Results from the first three Georgia counties to restore food stamp time limits.

By Benita M. Dodd

August marks the 20th anniversary of the transformative Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act. This bipartisan welfare reform legislation signed by President Bill Clinton on August 22, 1996, dramatically transformed the nation’s welfare system, implementing strong welfare-to-work requirements and incentivizing states to transition welfare recipients into work.

The law, which created Temporary Assistance for Needy Families and replaced the 61-year-old Aid to Families with Dependent Children, also implemented stricter food stamp regulations. Those included time limits for some recipients and a lifetime ban for drug felons, which states could opt out of. (Wisely, Georgia finally opted out this year, with Gov. Nathan Deal signing criminal justice reform legislation that allows drug felons to receive food stamps upon their release.)

The 1996 law allows states to suspend the time limit in areas with high unemployment; Georgia is one of 22 states that waived the time limit during the economic downturn. With the economic turnaround, states that waived time limits for aid to low-income individuals through the federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) – “food stamps”– have begun to reinstate those time limits.

Beginning in 2016, Gwinnett, Hall and Cobb counties became the first three Georgia counties to restore SNAP time limits for able-bodied adults without dependents – those ages 18-49 with no dependents and no disabilities. They are only allowed to receive SNAP benefits for three months in three years unless they meet work requirements.

To continue to receive food stamps beyond the time limit, these individuals must work at least 80 hours per month, participate in qualifying education and training, or participate in “workfare” – unpaid work through a special state-approved program. For workfare, the amount of time worked depends on the amount of benefits received each month. They can also participate in a SNAP employment and training program.

How has the end of the waiver affected the SNAP rolls in these three counties? According to the Division of Family and Children Services, 6,102 able-bodied adults without disabilities were receiving food stamps when the counties’ waiver ended in January. By April, when the three-month deadline took effect, that number had shrunk to 2,590, a whopping 58 percent decrease.

Even accounting for an uptick in the job market or additional recipients replacing those who dropped off, the decline is impressive. Gwinnett County saw a 64 percent drop in recipients in this category; Cobb saw a 56 percent decline and Hall saw a 37 percent decline. The decline continued in May: a remarkable 60 percent decline over January’s total.

For comparison: Gwinnett’s total SNAP count was 34,155 in January; that dropped to 31,767 in April. Of those 2,388 individuals, 1,657 were from the able-bodied, time-limited population. The total SNAP decline in Gwinnett was 7 percent. For the same period, Fulton saw a SNAP decline of less than 3 percent, Clayton’s dropped less than 5 percent decline and Bibb saw a 2 percent decline.

Why is this important? In 2017, another 21 Georgia counties will end the recession-related waiver on food stamps. Ending welfare assistance is not just about saving taxpayer dollars, although that is always welcome. The goal must be to focus aid on those who truly need help and restore the dignity of work to able-bodied adults. Reducing dependency and promoting economic opportunity help end the cycle of poverty, reinforce the temporary nature of assistance and encourage personal responsibility.

In October 2015, U.S. Rep. Tom Price of Georgia chaired a House Budget Committee hearing on poverty, “Restoring the Trust for America’s Most Vulnerable.” Larry Woods, who heads the Winston-Salem Housing Authority* and is a product of public housing, bemoaned the low expectations this nation has of welfare recipients:

Our current system is broken, plain and simple. And it’s broken because our approach is flawed. Representatives, it’s not about throwing more money at this problem. It’s not about pulling money away from this problem. It’s about implementing policies that actually provide a positive exit strategy for getting people out of the safety net. Right now, there is no exit strategy. We have spent much of our time trying to make sure that the net is there but we’ve lost focus on what happens next when someone enters that system. We are simply warehousing people in our programs; there’s no focus on getting people in, up and out. Our focus has been exclusively on making sure people get in; we must help policymakers and the program’s output for its effectiveness. We must hold individual beneficiaries of these services accountable as well.

We couldn’t have said it better ourselves.

*This commentary has been corrected to show that Larry Woods is head of the Winston-Salem Housing Authority. The original version incorrectly stated he is head of the Raleigh-Durham Housing Authority.

Benita M. Dodd is vice president of the Georgia Public Policy Foundation, an independent think tank that proposes market-oriented approaches to public policy to improve the lives of Georgians. Nothing written here is to be construed as necessarily reflecting the view of the Georgia Public Policy Foundation or as an attempt to aid or hinder the passage of any bill before the U.S. Congress or the Georgia Legislature.

