Transportation Tuesday, December 1, 2020: Policy, news and views driving transportation.

Gwinnett Transit Referendum Postmortem

By Dave Emanuel

When Gwinnett County voters defeated the county’s 2019 transit referendum, proponents blamed their loss on the referendum being on the ballot of a special election, which typically has low voter turnout. When a referendum for a revised plan was placed on the ballot for the November 2020 general election, however, the results were the same: defeat.

When Gwinnett County voters defeated the county’s 2019 transit referendum, proponents blamed their loss on the referendum being on the ballot of a special election, which typically has low voter turnout. When a referendum for a revised plan was placed on the ballot for the November 2020 general election, however, the results were the same: defeat.

The relatively narrow margin of defeat – 1,013 votes – does not tell the whole story. Of the 413,865 county voters who participated in the presidential election, only 398,041 voted on transit expansion. In other words, 5,824 voters could not decide how to vote or had no strong feelings either way. There’s no way to determine whether the results would be appreciably different had they voted, but what is clear is that 5,824 voters were not sold on the idea of paying a penny sales tax for 30 years to expand transit.

Supporters argued new options are desperately needed to reduce road congestion. Opponents saw the plan’s options as providing too little impact at too high a cost. In fact, both sides have valid points. But the most relevant question is, why, in spite of an aggressive “education” (sales) program, did the referendum fail?

First and foremost was the inclusion of a four-mile MARTA heavy rail extension. The estimated cost of $1.5 billion and a proposed time frame for completion of 20-30 years were decided turn-offs for many voters. Beyond that, MARTA’s checkered financial history – $2.2 billion in outstanding bonds and a reputation for poor service – loomed as additional reasons to vote no. Furthermore, MARTA’s existing system is hopelessly inadequate. The rail system in New York City has 426 stations. Boston has 148. Chicago has 145. Washington, D.C., has 91 and Denver has 78. MARTA offers a mere 38 stations.

First and foremost was the inclusion of a four-mile MARTA heavy rail extension. The estimated cost of $1.5 billion and a proposed time frame for completion of 20-30 years were decided turn-offs for many voters. Beyond that, MARTA’s checkered financial history – $2.2 billion in outstanding bonds and a reputation for poor service – loomed as additional reasons to vote no. Furthermore, MARTA’s existing system is hopelessly inadequate. The rail system in New York City has 426 stations. Boston has 148. Chicago has 145. Washington, D.C., has 91 and Denver has 78. MARTA offers a mere 38 stations.

Adding a station in Norcross may make it easier for Gwinnett residents on the county’s southwestern edge to board a MARTA train, but it will still take a long walk (10 minutes) or ride-hail to reach many destinations. In essence, adding the station simply gives more people access to a system that doesn’t take them where they want to go.

Eliminating heavy rail from future transit plans may lead to a successful referendum. The premise that transit will significantly reduce traffic and congestion, however, may continue to be a tough sell.

One claimed benefit of an expanded transit system is reduced traffic on county roads. Another is that it will inspire economic development. Those two claims are in conflict with each other. Economic development brings more people to the county; not all newcomers will use transit and the net effect could easily be more traffic. New York City, with the nation’s most robust public transit system, has its streets continually clogged with cars.

That isn’t to imply Gwinnett should scrap plans for expanded transit. It needs a fresh approach to education and a graduated plan that demonstrates transit’s advantages. To date, transit proponents have provided no evidence expanded transit will be used by enough people to justify its cost.

