The New Teacher Project (TNTP) is a national organization that “works with schools, districts and states to provide excellent teachers to the students who need them most and advance policies and practices that ensure effective teaching in every classroom.”

By Eric Wearne

The New Teacher Project (TNTP) is a national organization that “works with schools, districts and states to provide excellent teachers to the students who need them most and advance policies and practices that ensure effective teaching in every classroom.”

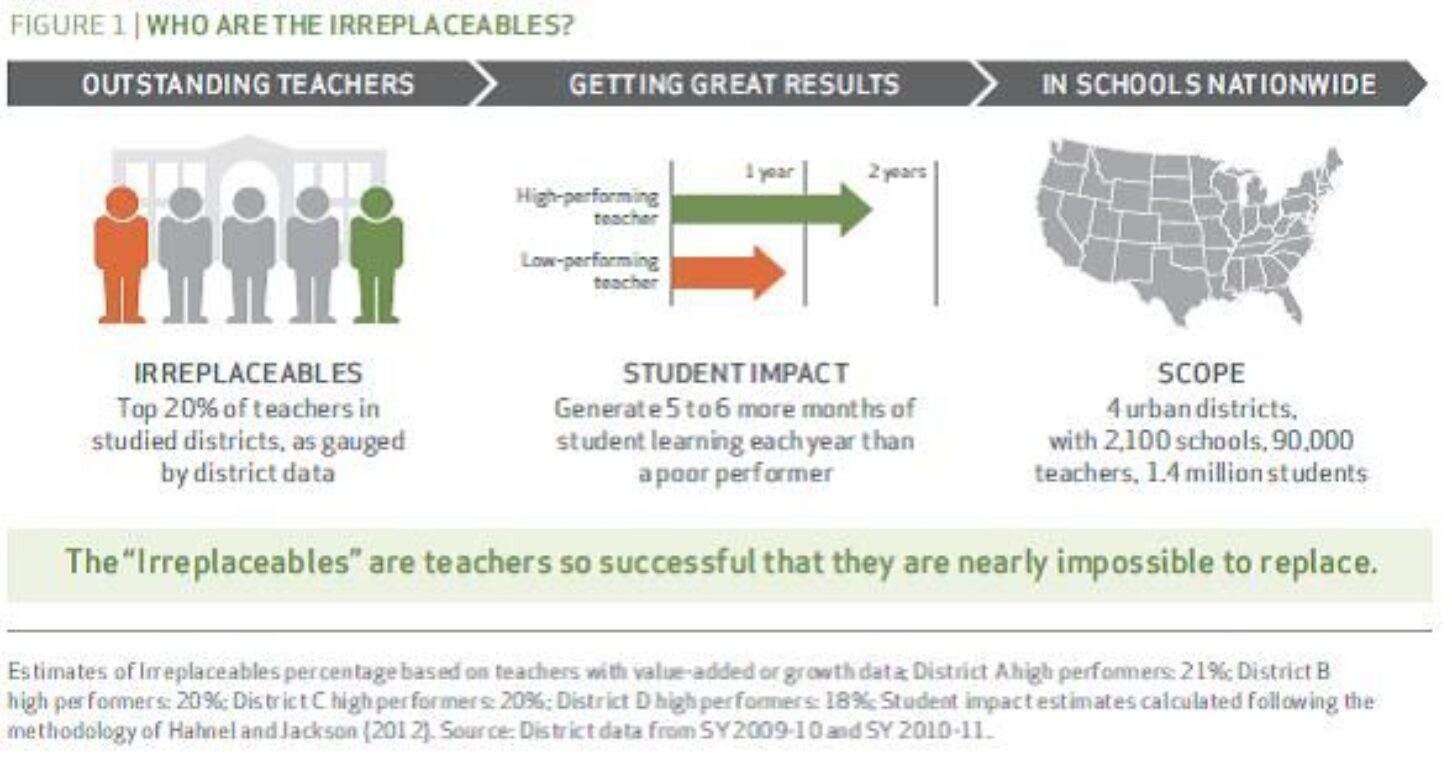

TNTP recently published a report called “The Irreplaceables,” which discusses the “real retention crisis in America’s urban schools.”* For the purposes of this report, TNTP defines “Irreplaceables” by looking at the value-added test data provided by four large urban school systems.

Those whose students gained 5-6 more months of learning each year compared to lower-performing teachers were deemed “Irreplaceable” – about 20 percent of the teachers in each of the school systems TNTP examined.

TNTP also interviewed teachers in these school systems. Combining value-added data with the interview data, they were able to identify three major reasons schools tend to lose their “irreplaceable” teachers:

- Principals make too little effort to retain Irreplacables or to remove low-performing teachers;

- Poor school cultures and working conditions drive away great teachers; and

- Policies give principals and district leaders few incentives to change their ways.

Other issues TNTP names are “meaningless evaluation systems,” “lockstep compensation systems,” and “lack of career pathways.” Ultimately, TNTP estimates that “approximately 10,000 Irreplaceables leave the 50 largest school districts across the country each year.” Even worse, according to TNTP:

Other issues TNTP names are “meaningless evaluation systems,” “lockstep compensation systems,” and “lack of career pathways.” Ultimately, TNTP estimates that “approximately 10,000 Irreplaceables leave the 50 largest school districts across the country each year.” Even worse, according to TNTP:

It’s not inevitable. Our findings suggest that Irreplacables usually leave for reasons that their school could have controlled. Less than 30 percent of those who planned to leave in the next three years said they were doing so primarily for personal reasons. More than half said they planned either to continue teaching at a nearby school or working in K-12 education. And more than 75 percent said they would have stayed at their school if their main issues for leaving were addressed.