© Georgia Public Policy Foundation (August 12, 2016). Permission to reprint in whole or in part is hereby granted, provided the author and her affiliations are cited.

By Benita M. Dodd

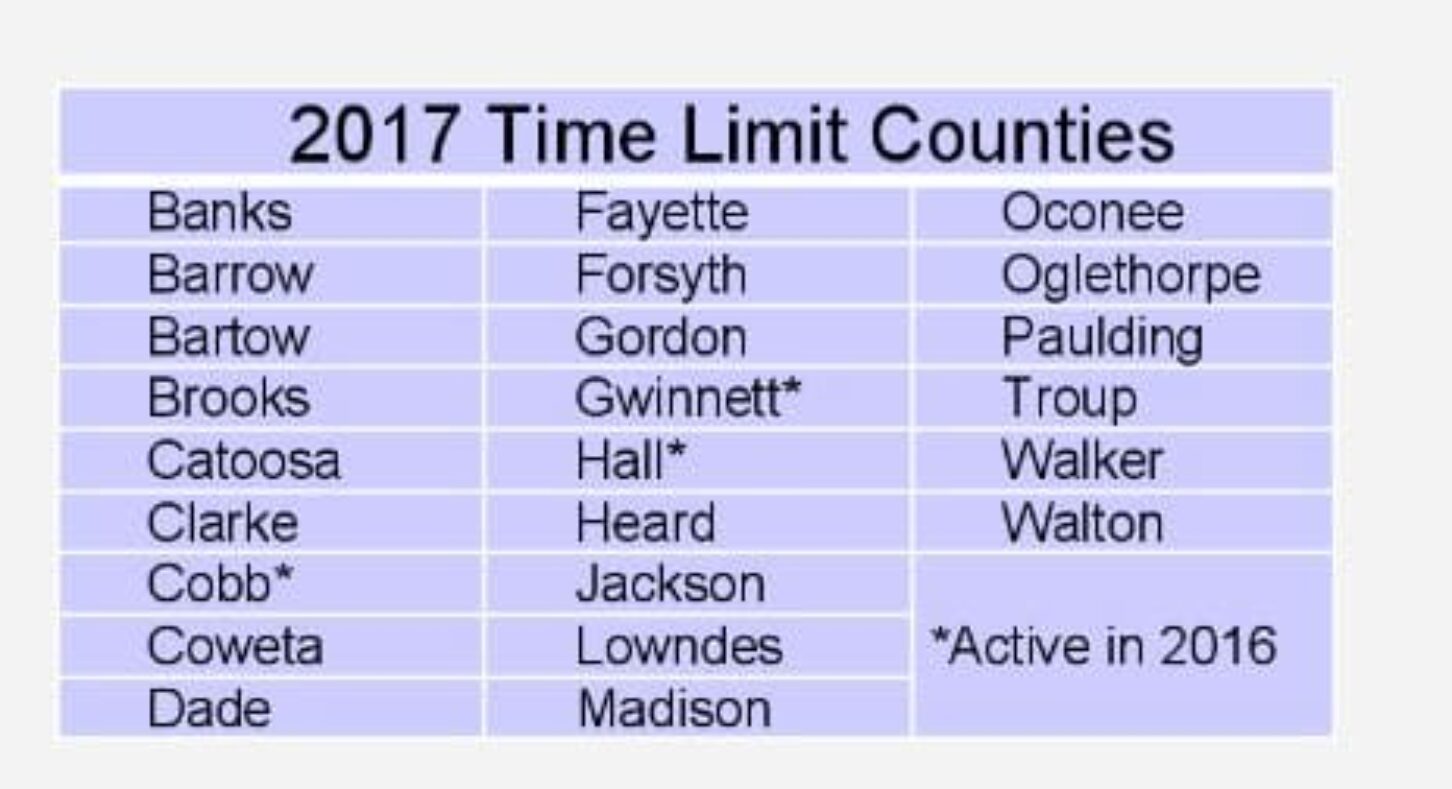

Twenty-one more Georgia counties will reinstate food stamp time limits in 2017 for able-bodied adults without dependents, according to the Division of Family and Children Services.

BENITA DODD

August marks the 20th anniversary of the transformative Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act. This bipartisan welfare reform legislation signed by President Bill Clinton on August 22, 1996, dramatically transformed the nation’s welfare system, implementing strong welfare-to-work requirements and incentivizing states to transition welfare recipients into work.