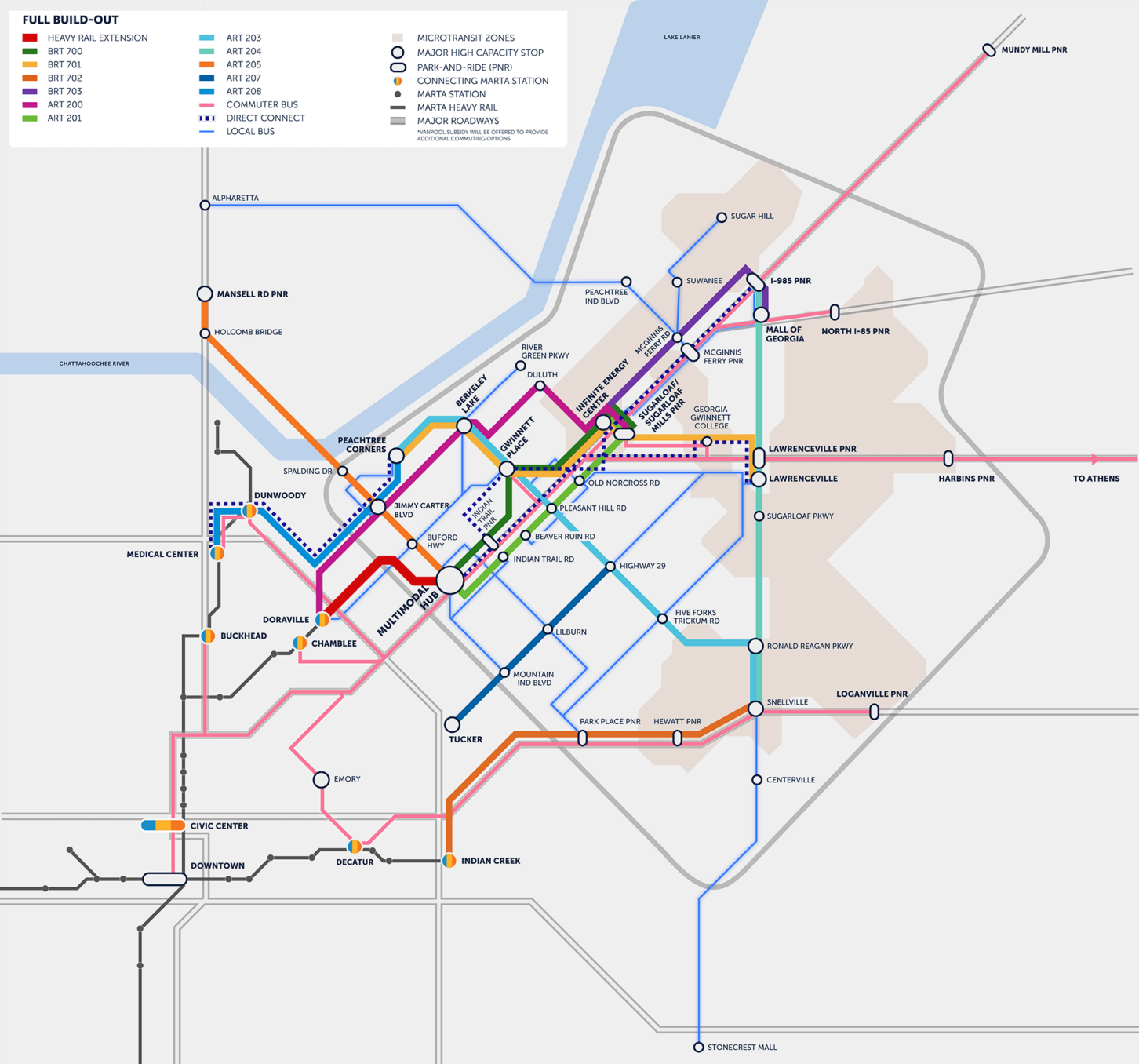

Consequently, they have yet to demonstrate that billions of dollars in sales tax revenue will reduce road congestion. The “education” forum website told voters why the referendum was on the ballot, listed the differences between the 2019 and 2020 versions, and included a map of the 80-plus projects when completed. Nowhere did it list information about projected ridership or reduced congestion.

That leaves unanswered the question of what taxpayers will receive for multiple billions of dollars in expenses. Will these transportation projects deliver tangible improvement in mobility, or will the result be a fleet of empty vehicles driving around?

Dave Emanuel is Mayor Pro Tem of Snellville.

© Georgia Public Policy Foundation (December 1, 2020). Permission to reprint in whole or in part is hereby granted, provided the author and his affiliations are cited.