All of this leads to severe limitations on educators’ and communities’ ability to turn around low-performing schools, and to a degradation of the teaching profession, as high-performers are valued no more than low-performers.

Helpfully, TNTP does offer concrete suggestions to improve the situation. Specifically, they call for school systems to:

- Make retention of Irreplacables a top priority; and

- Strengthen the teaching profession through higher expectations.

One example they cite from their interviews is that “70 percent of Irreplacables would take on an additional five students in exchange for a $7,500 raise.”

That example – finding a method to expose more students to the best teachers – hints at the one glaring omission in an otherwise excellent report. No mention is made of the potential for online and hybrid methods to help retain the Irreplacables, or to leverage their skills to help more students.

If America’s 50 largest urban districts are losing 10,000 teachers per year, as TNTP estimates, that is a huge problem, and calls for several responses. One is to improve retention policies, as is the focus of this report. Another would be to train more excellent teachers, though that’s calling for a pace that will be hard to reach or to maintain.

But probably the most scalable response would be to find ways to leverage these teachers’ abilities and get them in front of as many students as possible, even if it’s not always in person. Any good report, as this one is, sets up a path for “future research;” online learning as a method to retain the Irreplacables would be a fruitful one.

* It’s worth noting that the conventional wisdom that teachers leave the profession in droves within their first few years, at least in Georgia, is somewhat overwrought, as described in a 2010 report conducted for the Governor’s Office of Student Achievement by Ben Scafidi, using 10 years of actual Georgia educator employment data.

(Eric Wearne is a Georgia Public Policy Foundation Senior Fellow and Assistant Professor at the Georgia Gwinnett College School of Education. Previously he was Deputy Director of the Governor’s Office of Student Achievement.)

By Eric Wearne

The New Teacher Project (TNTP) is a national organization that “works with schools, districts and states to provide excellent teachers to the students who need them most and advance policies and practices that ensure effective teaching in every classroom.”

TNTP recently published a report called “The Irreplaceables,” which discusses the “real retention crisis in America’s urban schools.”* For the purposes of this report, TNTP defines “Irreplaceables” by looking at the value-added test data provided by four large urban school systems.

Those whose students gained 5-6 more months of learning each year compared to lower-performing teachers were deemed “Irreplaceable” – about 20 percent of the teachers in each of the school systems TNTP examined.

TNTP also interviewed teachers in these school systems. Combining value-added data with the interview data, they were able to identify three major reasons schools tend to lose their “irreplaceable” teachers:

- Principals make too little effort to retain Irreplacables or to remove low-performing teachers;

- Poor school cultures and working conditions drive away great teachers; and

- Policies give principals and district leaders few incentives to change their ways.

Other issues TNTP names are “meaningless evaluation systems,” “lockstep compensation systems,” and “lack of career pathways.” Ultimately, TNTP estimates that “approximately 10,000 Irreplaceables leave the 50 largest school districts across the country each year.” Even worse, according to TNTP:

Other issues TNTP names are “meaningless evaluation systems,” “lockstep compensation systems,” and “lack of career pathways.” Ultimately, TNTP estimates that “approximately 10,000 Irreplaceables leave the 50 largest school districts across the country each year.” Even worse, according to TNTP:

It’s not inevitable. Our findings suggest that Irreplacables usually leave for reasons that their school could have controlled. Less than 30 percent of those who planned to leave in the next three years said they were doing so primarily for personal reasons. More than half said they planned either to continue teaching at a nearby school or working in K-12 education. And more than 75 percent said they would have stayed at their school if their main issues for leaving were addressed.

All of this leads to severe limitations on educators’ and communities’ ability to turn around low-performing schools, and to a degradation of the teaching profession, as high-performers are valued no more than low-performers.

Helpfully, TNTP does offer concrete suggestions to improve the situation. Specifically, they call for school systems to:

- Make retention of Irreplacables a top priority; and

- Strengthen the teaching profession through higher expectations.

One example they cite from their interviews is that “70 percent of Irreplacables would take on an additional five students in exchange for a $7,500 raise.”

That example – finding a method to expose more students to the best teachers – hints at the one glaring omission in an otherwise excellent report. No mention is made of the potential for online and hybrid methods to help retain the Irreplacables, or to leverage their skills to help more students.

If America’s 50 largest urban districts are losing 10,000 teachers per year, as TNTP estimates, that is a huge problem, and calls for several responses. One is to improve retention policies, as is the focus of this report. Another would be to train more excellent teachers, though that’s calling for a pace that will be hard to reach or to maintain.

But probably the most scalable response would be to find ways to leverage these teachers’ abilities and get them in front of as many students as possible, even if it’s not always in person. Any good report, as this one is, sets up a path for “future research;” online learning as a method to retain the Irreplacables would be a fruitful one.

* It’s worth noting that the conventional wisdom that teachers leave the profession in droves within their first few years, at least in Georgia, is somewhat overwrought, as described in a 2010 report conducted for the Governor’s Office of Student Achievement by Ben Scafidi, using 10 years of actual Georgia educator employment data.

Eric Wearne is a Georgia Public Policy Foundation Senior Fellow and Assistant Professor at the Georgia Gwinnett College School of Education. Previously he was Deputy Director of the Governor’s Office of Student Achievement.