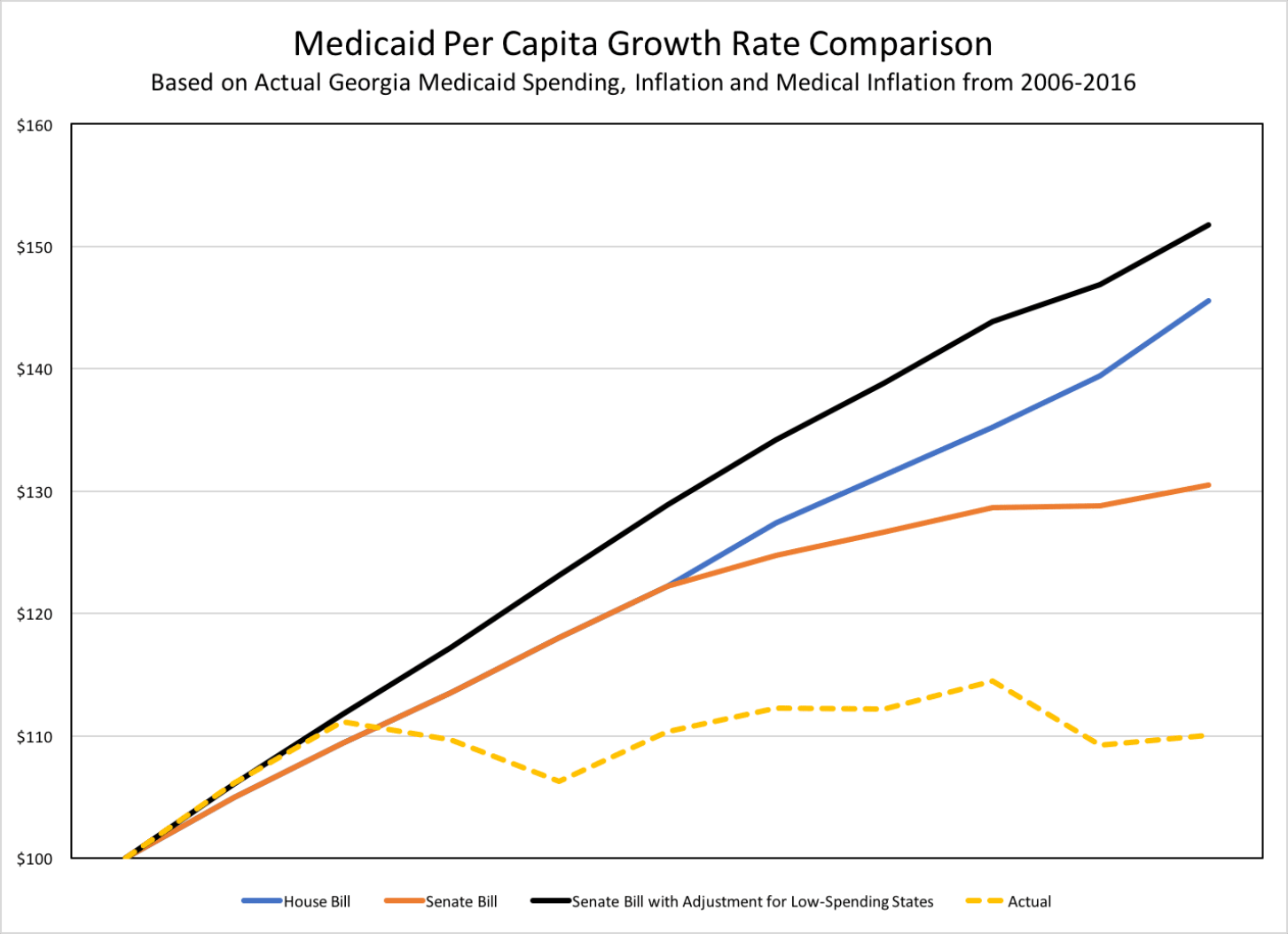

The chart below examines how a base amount of $100 in funding would change over 10 years under the various assumptions. (The growth rates were based on actual data from 2006 to 2016 and applied based on House and Senate proposals.)

Both chambers’ growth rates are the same for the first five years, with the Senate growing at a slower rate thereafter. The top line reflects the Senate growth rate with adjustments made based on Georgia’s spending levels relative to the national average. After these adjustments, the Senate growth rate results in more than 50 percent growth in 10 years compared to Georgia’s actual per-capita Medicaid spending growth of only 10 percent over the same period.

Both chambers’ growth rates are the same for the first five years, with the Senate growing at a slower rate thereafter. The top line reflects the Senate growth rate with adjustments made based on Georgia’s spending levels relative to the national average. After these adjustments, the Senate growth rate results in more than 50 percent growth in 10 years compared to Georgia’s actual per-capita Medicaid spending growth of only 10 percent over the same period.

This Senate provision needs one more change: These adjustments should be mandatory. Currently, the changes are discretionary and the cost savings from reductions in high-spending states must offset increases in low-spending states, bringing politics into the mix.

