Economic indicators are not consistently favorable to the South, but the net movement of Americans southward for a half-century is indicative of a land of opportunity.

By Harold Brown

In the first half of the 20th century, the South lost many of its people to northern and western migration. Much of the loss was due to “The Great Migration,” demographers’ term for the movement of black Americans north in search of better jobs and greater freedom.

From the 1910s to the 1950s about 4.5 million blacks moved away from the South, along with about the same number of whites. The percentage of blacks living outside the South increased from about 10 percent in the first two decades of the century to nearly half by 1970.

Georgia was right in the middle of the exodus. A University of Georgia professor was quoted in The Atlanta Constitution in 1939, saying “Of the 3,500,000 persons who have migrated to other states from the 11 southern states, one-fourth have migrated from Georgia.”

Little recent publicity has been given to domestic migration, but it has been more sweeping since the 1960s and, in several respects, opposite the first half of the 20th century.

Migration among states is as problematic (or advantageous) as international migration, though less recognized, and much less publicized – less noticed partly because we have become such a mobile society. Regional migration, though, is both a cause and result of economic and social changes. The term “Rust Belt,” for example, has been used to refer to the region where steel-related industry decreased, jobs were lost, and from which people migrated.

Of course, the strong historic migration trend has been westward. And since 1950 that trend has continued, with the nation’s population center shifting about 200 miles west, but also 90 miles south. Despite this trend, it was the 1970s before the combined census regions South and West became more populous than the combined Northeast and Midwest.

