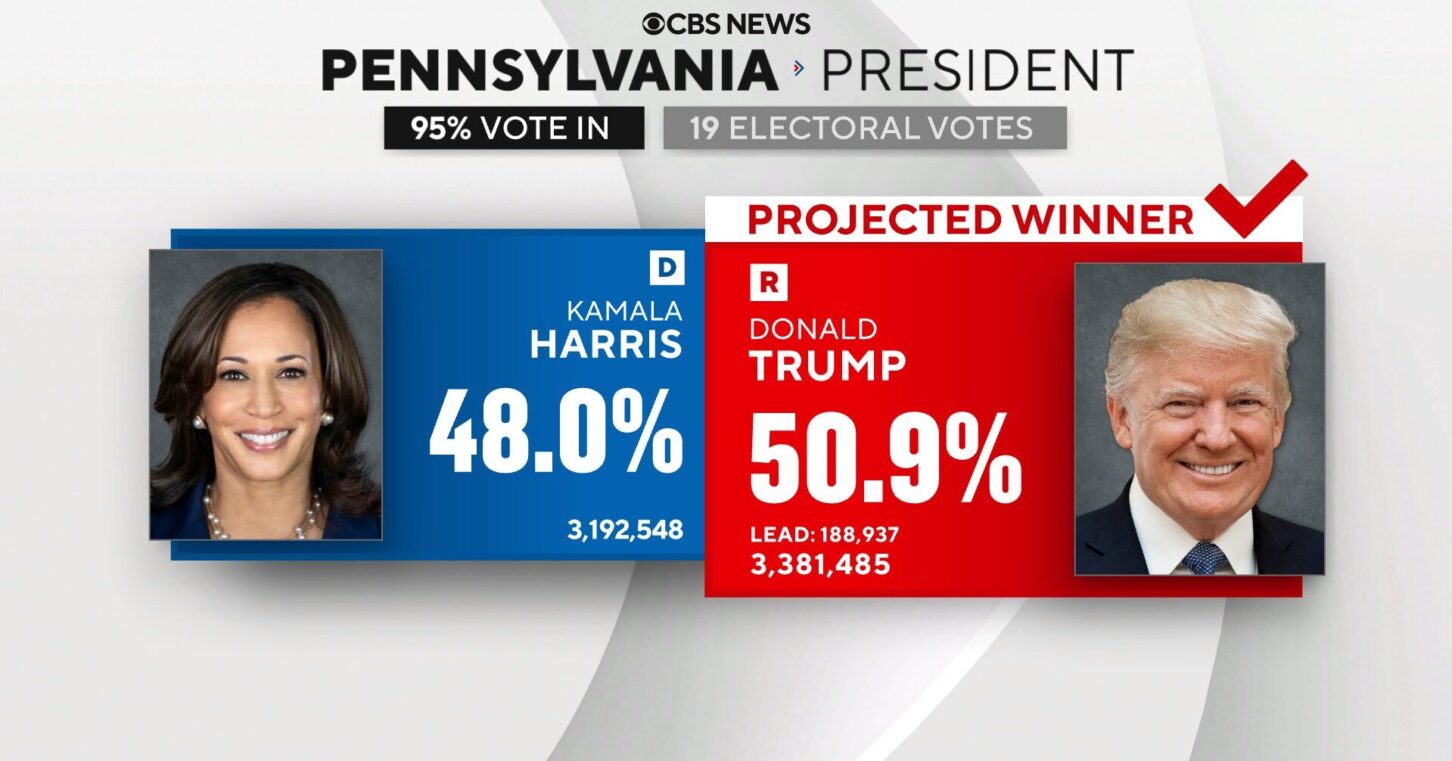

Every four years, we Americans reacquaint ourselves with our unique institution, the Electoral College. Although it appears Donald Trump has re-won the presidency with both an electoral and a popular majority, it’s worth reminding ourselves why this system exists.

But before that, here is a brief refresher on the Electoral College. Each state is apportioned “electors” based on its congressional delegation. Georgia, with 14 House members plus two senators, gets 16. These electors are technically the people you select when you vote for president.

The slate of electors pledged to the winning party’s candidate casts its votes in the Electoral College during a meeting in their state. This year it’s scheduled for Dec. 17.

The Founding Fathers designed this whole process to protect against “cabal, intrigue and corruption,” as Alexander Hamilton wrote in Federalist No. 68. Hamilton referred directly to foreign interference, but he also emphasized the benefits of decentralizing the vote:

“Talents for low intrigue, and the little arts of popularity, may alone suffice to elevate a man to the first honors in a single state,” he wrote, “but it will require other talents, and a different kind of merit, to establish him in the esteem and confidence of the whole Union, or of so considerable a portion of it as would be necessary to make him a successful candidate for the distinguished office of President of the United States.”

There are other reasons to support the Electoral College. Some of them were enumerated in a recent series of blog posts by Trent England, executive director of Save Our States.

First, the Electoral College keeps any disputes quarantined within a single state. “The Electoral College,” England writes, “uses state boundaries like the watertight bulkheads on an ocean liner. Disputes, whether over mistakes or fraud and whether well founded or not, are contained within individual states.”

Recall the firestorm in Georgia after the 2020 election, or Florida’s “hanging chad” debacle of 2000. While each incident sparked national interest, at least it didn’t prompt the other 49 states to recount their own votes. Imagine the potential for mischief if suddenly every state reopened its own contest with an incentive to pad or whittle its margins.

Second, England notes that the logical next step of eliminating the Electoral College might be to federalize elections – creating an awful conflict of interest.

“(W)ho carries into execution the laws passed by Congress? Ah yes, the executive, led by the President of the United States,” he writes. “Federalizing control of elections means putting presidents in charge of presidential elections. With the Electoral College, that power is decentralized and kept far from the White House.”

Third, the Electoral College “often amplifies the popular vote result and bolsters the legitimacy of plurality winners,” England writes. While we tend to focus on the discrepancies between the electoral and popular votes in 2000 and 2016, these are rare. In 1992, 2008 and 2012, the Electoral College enhanced clarity by providing a larger margin than the popular vote. The same appears to be true this year.

Fourth, the Electoral College incentivizes national rather than regional coalitions. While the list of states considered “safe” for one party changes over time, consider Democrats’ current strength in New England and on the West Coast. If not for the need to win other electoral votes, Democrats might win a popular vote simply by “running up the score” in New York and California. Instead, Kamala Harris competed hard, if ultimately unsuccessfully, in Georgia and North Carolina.

Finally, England notes the Electoral College promotes trust in elections precisely because the closest states, or swing states, are so closely divided.

“When we have a close election, the result will come down to what happens in the most politically balanced states,” he writes, “which is very good, because those states are likely to have the most political accountability … in a balanced state, both parties are likely to have some power. This is much better – for accountability – than when one party has all the power.”

Systemic, constitutional questions are best answered by considering the full span of history, not just temporary hiccups. Whether you liked or disliked the result this week, Americans are better off with our time-tested system.