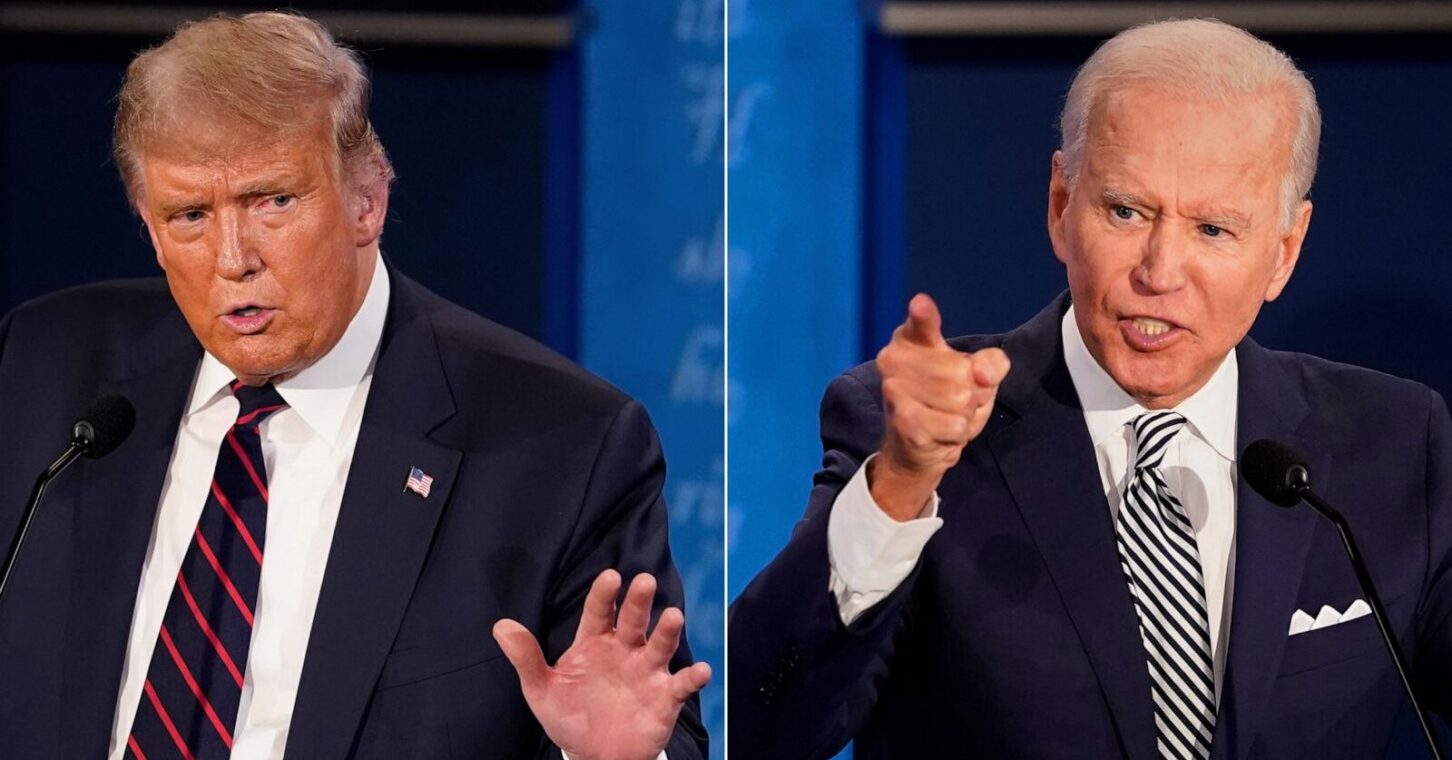

Georgia is already a focus this presidential election year. But the nation’s eyes will be squarely on us this week as President Joe Biden and former President Donald Trump hold their first debate in Atlanta.

The stakes are always high for such showdowns, but this one feels particularly paramount. So far, the candidates have agreed to only one other debate. In a recent appearance on CNN, which will host the debate, Democratic political analyst Van Jones went so far as to call it “the entire election.”

“Because, if Biden goes out there and messes up, it’s game over,” Jones explained. “If he walks out there, and a week later he’s lower in the polls, it’s panic in the party. But if he goes in there and he can handle himself against Donald Trump – a runaway train, a locomotive, a raging bull – then this guy deserves another shot to be president, because that is tough.”

Some of that talk is standard political gamesmanship: Set expectations low for your guy and high for the opponent, so that even a mediocre performance can be spun as a win. But Jones’ comments also highlight the angst with which many Democrats regard Biden’s candidacy.

I’d like to tell you that such high stakes will make for great substance. But I doubt it.

Take the most important long-term problem our country faces: the national debt. Our ability to tackle every other problem we face – from our porous southern border, to our many enemies around the world, to our various domestic challenges – hinges on our financial wherewithal. And after decades of pretending we’re fiscally invincible, we’re facing something akin to our fiscal mortality.

When this year’s budget closes on Sept. 30, with an annual deficit approaching $2 trillion, we will have added more than $10 trillion of debt during the eight-year watch of the two men on the debate stage.

That’s roughly the same amount as we added – total – between 1923 and 2001. And yes, that’s adjusted for inflation.

So both men are probably reluctant to broach this subject. The political precariousness is further explained by an analysis of federal spending the Cato Institute published earlier this year.

“The largest type of spending in 2023,” per the Cato analysis, “was transfers ($3.19 trillion), followed by aid to the states ($1.15 trillion), interest ($0.95 trillion), purchases ($0.84 trillion), and worker compensation ($0.56 trillion).”

Transfers include Social Security, Medicare and welfare such as food stamps, while aid to the states includes subsidies for Medicaid, public schools and highway construction. Combined, they are what Cato calls “the redistribution part of the budget.” Purchases and compensation are what Cato calls “the production part of the budget”: actual operations such as national defense and national parks.

When making interest payments on the debt costs more than either buying things for what the government does or paying people to do those things, we have a major problem. When redistribution dwarfs both, we have an intractable problem.

That’s why talking about balancing the federal budget by reducing purchases or employee headcount is ludicrous. Washington could have gone this whole year without buying anything or paying any employees, and it still would have run a larger budget deficit than in any single year between the end of World War II and the beginning of the Great Recession.

It’s all about redistribution. And the redistribution budget is large because it’s popular. Social Security may run out of money and require sharp, mandatory cuts to beneficiaries in less than a decade, but neither Biden nor Trump will propose reforms because it would hurt them politically.

To some extent, that’s on them: Leaders are supposed to tell people the truth, even when it hurts. Perhaps to a larger extent, it’s on us. We ought to want leaders to tell us the truth, even when we don’t like it.

Regardless of the politics, facts are stubborn things. We’ll have to face them sooner or later.