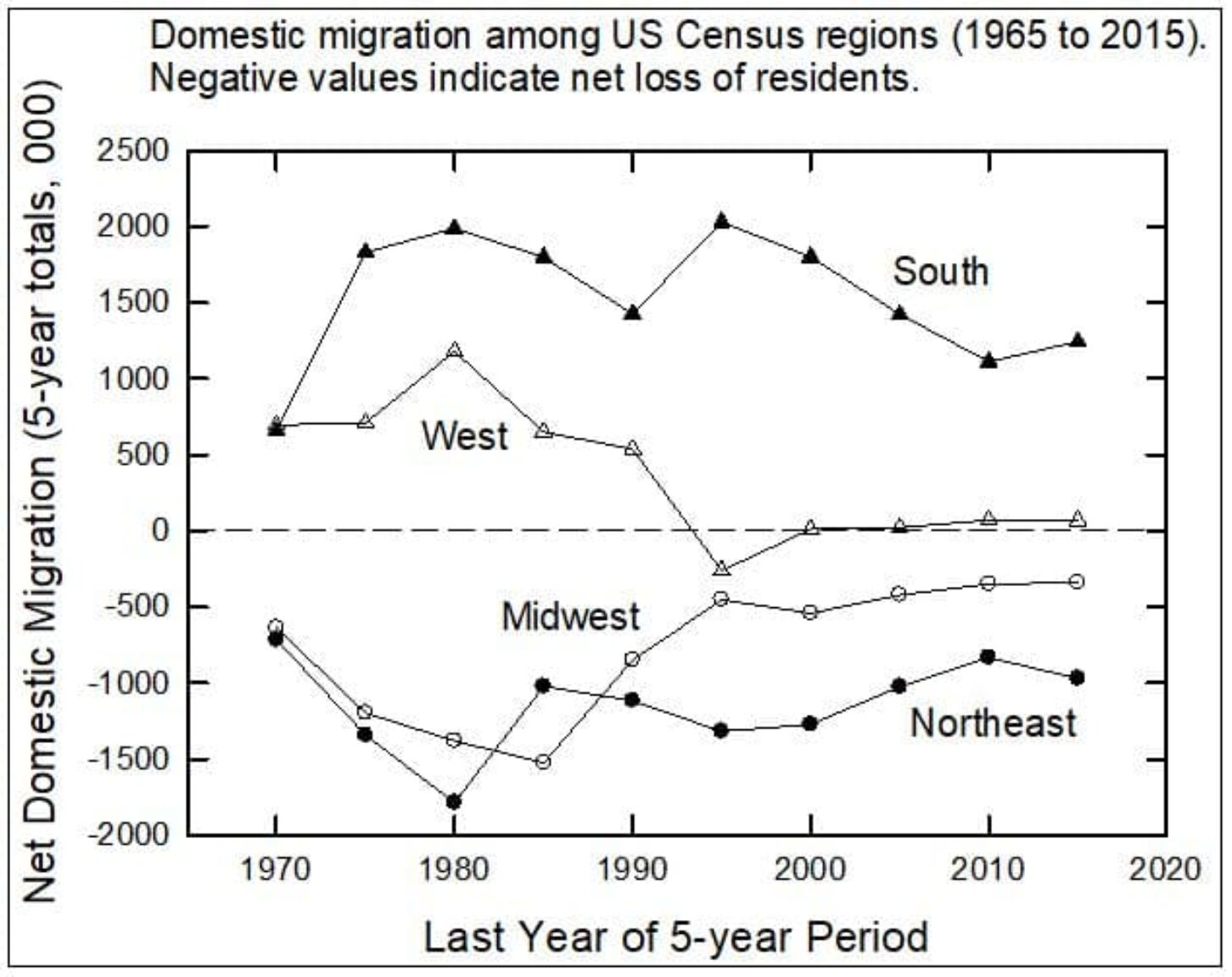

The Northeast and Midwest census regions, consisting of 21 states, had a net loss of 19 million domestic migrants since 1965 (up to 2015, see nearby chart). That’s about twice as many people as the South lost through migration in the first half of the 20th century. The migrants lost by the Northeast and Midwest since 1965 were, of course, gained by both the South and the West, but the South won 80 percent of the movers. Since 2000, the South received 86 percent of those migrants.

Whereas the West has received more domestic migrants than it lost throughout the 20th century, the net gain has dropped to near zero since the mid-1990s. On the other hand, the Midwest has lost fewer since then.

The loss of domestic migrants by the Northeast and Midwest does not mean their populations did not grow. Immigration from abroad since 1975 offset their loss of domestic migrants, or nearly so. In addition, natural increase (births minus deaths) of the Northeast population since 1975 was 8.8 million, and for the Midwest region 14.1 million.

The South has also excelled in population growth by natural increase and immigration. The South’s natural increase since 1975 was 1.5 million more than in the Northeast and Midwest combined, and 3 million more than in the West region. Foreign immigration to the South during this period was similar to the West (17-18 million), and to the combined gain by the Northeast and Midwest.

Consequently, the South’s population grew by nearly 55 million since 1975, more than three times the rise in the combined Northeast and Midwest, and 15 million more than the West.

Its economy has prospered, too. The South’s share of the national GDP increased from 27.5 percent in 1970 to 34.5 percent in 2017. Part of the reason may be lower labor costs. Employer cost per hour worked by employees (including wages and benefits) is the lowest in the country, $10 less than in the Northeast and $7 below the Midwest.

The labor force is also outgrowing that of the Northeast and Midwest, whose labor force increased 10-15 percent since 1990, while the South’s increased almost 40 percent, similar to that of the West Region.

Likewise, the number of business establishments increased more in the South since 1990 than anywhere else. Aggregate personal income tripled in the Northeast and Midwest since 1990 but quadrupled in the South and West. Individual personal income in the South, though just over 50 percent of the national average in the 1930s, has been nearly up to that average (about 95 percent) since 2000.

Economic indicators are not consistently favorable to the South, but the net movement of Americans southward for a half-century is indicative of a land of opportunity.

University of Georgia Professor Emeritus Harold Brown is a Senior Fellow with the Georgia Public Policy Foundation and author of, “The Greening of Georgia: The Improvement of the Environment in the Twentieth Century.” The Georgia Public Policy Foundation is an independent, nonprofit, state-focused think tank that proposes market-oriented approaches to public policy to improve the lives of Georgians. Nothing written here is to be construed as necessarily reflecting the views of the Georgia Public Policy Foundation or as an attempt to aid or hinder the passage of any bill before the U.S. Congress or the Georgia Legislature.

© Georgia Public Policy Foundation (August 10, 2018). Permission to reprint in whole or in part is hereby granted, provided the author and his affiliations are cited.