States need budgetary certainty, not empty promises. With this change, Congress can finally put a major entitlement program on a budget – one that brings fairness to all states.

Kelly McCutchen is President of the Georgia Public Policy Foundation, an independent, nonprofit think tank that proposes market-oriented approaches to public policy to improve the lives of Georgians. Nothing written here is to be construed as necessarily reflecting the view of the Georgia Public Policy Foundation or as an attempt to aid or hinder the passage of any bill before the U.S. Congress or the Georgia Legislature.

© Georgia Public Policy Foundation (July 7, 2017). Permission to reprint in whole or in part is hereby granted, provided the author and his affiliations are cited.

By Kelly McCutchen

As Congress returns next week from its Independence Day recess, health care will be front and center. Amid the noise from special interest groups drowning out substantive debate, one proposal that could enormously benefit Georgia has gone unnoticed.

The current U.S. Senate proposal, like the House version, introduces Medicaid per-capita block grants in 2020. Per-capita block grants have at one time or another been supported by both Democrats and Republicans. Putting Medicaid spending on a budget delights fiscal conservatives and deficit hawks.

As opposed to a traditional block grant, funding would adjust up and down based on the number of enrollees in the program. This protects states from surging rolls during a recession while saving federal and state money when individuals leave the program.

Unfortunately for Georgia, the initial block grant funding levels are based on historical spending, an unfair approach given the large differences in funding among the states.

Take New York. That state spends more than three times as much on disabled and elderly Medicaid recipients than does Georgia. The House legislation as passed would perpetuate this inequity.

One solution the Georgia Public Policy Foundation has proposed is what statisticians call “reversion to the mean:” Over time, high-spending states would receive less and low spending states would get more, moving all states closer to the national average. This could be accomplished by adjusting the growth rates on the block grants to avoid abrupt changes in funding.

That is exactly what the Senate has done. The latest Senate bill (page 64) authorizes the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services to increase state block grants by up to 2 percent per year in states spending less than 25 percent of the national average. Reductions of up to 2 percent can be applied to states that spend 25 percent more than the national average.

For Georgia, this could bring large increases in funding for its elderly and disabled populations, where spending is about half the national average. Children already are funded above the national average – but not more than the 25 percent cutoff point. While funding for adults would decrease, the loss would be more than offset by increases in other areas.

| Medicaid Spending Per Enrollee (FY 2014) | ||||

| Elderly | Disabled | Adults | Children | |

| Georgia | $6,162 | $8,659 | $4,766 | $2,827 |

| U.S. average | $13,063 | $16,859 | $3,278 | $2,577 |

| GA % of U.S. average | 47% | 51% | 145% | 110% |

Source: Kaiser Family Foundation

Over time, this could benefit Georgia’s federal funding significantly.

Much of the current debate on Medicaid funding is related to the Senate’s proposal to reduce the Medicaid growth rate to the rate of inflation in 2025. Ahead of that, both chambers’ proposals would increase the grants by a combination of the medical inflation rate plus 1 percent for the disabled and elderly and the medical inflation rate for all others.

The Congressional Budget Office projects that the medical rate of inflation will be about 1.6 percent a year higher than the regular inflation rate. Even though the House and Senate are likely to compromise somewhere in the middle, authorizing the increase of up to 2 percent a year for low-spending states more than offsets the lower rate of inflation.

The chart below examines how a base amount of $100 in funding would change over 10 years under the various assumptions. (The growth rates were based on actual data from 2006 to 2016 and applied based on House and Senate proposals.)

Both chambers’ growth rates are the same for the first five years, with the Senate growing at a slower rate thereafter. The top line reflects the Senate growth rate with adjustments made based on Georgia’s spending levels relative to the national average. After these adjustments, the Senate growth rate results in more than 50 percent growth in 10 years compared to Georgia’s actual per-capita Medicaid spending growth of only 10 percent over the same period.

Both chambers’ growth rates are the same for the first five years, with the Senate growing at a slower rate thereafter. The top line reflects the Senate growth rate with adjustments made based on Georgia’s spending levels relative to the national average. After these adjustments, the Senate growth rate results in more than 50 percent growth in 10 years compared to Georgia’s actual per-capita Medicaid spending growth of only 10 percent over the same period.

This Senate provision needs one more change: These adjustments should be mandatory. Currently, the changes are discretionary and the cost savings from reductions in high-spending states must offset increases in low-spending states, bringing politics into the mix.

States need budgetary certainty, not empty promises. With this change, Congress can finally put a major entitlement program on a budget – one that brings fairness to all states.

Kelly McCutchen is President of the Georgia Public Policy Foundation, an independent, nonprofit think tank that proposes market-oriented approaches to public policy to improve the lives of Georgians. Nothing written here is to be construed as necessarily reflecting the view of the Georgia Public Policy Foundation or as an attempt to aid or hinder the passage of any bill before the U.S. Congress or the Georgia Legislature.

© Georgia Public Policy Foundation (July 7, 2017). Permission to reprint in whole or in part is hereby granted, provided the author and his affiliations are cited.