The law, which created Temporary Assistance for Needy Families and replaced the 61-year-old Aid to Families with Dependent Children, also implemented stricter food stamp regulations. Those included time limits for some recipients and a lifetime ban for drug felons, which states could opt out of. (Wisely, Georgia finally opted out this year, with Gov. Nathan Deal signing criminal justice reform legislation that allows drug felons to receive food stamps upon their release.)

The 1996 law allows states to suspend the time limit in areas with high unemployment; Georgia is one of 22 states that waived the time limit during the economic downturn. With the economic turnaround, states that waived time limits for aid to low-income individuals through the federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) – “food stamps”– have begun to reinstate those time limits.

Beginning in 2016, Gwinnett, Hall and Cobb counties became the first three Georgia counties to restore SNAP time limits for able-bodied adults without dependents – those ages 18-49 with no dependents and no disabilities. They are only allowed to receive SNAP benefits for three months in three years unless they meet work requirements.

To continue to receive food stamps beyond the time limit, these individuals must work at least 80 hours per month, participate in qualifying education and training, or participate in “workfare” – unpaid work through a special state-approved program. For workfare, the amount of time worked depends on the amount of benefits received each month. They can also participate in a SNAP employment and training program.

How has the end of the waiver affected the SNAP rolls in these three counties? According to the Division of Family and Children Services, 6,102 able-bodied adults without disabilities were receiving food stamps when the counties’ waiver ended in January. By April, when the three-month deadline took effect, that number had shrunk to 2,590, a whopping 58 percent decrease.

Even accounting for an uptick in the job market or additional recipients replacing those who dropped off, the decline is impressive. Gwinnett County saw a 64 percent drop in recipients in this category; Cobb saw a 56 percent decline and Hall saw a 37 percent decline. The decline continued in May: a remarkable 60 percent decline over January’s total.

For comparison: Gwinnett’s total SNAP count was 34,155 in January; that dropped to 31,767 in April. Of those 2,388 individuals, 1,657 were from the able-bodied, time-limited population. The total SNAP decline in Gwinnett was 7 percent. For the same period, Fulton saw a SNAP decline of less than 3 percent, Clayton’s dropped less than 5 percent decline and Bibb saw a 2 percent decline.

Why is this important? In 2017, another 21 Georgia counties will end the recession-related waiver on food stamps. Ending welfare assistance is not just about saving taxpayer dollars, although that is always welcome. The goal must be to focus aid on those who truly need help and restore the dignity of work to able-bodied adults. Reducing dependency and promoting economic opportunity help end the cycle of poverty, reinforce the temporary nature of assistance and encourage personal responsibility.

In October 2015, U.S. Rep. Tom Price of Georgia chaired a House Budget Committee hearing on poverty, “Restoring the Trust for America’s Most Vulnerable.” Larry Woods, who heads the Winston-Salem Housing Authority* and is a product of public housing, bemoaned the low expectations this nation has of welfare recipients:

Our current system is broken, plain and simple. And it’s broken because our approach is flawed. Representatives, it’s not about throwing more money at this problem. It’s not about pulling money away from this problem. It’s about implementing policies that actually provide a positive exit strategy for getting people out of the safety net. Right now, there is no exit strategy. We have spent much of our time trying to make sure that the net is there but we’ve lost focus on what happens next when someone enters that system. We are simply warehousing people in our programs; there’s no focus on getting people in, up and out. Our focus has been exclusively on making sure people get in; we must help policymakers and the program’s output for its effectiveness. We must hold individual beneficiaries of these services accountable as well.

We couldn’t have said it better ourselves.

*This commentary has been corrected to show that Larry Woods is head of the Winston-Salem Housing Authority. The original version incorrectly stated he is head of the Raleigh-Durham Housing Authority.

Benita M. Dodd is vice president of the Georgia Public Policy Foundation, an independent think tank that proposes market-oriented approaches to public policy to improve the lives of Georgians. Nothing written here is to be construed as necessarily reflecting the view of the Georgia Public Policy Foundation or as an attempt to aid or hinder the passage of any bill before the U.S. Congress or the Georgia Legislature.

© Georgia Public Policy Foundation (August 12, 2016). Permission to reprint in whole or in part is hereby granted, provided the author and her affiliations are cited.