By Harold Brown

In the first half of the 20th century, the South lost many of its people to northern and western migration. Much of the loss was due to “The Great Migration,” demographers’ term for the movement of black Americans north in search of better jobs and greater freedom.

From the 1910s to the 1950s about 4.5 million blacks moved away from the South, along with about the same number of whites. The percentage of blacks living outside the South increased from about 10 percent in the first two decades of the century to nearly half by 1970.

Georgia was right in the middle of the exodus. A University of Georgia professor was quoted in The Atlanta Constitution in 1939, saying “Of the 3,500,000 persons who have migrated to other states from the 11 southern states, one-fourth have migrated from Georgia.”

Little recent publicity has been given to domestic migration, but it has been more sweeping since the 1960s and, in several respects, opposite the first half of the 20th century.

Migration among states is as problematic (or advantageous) as international migration, though less recognized, and much less publicized – less noticed partly because we have become such a mobile society. Regional migration, though, is both a cause and result of economic and social changes. The term “Rust Belt,” for example, has been used to refer to the region where steel-related industry decreased, jobs were lost, and from which people migrated.

Of course, the strong historic migration trend has been westward. And since 1950 that trend has continued, with the nation’s population center shifting about 200 miles west, but also 90 miles south. Despite this trend, it was the 1970s before the combined census regions South and West became more populous than the combined Northeast and Midwest.

The Northeast and Midwest census regions, consisting of 21 states, had a net loss of 19 million domestic migrants since 1965 (up to 2015, see nearby chart). That’s about twice as many people as the South lost through migration in the first half of the 20th century. The migrants lost by the Northeast and Midwest since 1965 were, of course, gained by both the South and the West, but the South won 80 percent of the movers. Since 2000, the South received 86 percent of those migrants.

Whereas the West has received more domestic migrants than it lost throughout the 20th century, the net gain has dropped to near zero since the mid-1990s. On the other hand, the Midwest has lost fewer since then.

The loss of domestic migrants by the Northeast and Midwest does not mean their populations did not grow. Immigration from abroad since 1975 offset their loss of domestic migrants, or nearly so. In addition, natural increase (births minus deaths) of the Northeast population since 1975 was 8.8 million, and for the Midwest region 14.1 million.

The South has also excelled in population growth by natural increase and immigration. The South’s natural increase since 1975 was 1.5 million more than in the Northeast and Midwest combined, and 3 million more than in the West region. Foreign immigration to the South during this period was similar to the West (17-18 million), and to the combined gain by the Northeast and Midwest.

Consequently, the South’s population grew by nearly 55 million since 1975, more than three times the rise in the combined Northeast and Midwest, and 15 million more than the West.

Its economy has prospered, too. The South’s share of the national GDP increased from 27.5 percent in 1970 to 34.5 percent in 2017. Part of the reason may be lower labor costs. Employer cost per hour worked by employees (including wages and benefits) is the lowest in the country, $10 less than in the Northeast and $7 below the Midwest.

The labor force is also outgrowing that of the Northeast and Midwest, whose labor force increased 10-15 percent since 1990, while the South’s increased almost 40 percent, similar to that of the West Region.

Likewise, the number of business establishments increased more in the South since 1990 than anywhere else. Aggregate personal income tripled in the Northeast and Midwest since 1990 but quadrupled in the South and West. Individual personal income in the South, though just over 50 percent of the national average in the 1930s, has been nearly up to that average (about 95 percent) since 2000.

Economic indicators are not consistently favorable to the South, but the net movement of Americans southward for a half-century is indicative of a land of opportunity.

University of Georgia Professor Emeritus Harold Brown is a Senior Fellow with the Georgia Public Policy Foundation and author of, “The Greening of Georgia: The Improvement of the Environment in the Twentieth Century.” The Georgia Public Policy Foundation is an independent, nonprofit, state-focused think tank that proposes market-oriented approaches to public policy to improve the lives of Georgians. Nothing written here is to be construed as necessarily reflecting the views of the Georgia Public Policy Foundation or as an attempt to aid or hinder the passage of any bill before the U.S. Congress or the Georgia Legislature.

© Georgia Public Policy Foundation (August 10, 2018). Permission to reprint in whole or in part is hereby granted, provided the author and his affiliations are cited.